Why SFAIRP is not a safety risk assessment

Weaning boards off the term risk assessment is difficult.

Even using the term implies that there must be some minimum level of ‘acceptable safety’.

And in one sense, that’s probably the case once the legal idea of ‘prohibitively dangerous’ is invoked.

But that’s a pathological position to take if the only reason why you’re not going to do something is because if it did happen criminal manslaughter proceedings are a likely prospect.

SFAIRP (so far is as reasonably practicable) is fundamentally a design review. It’s about the process.

The meaning is in the method, the results are only consequences.

In principle, nothing is dangerous if sufficient precautions are in place.

Flying in jet aircraft, when it goes badly, has terrible consequences. But with sufficient precautions, it is fine, even though the potential to go badly is always present. But no one would fly if the go, no-go decision was on the edge of the legal concept of ‘prohibitively dangerous’.

We try to do better than that. In fact, we try to achieve the highest level of safety that is reasonably practicable. This is the SFAIRP position. And designers do it because it has always been the sensible and right thing to do.

The fact that it has also been endorsed by our parliaments to make those who are not immediately involved in the design process, but who receive (financial) rewards from the outcomes, accountable for preventing or failing to let the design process be diligent is not the point.

How do you make sure the highest reasonable level of protection is in place? The answer is you conduct a design review using optimal processes which will provide for optimal outcomes.

For example, functional safety assessment using the principle of reciprocity (Boeing should have told pilots about the MCAS in the 737 MAX) supported by the common law hierarchy of control (elimination, prevention and mitigation). And you transparently demonstrate this to all those who want to know via a safety case in the same way a business case is put to investors.

But the one thing SFAIRP isn’t, is a safety risk assessment. Therein lies the perdition.

Simplifying Hierarchy of Control for Due Diligence

The hierarchy of control is one of those central ideas that safety regulators have been using forever. But it is also one of those very simple ideas that has caused enormous confusion in due diligence.

In hierarchical control terms, the WHS legislation (or OHS in Victoria) provides for two levels of risk control: elimination so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP), and if this cannot be achieved, minimisation SFAIRP.

In addition, criminal manslaughter provisions have been enacted in many jurisdictions.

The post-event test for this will be the common law test albeit to the statutory beyond reasonable doubt criteria.

For example, from WorkSafe Victoria:

The test is based on the existing common law test for criminal negligence in Victoria, and is an appropriately high standard considering the significant penalties for the new offence.

https://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/victorias-new-workplace-manslaughter-offences

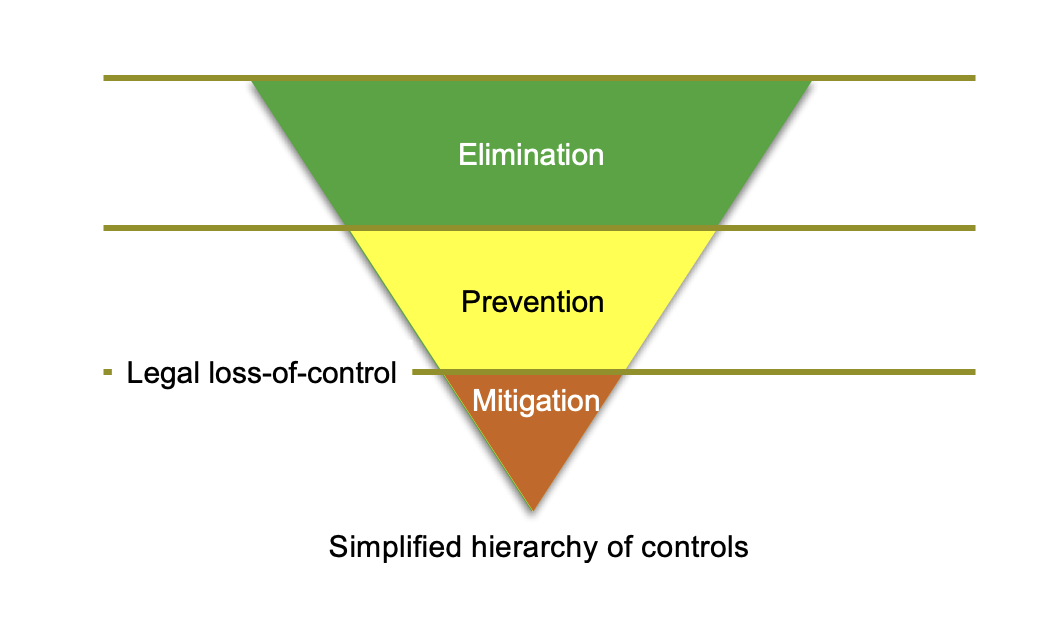

Post-event in court, from R2A’s experience acting as expert witnesses, there are three levels in the hierarchy of control:

- Elimination,

- Prevention, and

- Mitigation.

