Precautionary Principle vs Precautionary Approach: What's the Difference?

One of the more interesting philosophical issues arising from the introduction of the model WHS legislation is the question of whether the precautionary principle incorporated in environmental legislation is congruent with the precautionary approach of the model WHS legislation.The precautionary principle is typically articulated as: If there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation[1], with due diligence being recognised as a defence in the Victorian Act (Section 66B).The words in Australian legislation are derived from the 1992 Rio Declaration. This formulation is usually recognised as being ultimately derived from the 1980s German environmental policy. The origin of the principle is generally ascribed to the German notion of Vorsorgeprinzip, literally, the principle of foresight and planning[2].The WHS legislation adopts a precautionary approach. It basically requires that all possible practicable precautions for a particular safety issue be identified, and then those that are considered reasonable in the circumstances are to be adopted. In a very real sense is develops the principle of reciprocity as articulated by Lord Atkin[3] in Donoghue vs Stevenson following the Christian articulation, quote: The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer's question "Who is my neighbour?" receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbor. Interestingly, in describing what constitutes a due diligence defence under the WHS act, Barry Sherriff and Michael Tooma[4] favourably quote a case from the Land and Environment Court in NSW, suggesting that due diligence as a defence under WHS law parallels due diligence as a defence under environmental legislation.Does this mean that the two precautionary approaches, despite having quite divergent developmental paths have converged?Tentatively, the answer seems to be ‘Yes’. The common element appears to be the concern with uncertainty stemming from the potential limitations of scientific knowledge to describe comprehensively and predict accurately threats to human safety, and the environment.What does this mean? At the least is means that due diligence as a defence against things that can go wrong in Australia is on the up and up.

[1] Victorian Environment Protection Act 1970. No. 8056 of 1970 Version incorporating amendments as at 1 September 2007. Version No. 161.[2] Jacqueline Peel (2005). The Precautionary Principle in Practice. Environmental Decision Making and Scientific Uncertainty. The Federation Press.[3] Donoghue v. Stevenson (1932). See http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKHL/1932/100.html[4] Barry Sherriff and Michael Tooma (2010). Understanding the Model Work Health and Safety Act. See p 43. State Pollution Control Commission v RV Kelly (1991).

Demonstrating Societal Due Diligence Using the Precautionary Approach

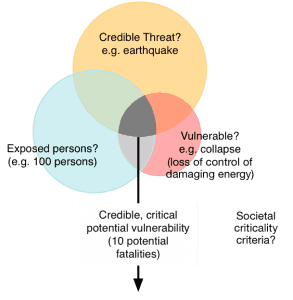

Arising from correspondence and discussion regarding earthquakes in New Zealand and bushfires in Victoria, R2A has been considering the possible application of the precautionary approach from a government regulatory perspective. The Venn diagram below is one result.

Arising from correspondence and discussion regarding earthquakes in New Zealand and bushfires in Victoria, R2A has been considering the possible application of the precautionary approach from a government regulatory perspective. The Venn diagram below is one result.

This implies three primary control options: eliminate the threat, remove exposed persons, or reduce the vulnerability. All are viable options with different perspectives but typically fall into different ‘control’ domains. For example, the ‘exposed persons’ issue is usually a land use planning matter generally being the responsibility of local government. The issue of vulnerability is usually an engineering concern the responsibility for which mostly falls to owners of exposed facilities. The nature of the threat is more a scientific matter and typically the concern of research organisations.

This makes the grey intersection a complex disciplinary patch, with overlapping responsibilities for government agencies, research and engineering organisations and with all the confusions as to whether the ‘hazard’ is a personal problem and the responsibility of individual owners, or a societal problem to be addressed with community resources.

Perhaps the most useful observation from this model to date is that the elimination of persons from an exposed area, a quite natural government response, is only one of three possibilities. The model above suggests that the optimal societal course of action is likely to be a mixture of the three control domains.