Simplifying Hierarchy of Control for Due Diligence

The hierarchy of control is one of those central ideas that safety regulators have been using forever. But it is also one of those very simple ideas that has caused enormous confusion in due diligence.

In hierarchical control terms, the WHS legislation (or OHS in Victoria) provides for two levels of risk control: elimination so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP), and if this cannot be achieved, minimisation SFAIRP.

In addition, criminal manslaughter provisions have been enacted in many jurisdictions.

The post-event test for this will be the common law test albeit to the statutory beyond reasonable doubt criteria.

For example, from WorkSafe Victoria:

The test is based on the existing common law test for criminal negligence in Victoria, and is an appropriately high standard considering the significant penalties for the new offence.

https://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/victorias-new-workplace-manslaughter-offences

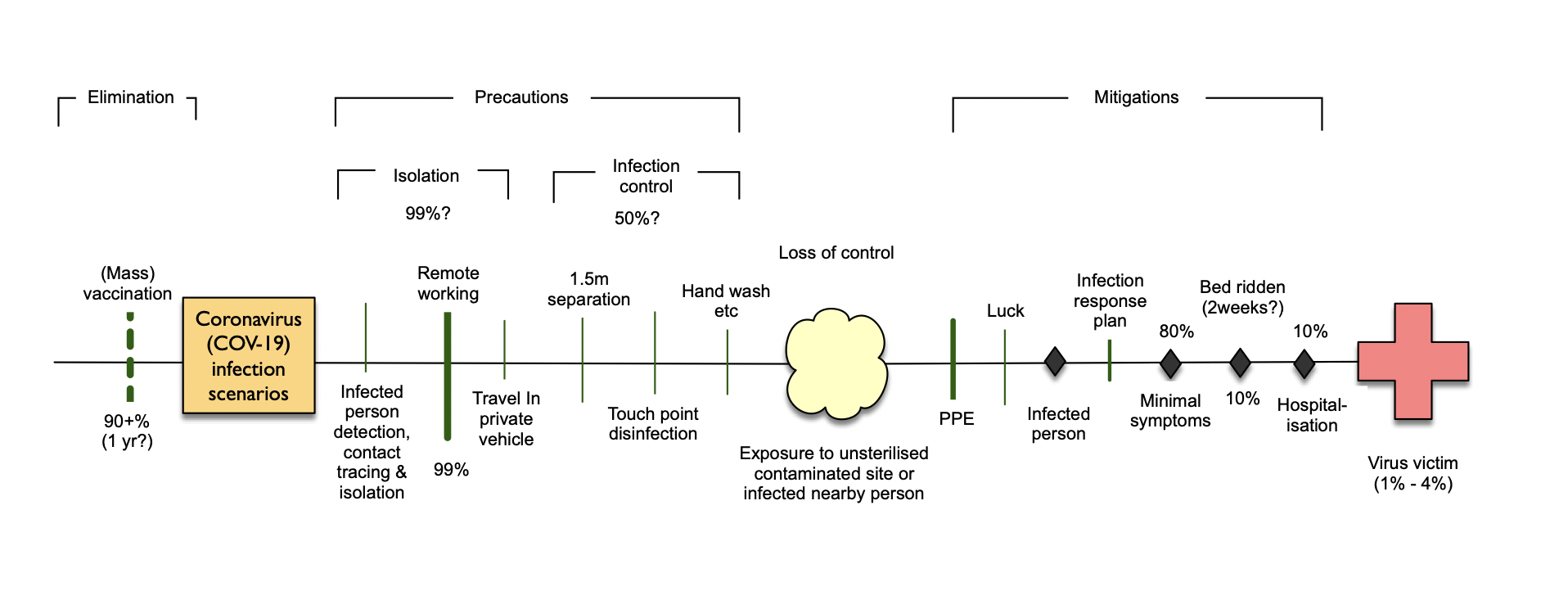

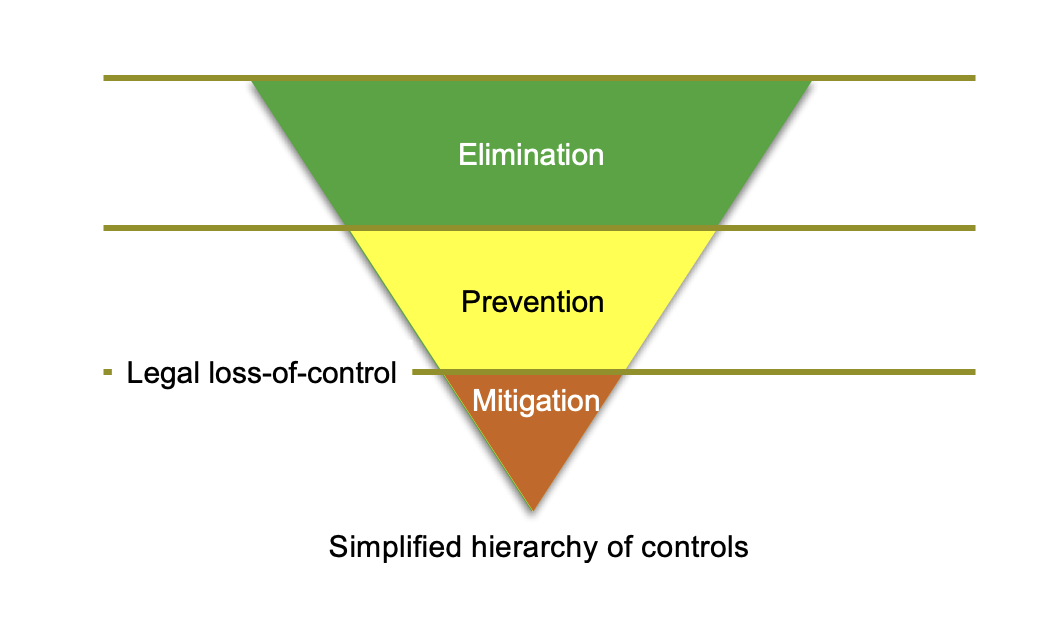

Post-event in court, from R2A’s experience acting as expert witnesses, there are three levels in the hierarchy of control:

- Elimination,

- Prevention, and

- Mitigation.

In causation terms most simply shown as single line threat-barrier diagrams such as the one for Covid 19 below.

Our collective safety regulators have other views. For example, the 2015 Code of Practice (How to Manage Work Health and Safety Risks) which has been adopted by ComCare and NSW has 3 levels of control measures whereas many other jurisdictions adopt the 6-level system like Western Australia. Victoria has a 4-level system.

This inconsistency between jurisdictions seriously undermines the whole idea of harmonised safety legislation. And it also muddles optimal SFAIRP control outcomes. For example, engineering can be an elimination option, as in removing a navigation hazard, a preventative control as in machine guarding, or a mitigation as in an airbag in a car.

In R2A’s view, which we have tested with very many lawyers, the judicial formulation shown below is the only hierarchy of control capable of surviving legal scrutiny and R2A’s preferred approach.

Contact the team at R2A Due Diligence for further advice on hierarchy of controls for due diligence.

SFAIRP not equivalent to ALARP

The idea that SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable) is not equivalent to ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) was discussed in Richard Robinson’s article in the January 2014 edition of Engineers Australia Magazine generates commentary to the effect that major organisations like Standards Australia, NOPSEMA and the UK Health & Safety Executive say that it is. The following review considers each briefly. This is an extract from the 2014 update of the R2A Text (Section 15.3).

The idea that SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable) is not equivalent to ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) was originally discussed in Richard Robinson’s article in the January 2014 edition of Engineers Australia Magazine. At the time, it generated much commentary to the effect that major organisations like Standards Australia, NOPSEMA and the UK Health & Safety Executive say that it is.

Fast forward to 2022 and this is still the case.

The following review considers each briefly. This is an extract from the 2022 update of the R2A Text Engineering Due Diligence – How To Demonstrate SFAIRP (Section 19.3).