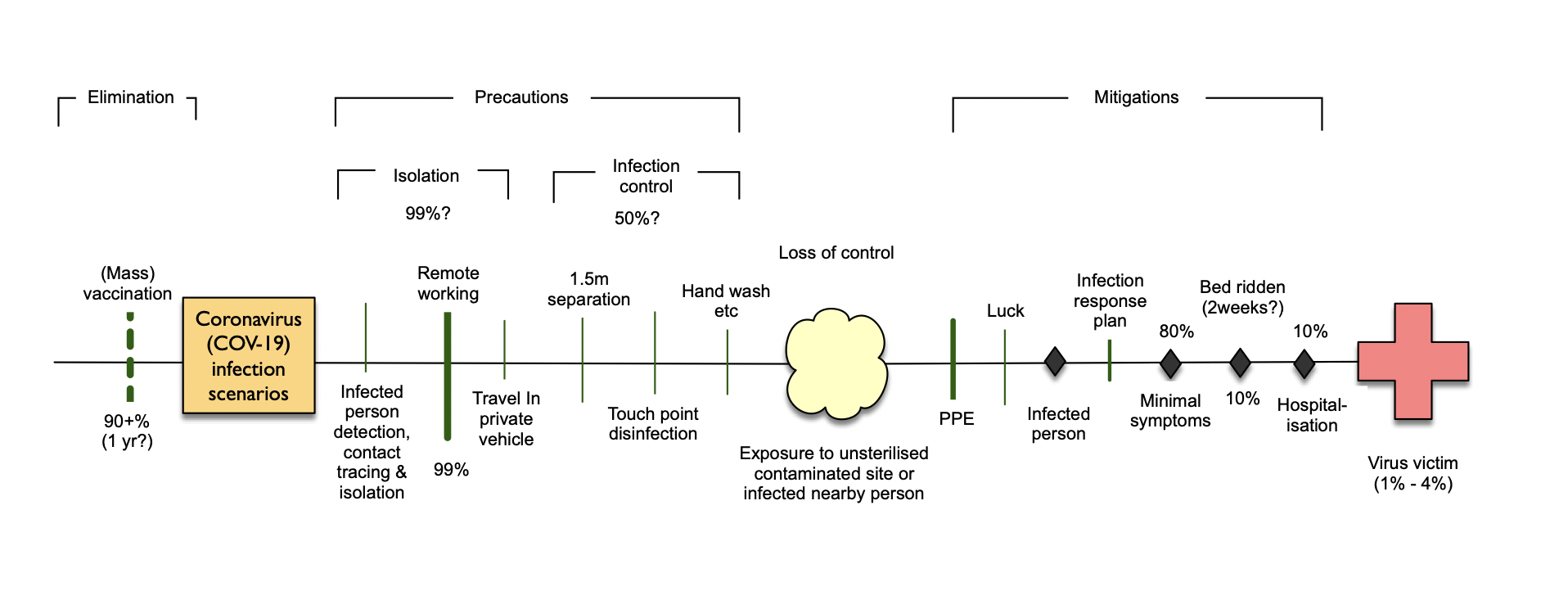

In causation terms most simply shown as single line threat-barrier diagrams such as the one for Covid 19 below.

Our collective safety regulators have other views. For example, the 2015 Code of Practice (How to Manage Work Health and Safety Risks) which has been adopted by ComCare and NSW has 3 levels of control measures whereas many other jurisdictions adopt the 6-level system like Western Australia. Victoria has a 4-level system.

This inconsistency between jurisdictions seriously undermines the whole idea of harmonised safety legislation. And it also muddles optimal SFAIRP control outcomes. For example, engineering can be an elimination option, as in removing a navigation hazard, a preventative control as in machine guarding, or a mitigation as in an airbag in a car.

In R2A’s view, which we have tested with very many lawyers, the judicial formulation shown below is the only hierarchy of control capable of surviving legal scrutiny and R2A’s preferred approach.

Contact the team at R2A Due Diligence for further advice on hierarchy of controls for due diligence.

SFAIRP Culture

The Work Health & Safety (WHS) legislation has changed the way organisations are required to manage safety issues. With the commencement of the legislation in WA on 31 March 2022, as well as the introduction of criminal manslaughter provisions in some states, there appears to be an increased energy around safety due diligence.

The legislation requires SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable).

A duty imposed on a person to ensure health and safety requires the person:

(a) to eliminate risks to health and safety, so far as is reasonably practicable; and

(b) if it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate risks to health and safety, to minimise those risks so far as is reasonably practicable.

This means that the historical concepts of ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable), risk tolerability and risk acceptance do not apply.

From the handbook for the Risk Management Standard (ISO 31000):

Importantly, contemporary WHS legislation does not prescribe an ‘acceptable’ or ‘tolerable’ level of risk—the emphasis is on the effectiveness of controls, not estimated risk levels. It may be useful to estimate a risk level for purposes such as communicating which risks are the most significant or prioritising risks within a risk treatment plan. In any case, care should be taken to avoid targeting risk levels that may prevent further risk minimisation efforts that are reasonably practicable to implement.

(SA/SNZ HB 205:2017 page 14)

In cultural terms, James Reasons outlines three types of risk culture: pathological, bureaucratic and generative.

