When is a hazard not a hazard? Or, the issue of failed precautions

… their appearance and their work was as it were a wheel within a wheel. (Ezekiel 1:16)

“It’s turtles all the way down!” (Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time)

R2A consults to a wide range of industries. We advise our clients on topics as diverse as safely emptying a 40-metre-tall sugar silo, procuring a fleet of new Melbourne trams, appropriate decision-making for road tunnel fire emergency response, and corporate governance for electricity industry regulators.

This wonderful diversity of projects lets us take good ideas from one sphere to another, helping our clients implement existing approaches in new contexts to solve known problems. It also shows us recurring problems in risk management approaches. One of the most common is identified hazards not really being hazards.

Formal risk management was introduced to Australia in the 1970s. A pattern then emerged in how organisations often appointed their risk managers. Rather than embarking on a specific ‘risk management’ career path, senior ‘chain-of-command’ managers initially took on risk management responsibilities for their role. As their interest or aptitude developed they increased their risk management portfolio, eventually stepping out of the chain and into the wide-ranging advisory ‘risk manager’ role.

These risk managers have a wide variety of backgrounds, allowing for incredible cross-pollination of their approaches, ideas and techniques as they move between organisations and industries. However, this also leads to an incredible mix of language around risk management concepts. One of the most persistent issues arising from this is the idea that a failed precaution constitutes a hazard.

This issue often appears in the form of concern about following Australian standards. In a design project, for instance, a risk assessment will often identify the risk of not following relevant design standards. But design standards are, without exception, developed to address risks, safety or otherwise. That is, they are a precaution. More precautions must then be added to address this new risk, but each of these introduces a risk if they fail and require still more precautions, and so on ad infinitum – wheels within wheels within wheels, turtles all the way down.

This confusion is promulgated by the Australian risk management standard AS31000 (and its predecessor AS4360), Section 5.5.2 of which notes that “a significant risk can be the failure or ineffectiveness of the risk treatment measures” (i.e. precautions).

Taken in context, this sentence aims to support AS31000’s entirely appropriate focus on monitoring precautions to ensure they remain effective after implementation. In practice however, it further entrenches the idea that failed precautions are, in and of themselves, risks.

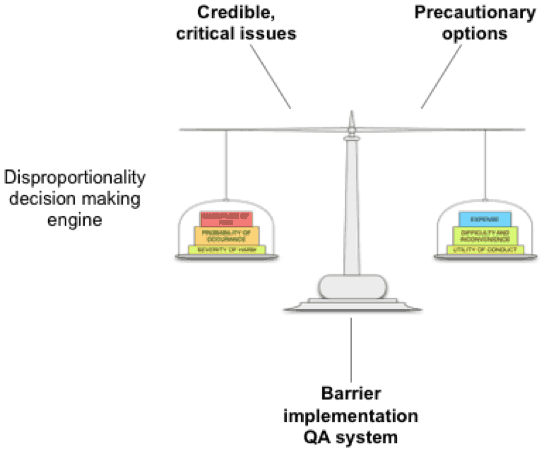

R2A’s ‘Y’ model addresses the problems of this infinite regression by recognising that the monitoring processes which are used to maintain effective precautions form an organisation’s quality assurance/quality control (QA) system.

R2A’s ‘Y’ model

When viewed in this manner, risk management keeps its focus on key precautions for critical issues. The organisation’s QA system (which is generally already established) thus becomes a key element of diligent risk management, rather than a checkbox exercise. This also avoids the need to continuously add lines to a corporate risk register when dealing with a single risk.

We find that this approach not only simplifies the decision-making process as to what precautions are reasonable, it also ensures that risk decisions reported up to senior decision-makers and Boards are clear and concise.

Risk decisions being easier to make and more easily explicable indicates that they will be more easily defended if a risk manifests. We have found our clients to be unanimously in favour of this.

To find out more about R2A’s ‘Y’ model and our wider approach, have a look at the resources on our website, come to one of our EEA Engineering Due Diligence short courses, or purchase the R2A text.