The UK HSE’s document, ALARP “at a glance”1 notes:

“You may come across it as SFAIRP (“so far as is reasonably practicable”) or ALARP (“as low as reasonably practicable”). SFAIRP is the term most often used in the Health and Safety at Work etc Act and in Regulations. ALARP is the term used by risk specialists, and duty-holders are more likely to know it. We use ALARP in this guidance. In HSE’s view, the two terms are interchangeable except if you are drafting formal legal documents when you must use the correct legal phrase.”

R2A’s view is that the prudent approach is to always use the correct legal term in the way the courts apply it, irrespective of what a regulator says to the contrary.

NOPSEMA are quite clearly focussed on the precautionary approach to risk. Their briefing paper on ALARP2 indicates in the Core Concepts that:

“Many of the requirements are qualified by the phrase “reduce the risks to a level that is as low as reasonably practicable”. This means that the operator has to show, through reasoned and supported arguments, that there are no other practical measures that could reasonably be taken to reduce risks further.” (Bolding by R2A).

That is, NOPSEMA wish to ensure that all reasonable practicable precautions are in place which is the SFAIRP concept. Indeed, later in Section 8, Good practice and reasonable practicability, there is a discussion concerning the legal, court driven approach to risk. Whilst ALARP is mostly used elsewhere in the document, here NOPSEMA notes:

“When reviewing health or safety control measures for an existing facility, plant, installation or for a particular situation (such as when considering retrofitting, safety reviews or upgrades), operators should compare existing measures against current good practice. The good practice measures should be adopted so far as is reasonably practicable. It might not be reasonably practicable to apply retrospectively to existing plant, for example, all the good practice expected for new plant. However, there may still be ways to reduce the risk e.g. by partial solutions, alternative measures, etc.” (Bolding by R2A).

Standards Australia seems to be severely conflicted in this area in many standards, some of which are called up by statute. For example, the Power System Earthing Guide presents huge difficulties.

Another example is AS 5577 – 2013 Electricity network safety management systems. Section 1.2 Fundamental Principles point (e): which requires life cycle SFAIRP for risk elimination and ALARP for risk management:

Hazards associated with the design, construction, commissioning, operation, maintenance and decommissioning of electrical networks are identified, recorded, assessed and managed by eliminating safety risks so far as is reasonably practicable, and if it is not reasonably practicable to do so, by reducing those risks to as low as reasonably practicable. (Bolding by R2A).

It seems that Standards Australia simply do not see that there is a difference. The terms appear to be used interchangeably.

Safe Work Australia is only SFAIRP3. There does not appear to be any confusion whatsoever. For example, the Interpretative Guideline – Model Work Health and Safety Act The Meaning of ‘Reasonably Practicable’ indicates:

“What is ‘reasonably practicable’ is determined objectively. This means that a duty-holder must meet the standard of behaviour expected of a reasonable person in the duty-holder’s position and who is required to comply with the same duty.

“There are two elements to what is ‘reasonably practicable’. A duty-holder must first consider what can be done - that is, what is possible in the circumstances for ensuring health and safety. They must then consider whether it is reasonable, in the circumstances to do all that is possible.

“This means that what can be done should be done unless it is reasonable in the circumstances for the duty-holder to do something less.

“This approach is consistent with the objects of the WHS Act which include the aim of ensuring that workers and others are provided with the highest level of protection that is reasonably practicable.”

ALARP is simply not mentioned, anywhere.

Although the ALARP verses SFAIRP debate continues in many places and the current position of many is that SFAIRP equals ALARP; nothing could be further from the truth.

For engineers, the meaning is in the method; results are only consequences.

SFAIRP represents a fundamental paradigm shift in engineering philosophy and the way engineers are required to conduct their affairs.

It represents a drastically different way of dealing with future uncertainty.

It represents the move from the limited hazard, risk and ALARP analysis approach to the more general designers’ criticality, precaution and SFAIRP approach.

That is;

From: Is the problem bad enough that we need to do something about it?

To: Here’s a good idea to deal with a critical issue, why wouldn’t we do it?

SFAIRP is paramount in Australian WHS legislation and has flowed into Rail and Marine Safety National law, amongst others.

In Victoria, SFAIRP has now also been incorporated into Environmental legislation.

Apart from the fact that SFAIRP is absolutely endemic in Australian legislation with manslaughter provisions to support it proceeding apace, SFAIRP is just a better way to live.

It presents a positive, outcome driven design approach, always testing for anything else that can be done rather than trusting an unrepeatable (and therefore unscientific) estimation of rarity for why you wouldn’t.

If you'd like to learn more about SFAIRP for Engineering Due Diligence, you may be interested in purchasing our textbook. If you'd like to discuss how R2A can help your organisation, fill out our contact form and we'll be in touch.

Editor's note: This article was originally published on 22 January 2014 and has been updated for accuracy and comprehensiveness.

1 https://www.hse.gov.uk/managing/theory/alarpglance.htm viewed 21 February 2022

2 https://www.nopsema.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021-03/A138249.pdf viewed 21 February 2022

3https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/2002/guide_reasonably_practicable.pdf viewed 21 February 2022

Why Due Diligence is now a 'Categorical Imperative'

WA adopts WHS legislation with criminal manslaughter provisions

NZ charges 13 under HSWA over White Island eruption that killed 22

The adoption of the model WHS legislation in Australasia is now practically complete with the passing of the act by the Western Australian parliament. Whilst yet to be proclaimed, the WA version includes criminal manslaughter provisions with a maximum penalty of 20 years for individuals.

Victoria is now formally the only state not to have adopted the model WHS Act, although this is practically inconsequential, as the due diligence concept to demonstrate SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable) is embodied in the 2004 OHS Act, and the criminal manslaughter provisions of same commenced on the 1st of July this year.

New Zealand adopted the model WHS legislation in the form of the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015. Judging by the number of commissions R2A has had in NZ in 2020, it has come as a bit of a surprise to many, particularly to those using the hazard-based approach of target levels of risk and safety such as ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable), that these have been completed superseded by the new legislation and cannot demonstrate safety due diligence.

New Zealand has not presently adopted the criminal manslaughter provisions being introduced into Australia, but it did include the significant penalties for recklessness (knew or made or let it happen) with up to 5 years jail for individuals.

In all Australasian jurisdictions, regulators appear prosecutorially active with a number of cases presently under investigation and before the courts. For example, the White Island volcano incident in New Zealand which killed 22. Ten parties and 3 individuals have been charged.

Perhaps what has surprised many in NZ is the observation by NZ Worksafe, that for critical (kill or maim) hazards like volcanic eruptions, it only has to be reasonably foreseeable, not actually have happened before. That is, the fact that the hazard has not occurred before is not sufficient to warrant not thinking about it any further.

All in all, due diligence has become endemic, to the point that it has become, in the philosopher Immanuel Kant’s terms, a categorical imperative.

That is, our parliamentarians and judges seem to have decided that due diligence is universal in its application and creates a moral justification for action. This also means the converse, that failure to act demands sanction against the failed decision maker, which is being increasingly tested in our courts.

Australia’s Bushfires from a Due Diligence Perspective

Like you, we have been devastated by the recent bushfire events in Victoria, NSW and Queensland. We hope you have been able to stay safe and have not been directly affected. Richard and I have been reflecting on bushfires in history and if there are any key take away messages from a due diligence perspective.

Richard’s involvement with bushfire risk reviews commenced in the 1980s following the Ash Wednesday fires in Victoria. As part of a research project, Richard completed a threat and vulnerability assessment to see if there were any precautions that were missing from (then) current practices.

The outcome was that there were significant risk reduction benefits associated with improved town planning. This required the placement of huge fire breaks, such as golf courses and potato fields to the north and west of the town.

From the CFA website:

A change in wind direction is one of the most dangerous influences on fire behaviour. Many people who die in bushfires get caught during or after a wind change.