The SFAIRP approach is attempting to move safety from the pathological question: Is this bad enough that we have to do something about it, to the generative perspective: Here’s a good idea, why wouldn’t we do it?

In this framework, Codes of Practice and Standards are the bureaucratic starting point. The objective is to do better than that, when reasonably practicable to do so. The aim is the highest reasonable level of protection.

The Act ensures a ‘transparent bias’ in favour of safety. As the model act says (and all jurisdictions including NZ have adopted):

… regard must be had to the principle that workers and other persons should be given the highest level of protection against harm to their health, safety and welfare from hazards and risks arising from work as is reasonably practicable.

This is a change in mindset for many organisations, but one which easily aligns with human nature.

On a personal level, we (at R2A) are always trying to do the best we can especially for others. This is one of the reasons I continue to work on Apto PPE, a line of fit-for-purpose female hi vis workwear including a maternity range.

I know that females only represent a small proportion of the engineering and construction section (around 10%), but the question shouldn’t be “is the current options of PPE for women bad enough that we need to do something about it?”

The question should be: Can we do better than scaled down men’s PPE? And Apto PPE is happy to provide an option for organisations that want to do better.

SFAIRP Land Use Planning

One of the little recognised consequences of the use of SFAIRP is its implications for land use planning, particularly for industries that can have significant offsite consequences like major hazards facilities (MHFs), dams and licensed pipelines.

The whole point of the WHS legislation is to avoid unreasonably injuring your neighbour. As the Brisbane born English law lord, Lord Atkin put it in 1932:

Who then in law is my neighbour? The answer seems to be persons who are so closely affected by my act that I ought reasonably have them contemplation as so being affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called into question.

We are not aware of any regulator in any Australian or New Zealand jurisdiction that disagrees with his view.

Applying the SFAIRP process means spelling out the credible worst case scenario for the facility of interest. Then it must be made plain to everyone that this is the case so that relevant neighbours, especially Council planners and developers, can design accordingly.

Decreasing SFAIRP precautionsconsistent

From a design perspective, every site has issues; this can include windstorm hazards, geotechnical and earthquake potentials, storm surge, flooding and inundation, lightning strike potentials, etc. For the design to be successful, all these must be addressed.

Adopting the SFAIRP approach to land use planning in these circumstances means that the closer to the hazard a structure is, the greater the precautions need to be. In principle, provided the level of protection is high enough, there are no limits to where a structure could be built in relation to the major hazard facility presented above.

The fact that there is a MHF chemical exposure, gas transmission pipeline, or dam upstream is just another hazard to be managed.

If in order to be safe, people wind up in an unaffordable, unattractive, underground air conditioned bunker, then it may be that the project will not proceed, but this would be for commercial reasons, not SFAIRP safety ones.

R2A have completed a number of these land use planning reviews over the last five years or so. To check for off-site credible fire scenarios, R2A use a common and reasonably user-friendly CFD program, Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS).

As a result of our SFAIRP reviews, all stakeholders including the pipeline business, the developers and architects and the regulator have agreed to the level of protections / precaution required to demonstrate SFAIRP.

Plan View 100 m x 100 m Kerosene Pool Fire with 20 kt wind

You may also be interested in listening to Richard & Gaye discussing Land Use Planning & Major Hazards in this Risk! Engineers Talk Governance podcast episode.

Due Diligence & Risk Timeline Arguments

When you know there are problems but have insufficient resources to fix them all at once…

During a recent discussion with a client, the topic of risk timelines came up and I realised that although we use it as a background concept in much of our work we haven’t articulated it in our textbooks or previous blogs.

The idea of a risk timeline approach recognises that you can’t do everything all at once because there are always constraints – time, people and resources.

Unless the situation is prohibitively dangerous for a critically exposed group (in which case the activity needs to be stopped and addressed immediately) then a risk timeline approach can be used.

Contemporary WHS/OHS legislation requires risks be eliminated so far as is reasonably practicable, and if they can’t be eliminated, reduced SFAIRP.

This means that the focus of a risk timeline argument is always on solutions.

A risk timeline argument includes:

A program to address each particular issue of concern over a specified timeframe

A list of prioritised works; we at R2A would suggest based on safety criticality first

Categorisation of potential controls in terms of short, medium and long term SFAIRP solutions or options

Identification and recognition of opportunities to address known issues of concern during other works especially major upgrades.

The key of a risk timeline argument, however, is to make sure that:

funding is available to start the program,

works are underway, and that there is

a realistic, believable program in place to achieve the desired results.

The management of credible critical issues of concern, even if rare, cannot be deferred indefinitely.

If you'd like to discuss risk timelines for your due diligence project, please contact us.

Environmental Protection now SFAIRP

A while back, R2A had a blog entitled Precaution v Precaution wherein we wondered how the precautionary principle (derived from the 1992 Rio Convention) enunciated in the then Environmental Protection Act in Victoria compared to the SFAIRP approach of OHS/WHS legislation.

Well, we have the answer! In Victoria at any rate.

From 1 July 2021, SFAIRP is paramount. It is formally included in the Environmental Protection Act 2017. Victorians now have a duty to positively demonstrate due diligence for both safety and the environment.

Similar to the WHS/OHS Acts, Section 6 of the revised act states:

(1) A duty imposed on a person under this Act to minimise, so far as reasonably practicable, risks of harm to human health and the environment requires the person -

(a) to eliminate risks of harm to human health and the environment so far as reasonably practicable; and

(b) if it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate risks of harm to human health and the environment, to reduce those risks so far as reasonably practicable.

Section 18 describes the hierarchy of waste control:

Waste should be managed in accordance with the following order of preference, so far as reasonably practicable -

- avoidance;

- reuse;

- recycling;

- recovery of energy;

- containment;

- waste disposal.

Strangely, Section 20 retains the Rio Convention approach:

If there exist threats of serious or irreversible harm to human health or the environment, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent or minimise those threats.

Section 25 summarises a General Environmental Duty (GED):

A person who is engaging in an activity that may give rise to risks of harm to human health or the environment from pollution or waste must minimise those risks, so far as reasonably practicable.

In attempting to explain the significance of all this, it’s probably important to understand that this is actually a lawyers’ articulation of a principle of moral philosophyinitially inserted into the common law by the Brisbane born English law lord, Lord Atkin (Donoghue v Stevenson (1932), and which has subsequently flowed into Australian statute law:

The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer's question "Who is my neighbour?" receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour.

Who then in law is my neighbour? The answer seems to be persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question.

This is just the principle of reciprocity: do unto others as you would have done unto you.

With that understanding, much of the legal palaver becomes quite obvious.

In dam safety terms, for example, it asks the question:

“If you lived downstream of a large dam, how would you expect the dam to be designed and managed in order to be safe?”

Even though the dam meets recognised good practice for design, operation and maintenance, if more could be done to make the dam safer at reasonable cost, ought that not be done?

After all, if the dam failed, and there was a simple cost-effective precaution that could have prevented the disaster, shouldn’t it have been done? And oughtn’t people who have lost loved ones be cranky with those who failed to do those reasonable things?

This is probably where this new SFAIRP approach has the greatest impact. It is no longer acceptable to say that you complied with an Australian or other standard.

Standards are just the starting point. You must do more if you reasonably can, a matter which will be forensically tested post-event.

Indeed, if you use a standard as the design tool, without testing if more can reasonably be done, you are probably already in breach of the legislation.

As Paul Wentworth, a partner in Minter Ellison put it in 2011:

… in the performance of any design, reliance on an Australian Standard does not relieve an engineer from a duty to exercise his or her skill and expertise.

If you would like to discuss how this may affect your organisation's obligations or due diligence in general, contact us for a chat.

Why Hazops fail the SFAIRP test & why this is important

R2A recently presented a free webinar; Why Hazops fail the SFAIRP test. It is one of the more frequently asked questions we receive as Due Diligence Engineers.

Hazops are a commonly used risk management technique, especially in the process industries. In some ways the name has become generic; in the sense that many use it as a safety sign-off review process prior to freezing the design, a bit like the way the English hoover the floor when they actually mean vacuum the floor.

Traditionally, Hazop (hazard and operability) studies are done by considering a particular element of a plant or process and testing it against a defined list of failures to see what the implications for the system as a whole might be. That is, they are bottom-up in nature and so provide a detailed technical insight into potential safety and operational issues of complex systems. They can certainly produce important results.

However, like many bottom-up techniques they have problems with identifying high-consequence common-cause and common-mode failures. This arises simply because the Hazop process is bottom-up in nature rather than top-down.

A detailed assessment of individual components or sub-systems like Hazops examine how that component or sub-system can fail under normal operating conditions.

Hazops do not examine how a catastrophic failure elsewhere (like a fire or explosion) might simultaneously affect this component or the others around it.

Such ‘knock-on’ effects are attempted to be addressed in Hazops by a series of general questions after the detailed review is completed, but it nevertheless remains difficult to use a Hazop to determine credible worst-case scenarios.

This is exacerbated by the use of schematics to functionally describe the plant or equipment being examined. Unless the analysis team has an excellent spatial / geographic understanding of the system being considered, it’s very hard to see what bits of equipment are being simultaneously affected by the blast, fire or toxic cloud.

This means that it is difficult to use a Hazop to determine credible worst-case scenarios and ensure SFAIRP has been robustly demonstrated for all credible, critical hazards.

For a limited time, you can watch the webinar recording of the presentation on Why Hazops cannot demonstrate SFAIRP here.

If you’d like to discuss any aspect of this article, your due diligence / risk management approaches, or how we can conudct an in-house briefing on a particular organisational due diligence issue, contact us for a chat.

R2A’s MISSION STATEMENT

the work we do: People as an ends, not means & Making a Difference

Last year’s extended Covid-19 lockdown in Victoria meant many in business reviewed what they do, how they do it and, ultimately, why they do it.