In Victoria, hot, dry winds typically come from the north and northwest and are often followed by a southwest wind change. In this situation the side of the fire can quickly become a much larger fire front.

Richard was then a member of the Powerline Bushfire Safety Taskforce that followed the Black Saturday fires in 2009.

My involvement continues on the Powerline Bushfire Safety Committee.

One of the key findings of the Black Saturday Royal Commission was that the majority of the fires were started by electrical assets and significantly contributed to the huge number of fatalities.

I am very proud to be involved in the roll out of REFCLs (Rapid Earth Fault Current Limiter) in Victoria, and their contribution to improving bushfire safety. Data from a total fire ban day in November 2019, revealed that REFCLs on the electrical network are working to reduce the number of fire starts from electrical assets.

Although bushfires of this magnitude were a new occurrence for NSW in 2019/20, there are many learnings from past Victorian fires that can be applied.

And, it is interesting to compare the community’s response to cyclones in the north of Australia to community responses in bushfire prone areas.

Buildings in cyclone prone areas are subject to more stringent building codes and during cyclone warning periods. It’s typically practice for people living in those areas to go home and prepare their house. All loose items of furniture are removed or tied down, shutters are closed, and communities are generally shutdown.

The same does not occur for bushfires prone areas.

As due diligence engineers we ask the question is there anything more that can be done?

The focus should always be on precautions rather than mitigations and we should certainly learn from past experiences.

In light of these recent events, we have revisited our Safety Due Diligence White Paper and Powerline Bushfire Safety Taskforce Case Study. We hope you find them interesting and insightful.

Why the philosophy of compliance will always fail

A very popular pastime of Australian parliaments is to pass legislation and regulation on the basis that, once it becomes the law, everyone will comply and it will, therefore, be effective.A concomitant result is that many boards and their legal advisers conduct compliance audits to confirm that these legal obligations have been met and, having done so, declare that they are ethically robust, safe and societally responsible.This is a flawed philosophy at many levels.

-

First, the sheer number and extent of laws and regulations in Australia means that the actual possibility of demonstrating compliance with each and every one is a logical impossibility.

Conceptually, the philosophy of compliance suggests that the more laws and regulations the better, even if the cost to demonstrate compliance continues to increase.

-

Second, in safety terms, mere compliance can never make anything safe.

It is simply not possible for our parliaments and regulators to predict in advance all the possible existing concerns, let alone the circumstances of possible future problems.The objective should be to understand the purpose of something and to meet that need. Compliance is a secondary aspect.For a simple example: Pool fencing is designed to prevent children drowning, not to satisfy a building surveyor, although this may be necessary to satisfy society that it has been done properly.

-

Third, compliance has always been about ensuring minimums; controlling the worst excesses.

It is seldom about promoting the best that we-can-do.The behaviour of the financial sector, the sex scandals in religious orders and the mistreatment in aged care are cases in point. From a societal viewpoint, the horrendous matters reported in the various Royal Commissions simply ought not to have happened.But, will increased legislation and regulation prevent such dreadful things from re-occurring in the future? Or is there a better way?

Interestingly, the engineers seem to have always understood this.

The Code of Ethics of Engineers Australia has always emphasised that the interest of society comes before sectional interests.These basic understandings, as articulated, for example, by the managing director of a major Australian Consulting Engineering firm to a young engineer in the 1970s, include:

1. S/he who pays you is your client.

A simple rule. Often overlooked. Having a building certifiers paid for by the developer easily leads to lazy certification. A better approach would be to have the (future) owners pay for the certification. The possibility of a conflict of interest would be functionally reduced by design.

2. No kickbacks.

A lot or rules and regulations can be written about this. But if a professional adviser does not understand that a hidden commission is morally indefensible, there is a problem that no amount of regulation can fix. It may not be illegal to pay a spotter’s fee, but it’s certainly morally suspect.

3. Stick to your area of competence.

Don’t provide advice or opinions without adequate knowledge. Does this really need legislation and regulation?

4. Be responsible for your own negligence.

That is, recognise that you can’t always be right. Amongst other things, advisers need professional indemnity insurance, in part, to remedy honest mistakes.

5. Give credit where credit is due.

That is, don’t take credit for what others have achieved.

There is nothing new or novel about these basic understandings. But rather than legislating and regulating with a list of things not-to-do, it may be better to re-design the commercial environment so that virtuous behaviour is rewarded.Certainly, the old ACEA (Association of Consulting Engineers, Australia) used to do this. ACEA required that member firms were controlled by directors who were bound by the Engineers’ Code of Ethics.This meant that in the event of a decision between the best interests of the consulting firm and the client’s, the client’s interests normally held sway.

What are the Unintended Consequences of Due Diligence?

In my article Why Risk changed to Due Diligence & Why it’s become so Important, I briefly described the principle of; do unto others, otherwise known as the Principle of Reciprocity, and how Governments in Australia have incorporated the concept in legislation in the form of due diligence. With this in mind, it’s important to consider the unintended consequences of due diligence.

Below I examine two examples of the logical consequence set of the due diligence approach.

Unlicensed persons doing electrical work

Due diligence in safety legislation requires that risks be eliminated, so far as is reasonably practical, or if they can't be eliminated, reduced so far as is reasonably practical.The bane of electrical regulators in Australia is the home handyman working in a roof space and fiddling with the 240V conductors. Death is a regular result. The fatalities arising from the home insulation Royal Commission also spring to mind.Most of us have been replacing dichroic downlights in our existing houses with energy efficient 12V LEDs. And although it may be unreasonable to retrospectively replace the 240V wiring in the roof space with extra low voltage (ELV) conductors for existing structures, it is obviously quite achievable for new dwellings. And if all the wiring in the roof is 12 or 24 V (and all the 240V wiring is in the walls) then the possibility of being electrocuted in a roof space is pretty much eliminated, which is the purpose of the legislation. In fact, the most likely thing to happen next is that all lights will get smart and be provided with power over Ethernet (PoE) (up to 48V).What all this means is that, in the event of an electrocution in a roof space, the designer of domestic dwellings that did not install ELV lighting in houses built since the commencement of the WHS legislation will, most likely be considered reckless in terms of the legislation since the elimination option is obviously reasonably practicable.

Global warming & the City of Melbourne

Does the Parliament of Victoria have a duty of care to Melbournians? Not just current, but future ones? The High Court of Australia has been clear that future generations (yet unborn) can be considered neighbours for the purposes of having a duty of care.If that's the case, when it comes to global warming (whether it's real or not is an interesting question but it's certainly credible) if the Greenland ice sheet melts, which is arguably what will happen if temperatures increase by two or three degrees, the sea level in Port Phillip Bay will rise about seven meters.Seven meters in a low-lying city like Melbourne would be significant. You could forget Flinders Street Station as your meeting point.Due diligence is all about options analysis for credible (foreseeable) hazards and I can tell you of at least three, just from a preliminary internet search.

- NASA wants to put in space sun shields and actually shield the planet from the sun. This option is in the $trillions, probably, but quite do-able.

- Cambridge University engineers want to increase earthshine by squirting vapor at high altitude increasing the cloud cover and, thereby, reflecting more energy away from the planet, which is entirely practical. This would probably cost $20B or so to cool the planet.

- The cheapest option is one which an American decided to try by taking a ship load of fertilizers out to sea and dumping it into the ocean to see what would happen. The result was a plankton bloom.Applying this idea in the Southern Ocean, you would get lots of plankton, and then lots of krill, and consequently, fat whales. But much of the plankton and krill would die before being consumed and sink to the Antarctic ocean floor thereby creating a giant carbon sink. To cool the planet (and de-acidify the oceans as well) will be less than probably $10B or so based on the last estimate I’ve seen.

The Victorian desalination plant cost over $5B and ultimately $18B or so all up during the 27 year lifetime of the plant. It was built to deal with the credible, critical threat of Melbourne running out of water if a 10 year drought persisted.All this means that the Government of Victoria has the resources to implement at least one of the options described above. And following its own legislation, it seems the government has committed itself to seriously considering if it should cool the planet to protect the citizens of Melbourne against flooding due to the credible possibility of global warming.These examples, along with many more, along with the tools we use to engineer due diligence, are detailed in our Due Diligence Engineering textbook that’s available to purchase here.If you’d like our assistance with any upcoming due diligence, contact us for a friendly chat.

Why Risk changed to Due Diligence & Why it’s become so Important

At our April launch of the 11th Edition of Engineering Due Diligence textbook, I discussed how the service of Risk Reviews has changed to Due Diligence and why it’s become so important for Australian organisations.

But to start, I need to go back to 1996. The R2A team and I were conducting risk reviews on large scale engineering projects, such as double deck suburban trains and traction interlocking in NSW, and why the power lines in Tasmania didn't need to comply with CB1 & AS7000, and why the risk management standard didn't work in these situations.And, what we kept finding was that as engineers we talked about high consequence, low likelihood (rare) events, and then we’d argue the case with the financial people over the cost of precautions we suggested should be in place, we’d always lose the argument.However, when lawyers were standing with us saying, 'what the engineers are saying makes sense - it's a good idea', then the ‘force’ was with us and what we as engineers suggested was done.

As a result, in the 2000s we started flipping the process around and would lead with the legal argument first and then support this with the engineering argument. And every time we did that, we won.

It was at this stage we started changing from Risk and Reliability to Due Diligence Engineers, because it was always necessary to run with the due diligence first to make our case.

Since we made this fundamental change in service and became more involved in delivering high level work, that is, due diligence, it has also become part of the Australian governance framework.Due diligence has become endemic in Australian legislation. In corporations’ law; directors must demonstrate diligence to ensure, for example, that a business pays its bills when they fall due. It's in WHS Legislation. It's in Environmental Legislation. Due diligence is now required to demonstrate good corporate governance.And what I mean by that is that there’s a swirl of ideas that run around our parliaments. Our politicians pick the ideas they think are good ones. One of these was the notion of due diligence that was picked up from the judicial, case (common) law system.There’s an interesting legal case on the topic going back to 1932: Donoghue vs Stevenson; the Snail in the Bottle. When making his decision, the Brisbane-born English law lord, Lord Aitken said that the principle to adopt is; do unto others as you would have done unto you.The do unto others principle (the principle of reciprocity) was nothing new; it’s been a part of major philosophies and religions for over 2000 years.Our parliamentarians took the do unto others idea and incorporated it into Acts, Regulations and Codes of Practice as the notion of Due Diligence.That is, due diligence has become endemic in Australian legislation and in case law, to the point that it has become, in the philosopher Immanuel Kant’s terms, a categorical imperative. That is, our parliamentarians and judges seem to have decided that due diligence is universal in its application and creates a moral justification for action. This also means the converse, that failure to act demands sanction against the failed decision maker. I discuss this further along with two examples in the article What are the Unintended Consequences of Due Diligence.To learn more about Engineering Due Diligence and the tools we teach at our two-day workshop, you can purchase our text resource here.If you’d like to discuss we can help you make diligent decisions that are safe, effective and compliant, we’d love to hear from you. Contact us today.

Worse Case Scenario versus Risk & Combustible Cladding on Buildings

BackgroundThe start of 2019 has seen much media attention to various incidents resulting from, arguably, negligent decision making.One such incident was the recent high-rise apartment building fire in Melbourne that resulted in hundreds of residents evacuated.The fire is believed to have started due to a discarded cigarette on a balcony and quickly spread five storeys. The Melbourne Fire Brigade said it was due to the building’s non-combustible cladding exterior that allowed the fire to spread upwards. The spokesperson also stated the cladding should not have been permitted as buildings higher than three storeys required a non-combustible exterior.Yet, the Victorian Building Authority did inspect and approve the building.Similar combustible cladding material was also responsible for another Melbourne based (Docklands) apartment building fire in 2014 and for the devastating Grenfell Tower fire in London in 2017 that killed 72 people with another 70 injured.This cladding material (and similar) is wide-spread across high-rise buildings across Australia. Following the Docklands’ building fire, a Victorian Cladding Task Force was established to investigate and address the use of non-compliant building materials on Victorian buildings.Is considering Worse Case Scenario versus Risk appropriate?In a television interview discussing the most recent incident, a spokesperson representing Owners’ Corporations stated owners needed to look at worse case scenarios versus risk. He followed the statement with “no one actually died”.While we agree risk doesn’t work for high consequence, low likelihood events, responsible persons need to demonstrate due diligence for the management of credible critical issues.The full suite of precautions needs to be looked at for a due diligence argument following the hierarchy of controls.The fact that no one died in either of the Melbourne fires can be attributed to Australia’s mandatory requirement of sprinklers in high rise buildings. This means the fires didn’t penetrate the building. However, the elimination of cladding still needs to be tested from a due diligence perspective consistent with the requirements of Victoria’s OHS legislation.What happens now?The big question, beyond that of safety, is whether the onus to fix the problem and remove / replace the cladding is now on owners at their cost or will the legal system find construction companies liable due to not demonstrating due diligence as part of a safety in design process?Residents of the Docklands’ high-rise building decided to take the builder, surveyor, architect, fire engineers and other consultants to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) after being told they were liable for the flammable cladding.Defence for the builder centred around evidence of how prevalent the cladding is within Australian high-rise buildings.The architect’s defence was they simply designed the building.The surveyor passed the blame onto the Owners’ Corporation for lack of inspections of balconies (where the fire started, like the most recent fire, with a discarded cigarette).Last week (at the time of writing), the apartment owners were awarded damages for replacement of the cladding, property damages from the fire and an increase in insurance premiums due to risk of future incidents. In turn, the architect, fire engineer and building surveyor have been ordered to reimburse the builder most of the costs.Findings by the judge included the architect not resolving issues in design that allowed extensive use of the cladding, a failure of “due care” by the building surveyor in its issue of building permit, and failure of fire engineer to warn the builder the proposed cladding did not comply with Australian building standards.Three percent of costs were attributed to the resident who started the fire.Does this ruling set precedence?Whilst other Owners’ Corporations may see this ruling as an opportunity (or back up) to resolve their non-compliant cladding issues, the Judge stated they should not see it as setting any precedent.

"Many of my findings have been informed by the particular contracts between the parties in this case and by events occurring in the course of the Lacrosse project that may or may not be duplicated in other building projects," said Judge Woodward.

If you'd like to discuss how conducting due diligence from an engineering perspective helps make diligent decisions that are effective, safe and compliant, contact us for a chat.

Why your team has a duty of care to show they've been duly diligent

In October and November (2018), I presented due diligence concepts at four conferences: The Chemeca Conference in Queenstown, the ISPO (International Standard for maritime Pilot Organizations) conference in Brisbane, the Australian Airports Association conference in Brisbane (with Phil Shaw of Avisure) and the NZ Maritime Pilots conference in Wellington.

The last had the greatest representation of overseas presenters. In particular, Antonio Di Lieto, a senior instructor at CSMART, Carnival Corporation's Cruise ship simulation centre in the Netherlands. He mentioned that:

a recent judgment in Italian courts had reinforced the paramountcy of the due diligence approach but in this instance within the civil law, inquisitorial legal system.

This is something of a surprise. R2A has previously attempted to test ‘due diligence’ in the European civil (inquisitorial) legal system over a long period by presenting papers at various conferences in Europe. The result was usually silence or some comment about the English common law peculiarities.

The aftermath of the accident at the port of Genoa. Credit: PA

The incident in question occurred on May 2013. While executing the manoeuvre to exit the port of Genoa, the engine of the cargo ship “Jolly Nero” went dead. The big ship smashed into the Control Tower, destroying it, and causing the death of nine people and injuring four.