R2A, as a small firm of consulting engineers, has always had a business view that has seemed a little different to many we encounter. Whist we understand the need to be profitable, that has never been the primary motivation.

We have always felt that what we do must be worthwhile, not just to ourselves but for the people (our clients) for whom we do it.

Practically, if we can’t make sense of what we are being asked to do, we decline to keep doing it, to the very great surprise and puzzlement of well-paying customers.

The decision to reject a client and potentially put the business under serious financial stress does cause a certain introspection, and retest the proposition; why are we here and why are we doing it?

Ultimately, the reason is that we believe we make a difference.

That what R2A is and does improves the place, and, when we have likeminded clients, it’s a joy to do. And we get paid to do it. Such an understanding means that we want to get up and go to work.

It also has other flow on effects. In the philosopher Immanuel Kant’s terms, it means you treat people as ends in themselves, not merely a means to an end. This rejects traditional authoritarian hierarchical management styles.

Rather than telling people what to do and how to do it, you provide ‘pits of opportunity’ for them to fall into and see how they go. When it succeeds, results are outstanding and extraordinary. Focussed, effective enthusiasm abounds.

In this context, it may surprise some of our clients to know that R2A owns a small female PPE business, Apto PPE.

Apto is the result of Gaye’s involvement with the Women in Engineering Group at Engineers Australia and a collective frustration with being forced to wear ill-fitting scaled down men’s PPE onsite. The intention of the Apto business was to force the market to respond and deliver a better outcome for women in industry. This necessitated the design, manufacture and small-scale sale of tested superior women’s PPE garments in Australia.

For the most part this strategy has worked, although it appears that unless the pressure is sustained on the market, it will revert. To this end the R2A board has determined that R2A will continue to sponsor Apto until it becomes a self-sustaining business.

We make this decision continuing to align with why we’re in business; believing we’ll make a difference.

Gaye Francus & Richard Robinson

Why Due Diligence is now a 'Categorical Imperative'

WA adopts WHS legislation with criminal manslaughter provisions

NZ charges 13 under HSWA over White Island eruption that killed 22

The adoption of the model WHS legislation in Australasia is now practically complete with the passing of the act by the Western Australian parliament. Whilst yet to be proclaimed, the WA version includes criminal manslaughter provisions with a maximum penalty of 20 years for individuals.

Victoria is now formally the only state not to have adopted the model WHS Act, although this is practically inconsequential, as the due diligence concept to demonstrate SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable) is embodied in the 2004 OHS Act, and the criminal manslaughter provisions of same commenced on the 1st of July this year.

New Zealand adopted the model WHS legislation in the form of the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015. Judging by the number of commissions R2A has had in NZ in 2020, it has come as a bit of a surprise to many, particularly to those using the hazard-based approach of target levels of risk and safety such as ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable), that these have been completed superseded by the new legislation and cannot demonstrate safety due diligence.

New Zealand has not presently adopted the criminal manslaughter provisions being introduced into Australia, but it did include the significant penalties for recklessness (knew or made or let it happen) with up to 5 years jail for individuals.

In all Australasian jurisdictions, regulators appear prosecutorially active with a number of cases presently under investigation and before the courts. For example, the White Island volcano incident in New Zealand which killed 22. Ten parties and 3 individuals have been charged.

Perhaps what has surprised many in NZ is the observation by NZ Worksafe, that for critical (kill or maim) hazards like volcanic eruptions, it only has to be reasonably foreseeable, not actually have happened before. That is, the fact that the hazard has not occurred before is not sufficient to warrant not thinking about it any further.

All in all, due diligence has become endemic, to the point that it has become, in the philosopher Immanuel Kant’s terms, a categorical imperative.

That is, our parliamentarians and judges seem to have decided that due diligence is universal in its application and creates a moral justification for action. This also means the converse, that failure to act demands sanction against the failed decision maker, which is being increasingly tested in our courts.

The Laws of Man vs The Laws of Nature & Safety Due Diligence

One of the odder confusions that R2A happens upon is the proposition that the laws of man are always paramount in all circumstances. It seems to occur most often with persons who work exclusively in the financial sector.

From an engineering perspective, this is just plain wrong.

When dealing with the natural material spacetime universe, the laws of nature are always superior.

After some cogitation, we suspect that this confusion results from the substance of which the financial parties contend, specifically, money.

Sometime ago, over lunch with a banker out of Hong Kong, it was pointed out by R2A that money wasn’t real. The banker expressed surprise and asked what we meant by that. Our reply was that money does not exist in a state of nature. For example, it does not grow on trees. It is a human construct which prosperous societies apparently need to succeed, but of itself, is not directly subject to the laws of nature.

The banker’s response was to ask us not to mention this to anyone.

From this, we conclude that for financial people at least, compliance with legislation and regulations made under it that directly applies to the concept and use of money does demonstrate financial due diligence since the laws of nature are simply not relevant.

However, in the case of safety due diligence, just complying with the laws of man and ignoring the laws of nature will just end in disaster after disaster since the laws of nature are immutable.