So far the ship’s master, first officer and chief engineer have all received substantial jail terms, as has the Genoa port pilot. It seems that a failure to demonstrate due diligence secured these convictions

And there are two more ongoing inquiries:

- One regards the construction of the Tower in that particular location, an investigation that has already produced two indictments; and

- The second that focuses on certain naval inspectors that certified ship.

It's important to realise everyone involved -- the bridge crew, the ship’s engineer, ship certifier, marine pilot, and the port designer -- all have a duty of care that requires, post event, they had been duly diligent.

Are you confident in your team's diligent decision making? If not, R2A can help; contact us to discuss how.

Australian Standard 2885, Pipeline Safety & Recognised Good Practice

Australian guidance for gas and liquid petroleum pipeline design guidance comes, to a large extent, from Australian Standard 2885. Amongst other things AS2885 Pipelines – Gas and liquid petroleum sets out a method for ensuring these pipelines are designed to be safe.

Like many technical standards, AS2885 provides extensive and detailed instruction on its subject matter. Together, its six sub-titles (AS2885.0 through to AS2885.5) total over 700 pages. AS2885.6:2017 Pipeline Safety Management is currently in draft and will likely increase this number.

In addition, the AS2885 suite refers to dozens of other Australian Standards for specific matters.

In this manner, Standards Australia forms a self-referring ecosystem.

R2A understands that this is done as a matter of policy. There are good technical and business reasons for this approach;

- First, some quality assurance of content and minimising repetition of content, and

- Second, to keep intellectual property and revenue in-house.

However, this hall of mirrors can lead to initially small issues propagating through the ecosystem.

At this point, it is worth asking what a standard actually is.

In short, a standard is a documented assembly of recognised good practice.

What is recognised good practice?

Measures which are demonstrably reasonable by virtue of others spending their resources on them in similar situations. That is, to address similar risks.

But note: the ideas contained in the standard are the good practice, not the standard itself.

And what are standards for?

Standards have a number of aims. Two of the most important being to:

- Help people to make decisions, and

- Help people to not make decisions.

That is, standards help people predict and manage the future – people such as engineers, designers, builders, and manufacturers.

When helping people not make decisions, standards provide standard requirements, for example for design parameters. These standards have already made decisions so they don’t need to be made again (for example, the material and strength of a pipe necessary for a certain operating pressure). These are one type of standard.

The other type of standard helps people make decisions. They provide standardised decision-making processes for applications, including asset management, risk management, quality assurance and so on.

Such decision-making processes are not exclusive to Australian Standards.

One of the more important of these is the process to demonstrate due diligence in decision-making – that is that all reasonable steps were taken to prevent adverse outcomes.

This process is of particular relevance to engineers, designers, builders, manufacturers etc., as adverse events can often result in safety consequences.

A diligent safety decision-making process involves,:

- First, an argument as to why no credible, critical issues have been overlooked,

- Second, identification of all practicable measures that may be implemented to address identified issues,

- Third, determination of which of these measures are reasonable, and

- Finally, implementation of the reasonable measures.

This addresses the legal obligations of engineers etc. under Australian work health and safety legislation.

Standards fit within this due diligence process as examples of recognised good practice.

They help identify practicable options (the second step) and the help in determining the reasonableness of these measures for the particular issues at hand. Noting the two types of standards above, these measures can be physical or process-based (e.g. decision-making processes).

Each type of standard provides valuable guidance to those referring to it. However the combination of the self-referring standards ecosystem and the two types of standards leads to some perhaps unintended consequences.

Some of these arise in AS2885.

One of the main goals of AS2885 is the safe operation of pipelines containing gas or liquid petroleum; the draft AS2885:2017 presents the standard's latest thinking.

As part of this it sets out the following process.

- Determine if a particular safety threat to a pipeline is credible.

- Then, implement some combination of physical and procedural controls.

- Finally, look at the acceptability of the residual risk as per the process set out in AS31000, the risk management standard, using a risk matrix provided in AS2885.

If the risk is not acceptable, apply more controls until it is and then move on with the project. (See e.g. draft AS2885.6:2017 Appendix B Figures B1 Pipeline Safety Management Process Flowchart and B2 Whole of Life Pipeline Safety Management.)

But compare this to the decision-making process outlined above, the one needed to meet WHS legislation requirements. It is clear that this process has been hijacked at some point – specifically at the point of deciding how safe is safe enough to proceed.

In the WHS-based process, this decision is made when there are no further reasonable control options to implement. In the AS2885 process the decision is made when enough controls are in place that a specified target level of risk is no longer exceeded.

The latter process is problematic when viewed in hindsight. For example, when viewed by a court after a safety incident.

In hindsight the courts (and society) actually don’t care about the level of risk prior to an event, much less whether it met any pre-determined subjective criteria.

They only care whether there were any control options that weren’t in place that reasonably ought to have been.

‘Reasonably’ in this context involves consideration of the magnitude of the risk, and the expense and difficulty of implementing the control options, as well as any competing responsibilities the responsible party may have.

The AS2885 risk sign-off process does not adequately address this. (To read more about the philosophical differences in the due diligence vs. acceptable risk approaches, see here.)

To take an extreme example, a literal reading of the AS2885.6 process implies that it is satisfactory to sign-off on a risk presenting a low but credible chance of a person receiving life-threatening injuries by putting a management plan in place, without testing for any further reasonable precautions.[1]

In this way AS2885 moves away from simply presenting recognised good practice design decisions as part of a diligent decision-making process and, instead, hijacks the decision-making process itself.

In doing so, it mixes recognised good practice design measures (i.e. reasonable decisions already made) with standardised decision-making processes (i.e. the AS31000 risk management approach) in a manner that does not satisfy the requirements of work health and safety legislation. The draft AS2885.6:2017 appears to realise this, noting that “it is not intended that a low or negligible risk rank means that further risk reduction is unnecessary”.

And, of course, people generally don’t behave quite like this when confronted with design safety risks.

If they understand the risk they are facing they usually put precautions in place until they feel comfortable that a credible, critical risk won’t happen on their watch, regardless of that risk’s ‘acceptability’.

That is, they follow the diligent decision-making process (albeit informally).

But, in that case, they are not actually following the standard.

This raises the question:

Is the risk decision-making element of AS2885 recognised good practice?

Our experience suggests it is not, and that while the good practice elements of AS2885 are valuable and must be considered in pipeline design, AS2885’s risk decision-making process should not.

[1] AS2885.6 Section 5: “... the risk associated with a threat is deemed ALARP if ... the residual risk is assessed to be Low or Negligible”

Consequences (Section 3 Table F1): Severe - “Injury or illness requiring hospital treatment”. Major: “One or two fatalities; or several people with life-threatening injuries”. So one person with life-threatening injuries = ‘Severe’?

Likelihood (Section 3 Table 3.2): “Credible”, but “Not anticipated for this pipeline at this location”,

Risk level (Section 3 Table 3.3): “Low”.

Required action (Section 3 Table 3.4): “Determine the management plan for the threat to prevent occurrence and to monitor changes that could affect the classification”.

Risk Engineering Body of Knowledge

Engineers Australia with the support of the Risk Engineering Society have embarked on a project to develop a Risk Engineering Book of Knowledge (REBoK). Register to join the community.

The first REBoK session, delivered by Warren Black, considered the domain of risk and risk engineering in the context risk management generally. It described the commonly available processes and the way they were used.

Following the initial presentation, Warren was joined by R2A Partner, Richard Robinson and Peter Flanagan to answer participant questions. Richard was asked to (again) explain the difference between ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) and SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable).

The difference between ALARP and SFAIRP and due diligence is a topic we have written about a number of times over the years. As there continues to be confusion around the topic, we thought it would be useful to link directly to each of our article topics.

Does ALARP equal due diligence, written August 2012

Does ALARP equal due diligence (expanded), written September 2012

Due Diligence and ALARP: Are they the same?, written October 2012

SFAIRP is not equivalent to ALARP, written January 2014

When does SFAIRP equal ALARP, written February 2016

Future REBoK sessions will examine how the risk process may or may not demonstrate due diligence.

Due diligence is a legal concept, not a scientific or engineering one. But it has become the central determinant of how engineering decisions are judged, particularly in hindsight in court.

It is endemic in Australian law including corporations law (eg don’t trade whilst insolvent), safety law (eg WHS obligations) and environmental legislation as well as being a defence against (professional) negligence in the common law.

From a design viewpoint, viable options to be evaluated must satisfy the laws of nature in a way that satisfies the laws of man. As the processes used by the courts to test such options forensically are logical and systematic and readily understood by engineers, it seems curious that they are not more often used, particularly since it is a vital concern of senior decision makers.

Stay tuned for further details about upcoming sessions. And if you are needing clarification around risk, risk engineering and risk management, contact us for a friendly chat.

Rights vs Responsibilities in Due Diligence

A recent conversation with a consultant to a large law firm described the current legal trend in Melbourne, notably that rights had become more important than responsibilities.This certainly seems to be the case for commercial entities protecting sources of income, as particularly evidenced in the current banking Royal Commission (Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry).It seems that, in the provision of financial advice, protecting consulting advice cash flow was seen as much more important than actually providing the service.Engineers probably have a reverse perspective. As engineers deal with the real (natural material) world, poor advice is often very obvious. When something fails unexpectedly, death and injury are quite likely.Just consider the Grenfell Tower fire in London and the Lacrosse fire in Melbourne. This means that for engineers at least, responsibilities often overshadow rights.This is a long standing, well known issue. For example, the old ACEA (Association of Consulting Engineers, Australia) used to require that at least 50% of the shares of member firms were owned by engineers who were members in good standing of Engineers Australia (FIEAust or MIEAust) and thereby bound by Engineers Australia’s Code of Ethics.The point was to ensure that, in the event of a commission going badly, the majority of the board would abide by the Code of Ethics and look after the interests of the client ahead of the interests of the shareholders.Responsibilities to clients were seen to be more important than shareholder rights, a concept which appears to be central to the notion of trust.

Role & Responsibility of an Expert Witness

Arising from a recent expert witness commission, the legal counsel directed R2A’s attention to Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001} NSWCA 305 (14 September 2001), which provides an excellent review of the role and responsibility of an expert witness, at least in NSW.

Arising from an expert witness commission, relevant counsel has directed R2A’s attention to Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001} NSWCA 305 (14 September 2001), which provides an excellent review of the role and responsibility of an expert witness, at least in NSW. The case cites many authorities outlining these responsibilities. For example, (at 59) it indicates that for the professor’s report to be useful, it is necessary for it to comply with the prime duty of experts in giving opinion evidence, that is, to furnish the trier of fact with criteria enabling evaluation of the validity of the expert’s conclusions. This is alternatively stated in a number of different places and ways, for example (at 60);Courts cannot be expected to act upon opinions the basis of which is unexplained. And again (at 69); Before a court can assess the value of an opinion it must know the facts upon which it is based. If the expert has been misinformed about the facts or has taken irrelevant facts into consideration or has omitted to consider the relevant ones, the opinion will be valueless. In our judgement, counsel calling an expert should in examination in chief ask his witness to state the facts upon which his opinion is based. It is wrong to leave the other side to elicit the facts by cross-examination. In keeping with what constitutes expert witness opinion in the above, it remains a source of frustration to R2A that legal decisions can be so opaque to non-lawyers that it requires legal counsel to direct R2A to the best decisions to provide insight in to the workings of our courts. From R2A’s perspective, judgements should ideally be available in plain English on searchable databases, so that the information is readily available to all. Apart from making the life of due diligence engineers easier, it would also enhance the value of the work of the courts to the society they serve. Interestingly, David Howarth (professor of Cambridge Law and Public Policy) whom R2A sponsored to Melbourne last year (2017), made a passing remark that there was a reason for this complexity. It is to do with the fact that judicial decisions can effectively become retrospective in the common law. To avoid this outcome, judges ensure that the detailed circumstances of each decision is spelt out so that any such retrospectivity can be curtailed. Editor's Note: This article was originally posted on 1 July 2014 and has been updated for accuracy and relevance.

Engineering As Law

Both law and engineering are practical rather than theoretical activities in the sense that their ultimate purpose is to change the state of the world rather than to merely understand it. The lawyers focus on social change whilst the engineers focus on physical change.It is the power to cause change that creates the ethical concerns. Knowing does not have a moral dimension, doing does. Mind you, just because you have the power to do something does not mean it ought to be done but conversely, without the power to do, you cannot choose.Generally for engineers, it must work, be useful and not harm others, that is, fit for purpose. The moral imperative arising form this approach for engineers generally articulated in Australia seems to be:

- S/he who pays you is your client (the employer is the client for employee engineers)

- Stick to your area of competence (don’t ignorantly take unreasonable chances with your client’s or employer’s interests)

- No kickbacks (don’t be corrupt and defraud your client or their customers)

- Be responsible for your own negligence (consulting engineers at least should have professional indemnity insurance)

- Give credit where credit is due (don’t pinch other peoples ideas).

Overall, these represent a restatement of the principle of reciprocity, that is, how you would be expected to be treated in similar circumstances and therefore becomes a statement of moral law as it applies to engineers.

How did it get to this? Project risk versus company liability

Disclosure: Tim Procter worked in Arup’s Melbourne office from 2008 until 2016.Shortly after Christmas a number of media outlets reported that tier one engineering consulting firm Arup had settled a major court case related to traffic forecasting services they provided for planning Brisbane’s Airport Link tunnel tollway. The Airport Link consortium sued Arup in 2014, when traffic volumes seven months after opening were less than 30% of that predicted. Over $2.2b in damages were sought; the settlement is reportedly more than $100m. Numerous other traffic forecasters on major Australian toll road projects have also faced litigation over traffic volumes drastically lower than those predicted prior to road openings.Studies and reviews have proposed various reasons for the large gaps between these predicted and actual traffic volumes on these projects. Suggested factors have included optimism bias by traffic forecasters, pressure by construction consortia for their traffic consultants to present best case scenarios in the consortia’s bids, and perverse incentives for traffic forecasters to increase the likelihood of projects proceeding past the feasibility stage with the goal of further engagements on the project.Of course, some modelling assumptions considered sound might simply turn out to be wrong – however, Arup’s lead traffic forecaster agreeing with the plaintiff’s lead counsel that the Airport Link traffic model was “totally and utterly absurd”, and that “no reasonable traffic forecaster would ever prepare” such a model indicates that something more significant than incorrect assumptions were to blame.Regardless, the presence of any one of these reasons would betray a fundamental misunderstanding of context by traffic forecasters. This misunderstanding involves the difference between risk and criticality, and how these two concepts must be addressed in projects and business.In Australia risk is most often thought of as the simultaneous appreciation of likelihood and consequence for a particular potential event. In business contexts the ‘consequence’ of an event may be positive or negative; that is, a potential event may lead to better or worse outcomes for the venture (for example, a gain or loss on an investment).In project contexts these potential consequences are mostly negative, as the majority of the positive events associated with the project are assumed to occur. From a client’s point of view these are the deliverables (infrastructure, content, services etc.) For a consultant such as a traffic forecaster the key positive event assumed is their fee (although they may consider the potential to make a smaller profit than expected).Likelihoods are then attached to these potential consequences to give a consistent prioritisation framework for resource allocation, normally known as a risk matrix. However, this approach does contain a blind spot. High consequence events (e.g. client litigation for negligence) are by their nature rare. If they were common it is unlikely many consultants would be in business at all. In general, the higher the potential consequence, the lower the likelihood.This means that potentially catastrophic events may be pushed down the priority list, as their risk (i.e. likelihood and consequence) level is low. And, although it may be very unlikely, small projects undertaken by small teams in large consulting firms may have the potential to severely impact the entire company. Traffic forecasting for proposed toll roads appears to be a case in point. As a proportion of income for a multinational engineering firm it may be minor, but from a liability perspective it is demonstrably critical, regardless of likelihood.There are a range of options available to organisations that wish to address these critical issues. For instance, a board may decide that if they wish to tender for a project that could credibly result in litigation for more than the organisation could afford, the project will not proceed unless the potential losses are lowered. This may be achieved by, for example, forming a joint venture with another organisation to share the risk of the tender.Identifying these critical issues, of course, relies on pre-tender reviews. These reviews must not only be done in the context of the project, but of the organisation as a whole. From a project perspective, spending more on delivering the project than will be received in fees (i.e. making a loss) would be considered critical. For the Board of a large organisation, a small number of loss-making projects each year may be considered likely, and, to an extent, tolerable. But the Board would likely consider a project with a credible chance, no matter how unlikely, of forcing the company into administration as unacceptable.This highlights the different perspectives at the various levels of large organisations, and the importance of clear communication of each of their requirements and responsibilities. If these paradigms are not understood and considered for each project tender, more companies may find themselves in positions they did not expect.Also published on:https://sourceable.net/how-did-it-get-to-this-project-risk-vs-company-liability/

Should you attend the Engineering Due Diligence Workshop?