To demonstrate safety due diligence requires that the laws of nature are understood and managed in a way that satisfies the laws of man – in that order.

Remember that, legally, safety risk arises because of insufficient, inadequate or failed precautions, not because something is intrinsically hazardous.

For example, flying in a jet aircraft or getting into low earth orbit is intrinsically hazardous, but with enough precautions, it’s fine.

Leave a critical precaution out or let one fail and you will crash and burn. It’s inevitable.

Much the same has been happening with the Covid-19 crisis as discussed in our blog a few months ago (read article here).

Going directly to a political fix without understanding the science is going to hurt. Getting both right is necessary, but it has to be in the right sequence.

Overall, it’s always been no contest – the laws of nature have always trumped the laws of man, except when dealing with non-natural human constructs like money, debt and suchlike over which the laws of nature have no direct control.

Postscript: Risk, as a concept, has many of the same problems as money. It’s a human judgement about what might happen.

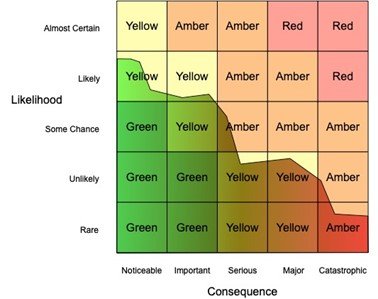

For example, consider the use of the popularly used heat map shown below.

Most users spot-the-dot to characterise the risk associated with a particular issue. But technically it is necessary to know the actual shape of the risk curve for that hazard (the wriggly line going from left to right) which is difficult for real spacetime hazards let alone human judgements of no-material constructs like money.

Strictly it’s also necessary to integrate the area under the risk curve (shown as the darkened area), which is never done. This just goes to show how flexible the concept of risk can be.

Criminal Manslaughter - Australian paradigm shift for engineers & standards

The rise of criminal manslaughter provisions in health and safety legislation, coupled with the registration of engineers in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria, heralds a paradigm shift for engineers and the role of standards in Australian jurisdictions.

On July 2020, Victoria commenced the criminal manslaughter provisions of the 2004 OHS Act. Quoting the premier:

Workplace manslaughter is now a criminal offence in Victoria with tough new laws introduced by the Victorian Government coming into effect today.

Negligent employers now face fines of up to $16.5 million and individuals face up to 25 years in jail, sending a clear message to employers that putting lives at risk in the workplace will not be tolerated.

The new offence of workplace manslaughter will be investigated by WorkSafe Victoria, using their powers under the Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004.

The offence applies to employers, self-employed people and ‘officers’ of the employer. It also applies when an employer’s negligent conduct causes the death of a member of the public.

The last sentence suggests that a faulty product that kills a member of the public caused by the negligence of a designer, manufacturer or supplier as an employer is also included.

By negligence, Worksafe Victoria means:

Voluntary and deliberate conduct is 'negligent' if it involves a great falling short of the standard of care that a reasonable person would have exercised in the circumstances and involves a high risk of death, serious injury or serious illness. It is a test that looks at what a reasonable person in the situation of the accused would have done in the circumstances. The test is based on existing common law principles in Victoria.

https://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/victorias-new-workplace-manslaughter-offences

It is understood that these new provisions have been legislated consistent with the recommendations of the 2018 review of the model WHS legislation to enhance the Category 1 offence (Recommendation 23a) and to provide for industrial manslaughter (Recommendation 23b).

This extends the criminal provisions beyond the recklessness (knew or made or let it happen) provisions that had applied in some jurisdictions (notably Queensland and the ACT) to include negligence (what ought to have been known).

Taken in the context of the registration of engineersin Queensland (RPEQ) and impending registration of engineers in Victoria andNew South Wales, these duties are likely to become extraordinarily onerous forthose who hold themselves out to be technical experts in particular fields ofendeavour.

Historically,many engineers have relied on Australian Standards to be the arbiter ofrecognised good practice. Indeed, many standards were called up by statutemeaning that compliance was prescriptive, and that compliance-with-the-standardwas de rigueur.

But things have changed in the last two decades. Parliamentary counsels’ advice has been consistent that it’s not appropriate to derogate the power of parliament to unelected standards committees.

This observation, coupled with the less than successful management of major disasters ranging from bushfires to financial crises, culminating in numerous Royal Commissions and judicial investigations including child sexual abuse, misconduct in banking and finance, aged care, as well as bushfires, all indicate that more could have been done and that many ought to have done it.

It seems that the question to our parliamentarians became; how can we make decision makers (and designers responsible) for their decisions?

And theanswer seems to be that, rather than just being responsible at common law fornegligence (a matter for which insurance can be purchased), make themcriminally responsible by statute (but always excluding state and federalministers).

Note relevant legal opinion such as in an article in Engineers Australia Magazine of March 2009 (Page 38):

Engineers cannot avoid liability in negligence or for Trade Practices Act contravention by simply relying on a current or published standard or code.

Leigh Duthie, Phillipa Murphy and Angela Sevenson of Baker & McKenzie, Melbourne

And also:

Engineers should remember that in the eyes of the court, in the absence of any legislative or contractual requirement, an Australian Standard amounts only to an expert opinion about usual or recommended practice. Also, that in the performance of any design, reliance on an Australian Standard does not relieve an engineer from a duty to exercise his or her skill and expertise.

Paul Wentworth, Partner, Minter Ellison (28th March 2011)

So, following the recommendation of the Review of the model Work Health and Safety laws - Final report December 2018, criminal recklessness (knew of made or let it happen) and criminal negligence (ought to have known) is being rolled out with Victoria being the most recent that commenced on 1 July 2020.

One imagines that a creative lawyer would use such a statement to include the products of engineering endeavours, which in an advanced technological society means most things.

Under the Professional Engineers Registration Act 2019 (due to commence on 1 July 2021), registered engineers are also obliged to comply with approved codes of conduct which one imagines will also reinforce all of this.

The importance of Safety Due Diligence: Keeping directors out of jail

Coroner's Finding into Dreamworld Thunder River Rapids

The death of four young people at Dreamworld in the Thunder River Rapids in October 2016 has brought the prospect of criminal prosecution of Directors for safety failures to the fore, or, as we say, Safety Due Diligence.

Press reports have indicated that the Queensland Government has accepted the Coroner's findings and referred the matter to the independent Work Health and Safety Prosecutor to decide whether action would be taken against Ardent, the owners of Dreamworld. Presumably such action would likely be criminal proceedings under Section 31 Reckless conduct—category 1 of the Qld WHS Act 2011.

Reckless Category 1 offences are usually summarised as ‘knew or made or let it happen’. Simply put, it asks:

Did the Board (especially the Chairman and Managing Director of the day) know of the issue and ensure that all reasonably practicable precautions were in place, or had they downplayed it and relied on ‘luck’?

Based on press reports, it seems as though the ride’s safety issue was a known problem and despite the expressed concerns of employees, it was basically ignored or, at least, not taken seriously.

Criminal offences must be proved ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ which is a very robust test.

To give a feeling for what it entails, the prosecution of a General Manager in ACT in 2015[1] provides insight.

In this case the Director of Public Prosecutions acted on behalf of Worksafe ACT. Essentially, Mr Munir AL-Hasani was charged as an Officer (General Manager) of Kenoss Constructions, a small family owned (husband and wife directors) road construction company. over the death of a contractor.

For the most part, the charges were proved. However, during the hearing it became clear that despite the title of general manager, Mr AL-Hasani did not have the right to hire or fire and could not commit corporate funds. Accordingly, Magistrate Walker was not satisfied that Mr AL-Hasani’s role, beyond reasonable doubt, rose to that of an Officer of the company and so the charge was dismissed.

Such a governance detail seems unlikely to apply to the Dreamworld case. The Chairman and Managing Director would appear to be Officers for the purposes of the legislation.

According to the Coroner, the issue was known to the organisation and some precautions, but not all reasonably practical precautions, were established.

From R2A’s perspective, this would seem to be a form of failure based on the well-known ‘Rumsfeld manoeuvre’ or an ‘unknown known’. That is, known to the organisation but unappreciated by decision makers.

Can this be proved beyond reasonable doubt in the Dreamworld case? We don’t know, but we suspect that it will be a close-run thing.

At R2A we had anticipated that the rise of such WHS safety imperatives was likely to cause the appointment of technologically savvy Directors; at least in high tech industries subject to high consequence-low likelihood events and in those jurisdictions where proven failure was criminal (initially Qld and ACT). But since then most other Australian jurisdictions have also adopted criminal manslaughter provisions.

All in all, what happens in Queensland next will certainly have the undivided attention of Directors and their safety due diligence processes. As it should.

If you'd like to learn more about R2A's Safety Due Diligence approach, you may be interested in watching our Safety Due Diligence webinar recording.

[1]Brett McKie v Munir AL-Hasani & Kenoss Contractors Pty Ltd (In Liq).Industrial Court of the Australian Capital Territory before her Honour IndustrialMagistrate Walker.

Coronavirus Pandemic & Safety Due Diligence

A fabulous array of material has emerged on government websites regarding the Coronavirus (COVID-19). Worksafe Australia has published an interesting article on the connection to WHS legislation. This emphasises that employers have a duty of care to eliminate or minimise risk, so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP).

There then follows numerous precautions described in enormous and voluminous detail. In an attempt to cut to the chase, R2A decided to apply our usual precautionary approach to the whole thing to see if we clarify what all this means.

So far as we can tell, the core difficulty with the new coronavirus is that it is very, very contagious. Much more so than ordinary flu.

This means it will escalate with startling speed and easily overwhelm our medical resources unless stringent measures to reduce the infection rate are implemented.

To calculate the infection rate, a probabilistic epidemiological model appears to be being used, conceptually shown above. That is, all the individual transmission pathways may not be fully understood, but an overall probabilistic transmissivity model can be created.

From a statistical viewpoint, if enough people are involved, the predictions should be quite robust and is presumably the basis of our governments’ concerns.