An introduction to the concept of Engineering Due Diligence

Engineering is the business of changing things, ostensibly for the better. The change aspect is not contentious. Who decides what’s ‘better’ is the primary source of mischief.

In a free society, this responsibility is morally and primarily placed on the individual, subject always to the caveat that you shouldn’t damage your neighbours in the process. Otherwise you can pursue personal happiness to your heart’s content even though this often does not make you as happy as you’d hoped. And it becomes rapidly more complex once collective cooperation via immortal legal entities known as corporations came to the fore as the best way to generate and sustain wealth. This is particularly significant for engineers as the successful implementation of big ideas requires large scale cooperative effort to the possible detriment of other collectives.

The rule of law underpins the whole social system. It is the method by which harm to others is minimised consistent with the principle of reciprocity (the golden rule – do unto others as you would have done unto you) prevalent in successful, prosperous societies. In Australia it has been implemented via the common law and increasingly, in statute law. Company directors, for example, have to be confident that debts can be paid when they fall due (corporations law), workers (and others) should not be put unreasonably at risk in the search for profits (WHS law) and the whole community should be protected against catastrophic environmental harm (environmental legislation). It is unacceptable for drink-drivers to kill and injure others, the vulnerable to be exploited or the powerful to be immune from prosecution. Everyone is to be equal before the law.

Provided such outcomes are achieved, the corporation and the individuals within them are pretty much free to do as they please. Monitoring all these constraints and ensuring the balance between individual freedoms and unreasonable harm (safety, environmental and financial) to others has become the primary focus of our legal system.

But the world is a complex place and its difficult to be aways right particularly when dealing with major projects. But it is entirely proper to try to be right within the limits of human skill and ingenuity. The legal solution to address all this has been via the notion of ‘due diligence’ and the ‘reasonable person’ test.

Analysing complex issues in a way that is transparent to an entire organisation, the larger society and, if necessary, the courts can be perplexing. Challenges arise in organisations when there are competing ideas of better, meaning different courses of action all constrained with finite resources. This EDD workshop provides a framework for the various internal and external stakeholders to listen to, understand and decide on the optimal course of action taking into account safety, environmental, operational, financial and other factors.

To be ‘safe’, for example, requires that the laws of nature be effectively managed, but done in a way that satisfies the laws of man, in that order.

Engineering Due Diligence Workshop

The learning method at the R2A & EEA public workshops follows a form of the Socratic ‘dialogue’. Typical risk issues and the reasons for their manifestation are articulated and exemplar solutions presented for consideration. The resulting discussion is found to be the best part for participants as they consider how such approaches might be used in their own organisation or project/s.

Current risk issues of concern and exemplar solutions include:

- Project schedule and cost overruns. This is much to do with the over-reliance on Monte Carlo simulations and the Risk Management Standard which logically and necessarily overlook potential project show-stoppers. A proven solution using military intelligence techniques will be articulated. This has never failed in 20 years with projects up to $2.5b.

- Inconsistencies between the Risk Management Standard and due diligence requirements in legislation, particularly the model WHS Act. A tested solution that integrates the two is presented, as is now being implemented by many major Australian and New Zealand organisations, shown diagrammatically below.

- Compliance does not equal due diligence. Solutions are provided to avoid over reliance on legal compliance as an attempt to demonstrate due diligence. It also demonstrates how a due diligence approach facilitates innovation.

- The SFAIRP v ALARP debate. Model solutions presented (if relevant to participants) including marine and air pilotage, seaport and airport design (airspace and public safety zones), power distribution, roads, rail, tunnels and water supply.

Participants are also encouraged to raise issues of concern. To enable open discussion and explore possible solutions, the Chatham House Rule applies to participants’ remarks meaning everyone is free to use the information received without revealing the identity or affiliation of the speaker.

To find out more information about the Engineering Due Diligence Workshop held in partnership with Engineering Education Australia, head to our workshop page or contact course facilitator, presenter and R2A Partner Richard Robinson at richard.robinson(@)r2a.com.au or call 1300 772 333.

If you're ready to register, do so direct via EEA website here.

Engineering: Ideas and Reality

Engineers play an integral role in bringing society’s wishes to fruition. As Engineers Australia’s monthly magazine create notes, we engineer ideas into reality.

However, when we go about taking ideas and making them real we have responsibilities. We are obliged to consider the ideas’ risks as well as benefits. We must ensure that our engineering activities meet our society’s expectations, and in particular that we address all our legal duties as engineers.

And so, even as we engineer new ideas into reality, we must also engineer the new reality we create into ideas – the ideas expressed in Australia’s laws.

Australia is an egalitarian society. Our judicial and political systems are predicted on the basis of equality for all before the law. This gives rise to a number of interesting ideals. For instance, one of our fundamental legal safety principles is that, for a known safety hazard, everyone is entitled to the same minimum level of protection. This arises from work health and safety legislation in all states and territories.

As another example of this, recognised good practice is a standard to which all engineers are held, in safety matters and otherwise. Engineering good practice is demonstrated in many ways, including standards and guidelines for design, operation, asset management and so on. It is also presented in regulations, which essentially present good practice that is so well recognised that the governments agree that it must be mandated. The National Construction Code is a prime example of this.

This reliance on recognised good practice means that, for instance, an engineering project manager who fails to implement recognised good practice measures to address the risk of project cost or timeline overrun would very likely expose his organisation to civil liabilities.

The simplest, cheapest and most effective way for engineers to address these and other legal requirements is to adopt systems and processes that demonstrate due diligence, that is, that all reasonable measures have been taken. This approach ensures engineering activities and engineering decisions are conducted in a manner consistent with legal requirements – that as we engineer ideas into reality, we also engineer reality to the right ideas.

To learn more about demonstrating due diligence as engineers, register for EEA’s Engineering Due Diligence workshop.

Regulators Put Cost Before Safety

A recent New York Times article presents a view as to what bought about the Grenfell tower fire disaster. It’s depressing reading, as it is clear that the hazards of associated with combustible cladding of aluminium-sheathed polyethylene and the like were a well-known fire hazard.

Personal memory as a young fire protection engineer being trained by Factory Mutual in the US in the ‘70s recalls being exhorted to ensure robust attachment, managed flue spaces and endless sprinklers as industrial de rigueur.

The fire at the Lacrosse Building - 2004 (The Age)

Inferno at Grenfell Tower (AFP PHOTO/Natalie Oxford)

The most alarming aspect of the NYT article is the argument that, despite repeated warning from competent parties, the regulators and politicians put the financial interests of the construction industry before safety. The article goes on to imply that had regulations banning this type of combustible cladding been in place (as is the case in many other countries), there is a significant chance that the Grenfell fire would not have occurred.

Whilst we suspect this to be true, the NYT argument, from R2A’s perspective, is flawed.

***

The UK Work Health and Safety at Work etc Act (1974), like the Victorian OHS ACT (2004) and the model WHS Acts in Australia calls up the legal principle of due diligence to a SFAIRP standard. That is, a known hazard should be eliminated, so far as is reasonably practicable, or if not eliminated, reduced so far as is reasonably practicable. The dangers of combustible external cladding in buildings are well known, as are the recognised good practice precautionary options available to manage them. Demonstrating due diligence that this has been achieved is morally sound and commercially obvious. It is also the law.

This suggests that the officers of the organisations responsible for the construction, approval and installation of the cladding all failed their duty of care. The question of whether or not specific regulations for combustible cladding were warranted is, in one sense, beside the point.

As we’ve previously stated, it is impossible to implement legislative prescription of specific safety measures for the essentially infinite ways in which people may be damaged. This is the reason for the qualifier ‘reasonable’ in overarching health and safety duties of care.

So then what is the purpose of health and safety regulations? Regulations are hindsight-driven legislation intended to mandate specific examples of recognised good practice. They often appear to arise from historical lessons. They set out minimum requirements that must be achieved under statutory law (as distinct from the less specific recognised good practice that is the minimum requirement under the common law). Regulations set a benchmark that must be achieved, but do not provide any guarantee that any overarching duty of care implied by a regulation’s superior Act is satisfied. And as the world changes, hindsight-driven regulations necessarily can't keep up.

Regulations, then, must be seen as an input to and check against any safety due diligence argument designed to address the overarching duty of care. They are neither starting point nor finishing line; they lie parallel to the safety due diligence process.

However, regulations and (even more commonly) standards called up by legislation are often seen as compliance targets. This appears to have a number of causes. One is the compliance culture that integrated with risk management a number of years ago. This had advantages, including a focus on consistency and documented decision-making processes. However, it can also lead to safety risks being addressed in a check-box fashion, and a lack of understanding that when dealing potential future events, some personal judgement is always required.

A second cause appears to be the increasing level of detail in some regulations. When designing and building to the Building Code of Australia, for instance, there are literally hundreds of pages of requirements that must be understood and addressed. There are, we are sure, good reasons for each BCA requirement, but the minute detail given can impart a false sense of completeness when addressing safety issues. In our experience, compliance with the BCA is often seen as the goal, rather than a component of a safety due diligence argument.

And, as we’ve also previously noted, when one asks any engineer if simply complying with regulations will make something safe they invariably laugh. Mere compliance with regulations does not make anything ‘safe’ per se, although it can prevent certain responsible parties (those with a duty of care) from going to jail if bad things happen. This is most certainly not the intent of any health and safety legislation.

***

Regulations prohibiting combustible cladding of aluminium-sheathed polyethylene are now a significant possibility in a number of jurisdictions, including Australia and the UK. But such regulations will not ensure developers and builders satisfy their overarching duty of care, merely that there is another target to meet. A wider focus on safety due diligence is needed.

Investigations into these fires are still underway in London and Melbourne, with the Victorian Government appointing a taskforce led by architect and former premier Ted Ballieau. We will watch their outcomes with interest.

Engineering Coming Into Focus

Doctor Iain McGilchrist will soon be in Australia to present to the 2017 Annual Conferences of Judges of the Federal and Supreme Courts of Australia. Dr McGilchrist is a psychiatrist and a former reader in English at Oxford University. Dr McGilchrist’s most recent book, The Master and His Emissary, has been discussed in an illustrated TED talk and is also the subject of an upcoming documentary.

The Master and His Emissary explores the evolution, interactions, workings and meanings of the human brain’s left and right hemispheres. In particular, he investigates and expands on the different roles the left and right hemispheres play in our interaction with, perception of, and understanding of the world.

One of the many interesting concepts discussed is the notion of the ‘gestalt’ in cognition and understanding. Comprehending the gestalt may be thought of as the appreciation of something as more than the sum of its parts – for example, the “ah-ha!” moment when meaning emerges from the image above.

Once the Dalmatian is perceived it becomes obvious, even though it is not ‘built’ from the component black blotches of the image. Appreciation of the gestalt is something for which the right hemisphere has a much great facility than the left. It excels in understanding context and individuality.

The left hemisphere, in contrast, tends to work with logic and analysis, systems, models, representations, classing and sorting, and so on. It assembles component parts into a known whole, to move in a linear fashion from a starting point to a finishing point – whether or not this remains in the proper context.

Ultimately both of these approaches are needed for problem-solving. Unfortunately, in engineering, there is sometimes a tendency to treat analysis as the whole of the solution. This particularly presents problems when the analysis is seen as ‘true’ or ‘real’. Ultimately a model is literally a re-presentation of the world – a simplified system built in terms that (we believe) we understand. As the statistician George E. P. Box noted, “all models are wrong, but some are useful”.

However, it is very difficult, and sometimes impossible, to simultaneously appreciate a gestalt and its components. As soon as one focuses absolutely on one blotch in the picture above, the Dalmatian disappears.

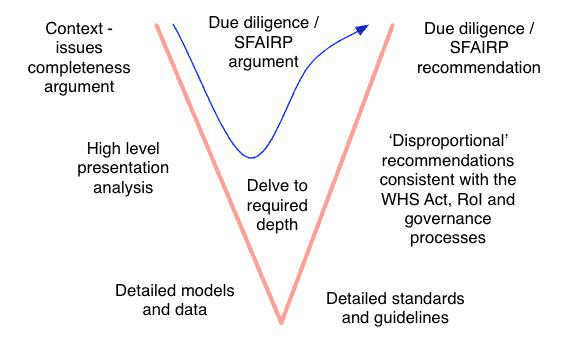

R2A has found an effective approach to problem-solving is the following ‘V’ process. The example below is for a generic safety issue, but the approach may be adapted to any problem.

One key is the understanding that detailed analysis may or may not be needed. Each problem is individual and unique, and providing convincing solutions to different groups of stakeholders each facing the same problem will often require different levels of detail. Keeping this in mind during analysis, with an understanding of the high level problem context and solution goals, assists in delving only to the analytical depth necessary.

A second key is the recognition that this is not a linear process. It may take the form of an ascending spiral, continually reviewing and refining past ideas as it moves towards resolution. Or a solution may, as with the Dalmatian image above, simply emerge from the assembly of data, as a picture coming into focus.

Either way, retaining the context and individuality of each problem is paramount to developing good solutions – engineering’s ultimate aim.

Engineering Due Diligence Workshop

The learning method at the R2A-EEA public workshops follows a form of the Socratic ‘dialogue’. Typical risk issues and the reasons for their manifestation are articulated and exemplar solutions presented for consideration. The resulting discussion is found to be the best part for participants as they consider how such approaches might be used in their own organisation or projects.

Current risk issues of concern and exemplar solutions include:

- Project schedule and cost overruns. This is much to do with the over-reliance on Monte Carlo simulations and the Risk Management Standard which logically and necessarily overlook potential project show-stoppers. A proven solution using military intelligence techniques will be provided. This has never failed in 20 years with projects up to $2.5b.

- Inconsistencies between the Risk Management Standard and due diligence requirements in legislation, particularly the model WHS Act. A tested solution that integrates the two is presented, as is now being implemented by many major Australian and New Zealand organisations.

- Compliance ≠ due diligence. Solutions to avoid over reliance on legal compliance as an attempt to demonstrate due diligence are provided.

- SFAIRP v ALARP debate. Model solutions presented (if relevant to participants) including marine and air pilotage, seaport and airport design (airspace and public safety zones), power distribution, roads, rail, tunnels and water supply.

Participants are also encouraged to raise issues of concern. To enable open discussion and explore possible solutions, the Chatham House Rule applies to participants’ remarks meaning everyone is free to use the information received without revealing the identity or affiliation of the speaker.

Remaining dates for 2017 are:

Perth 21 & 22 JuneBrisbane 23 & 24 AugustWellington 5 & 6 SeptemberMelbourne 25 & 26 October