Causal workplace infection pathway single line threat barrier diagram

Following the hierarchy of controls, the threat-barrier diagram above identifies the elimination option (a vaccine), the precautions such as isolation and infection control prior to the loss of control point and then the mitigation options including hospitalisation which act after the loss of control point.

However, from the perspective of any single infection, there will likely be a single causal chain of events, which can be interrupted in various ways, particularly following the hierarchy of controls enshrined in the WHS legislation.

Such an understanding enables SFAIRP to be demonstrated. There would be different sequences for different paths; family, hospitals, workplace, team sports and the like.

From an employer /employee perspective, we think the single line threat-barrier diagram shown above is a reasonable first cut.

If you'd like to learn more about our Safety Due Diligence approach, read our White Paper here.

Worse Case Scenario versus Risk & Combustible Cladding on Buildings

BackgroundThe start of 2019 has seen much media attention to various incidents resulting from, arguably, negligent decision making.One such incident was the recent high-rise apartment building fire in Melbourne that resulted in hundreds of residents evacuated.The fire is believed to have started due to a discarded cigarette on a balcony and quickly spread five storeys. The Melbourne Fire Brigade said it was due to the building’s non-combustible cladding exterior that allowed the fire to spread upwards. The spokesperson also stated the cladding should not have been permitted as buildings higher than three storeys required a non-combustible exterior.Yet, the Victorian Building Authority did inspect and approve the building.Similar combustible cladding material was also responsible for another Melbourne based (Docklands) apartment building fire in 2014 and for the devastating Grenfell Tower fire in London in 2017 that killed 72 people with another 70 injured.This cladding material (and similar) is wide-spread across high-rise buildings across Australia. Following the Docklands’ building fire, a Victorian Cladding Task Force was established to investigate and address the use of non-compliant building materials on Victorian buildings.Is considering Worse Case Scenario versus Risk appropriate?In a television interview discussing the most recent incident, a spokesperson representing Owners’ Corporations stated owners needed to look at worse case scenarios versus risk. He followed the statement with “no one actually died”.While we agree risk doesn’t work for high consequence, low likelihood events, responsible persons need to demonstrate due diligence for the management of credible critical issues.The full suite of precautions needs to be looked at for a due diligence argument following the hierarchy of controls.The fact that no one died in either of the Melbourne fires can be attributed to Australia’s mandatory requirement of sprinklers in high rise buildings. This means the fires didn’t penetrate the building. However, the elimination of cladding still needs to be tested from a due diligence perspective consistent with the requirements of Victoria’s OHS legislation.What happens now?The big question, beyond that of safety, is whether the onus to fix the problem and remove / replace the cladding is now on owners at their cost or will the legal system find construction companies liable due to not demonstrating due diligence as part of a safety in design process?Residents of the Docklands’ high-rise building decided to take the builder, surveyor, architect, fire engineers and other consultants to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) after being told they were liable for the flammable cladding.Defence for the builder centred around evidence of how prevalent the cladding is within Australian high-rise buildings.The architect’s defence was they simply designed the building.The surveyor passed the blame onto the Owners’ Corporation for lack of inspections of balconies (where the fire started, like the most recent fire, with a discarded cigarette).Last week (at the time of writing), the apartment owners were awarded damages for replacement of the cladding, property damages from the fire and an increase in insurance premiums due to risk of future incidents. In turn, the architect, fire engineer and building surveyor have been ordered to reimburse the builder most of the costs.Findings by the judge included the architect not resolving issues in design that allowed extensive use of the cladding, a failure of “due care” by the building surveyor in its issue of building permit, and failure of fire engineer to warn the builder the proposed cladding did not comply with Australian building standards.Three percent of costs were attributed to the resident who started the fire.Does this ruling set precedence?Whilst other Owners’ Corporations may see this ruling as an opportunity (or back up) to resolve their non-compliant cladding issues, the Judge stated they should not see it as setting any precedent.

"Many of my findings have been informed by the particular contracts between the parties in this case and by events occurring in the course of the Lacrosse project that may or may not be duplicated in other building projects," said Judge Woodward.

If you'd like to discuss how conducting due diligence from an engineering perspective helps make diligent decisions that are effective, safe and compliant, contact us for a chat.

Australian Standard 2885, Pipeline Safety & Recognised Good Practice

Australian guidance for gas and liquid petroleum pipeline design guidance comes, to a large extent, from Australian Standard 2885. Amongst other things AS2885 Pipelines – Gas and liquid petroleum sets out a method for ensuring these pipelines are designed to be safe.

Like many technical standards, AS2885 provides extensive and detailed instruction on its subject matter. Together, its six sub-titles (AS2885.0 through to AS2885.5) total over 700 pages. AS2885.6:2017 Pipeline Safety Management is currently in draft and will likely increase this number.

In addition, the AS2885 suite refers to dozens of other Australian Standards for specific matters.

In this manner, Standards Australia forms a self-referring ecosystem.

R2A understands that this is done as a matter of policy. There are good technical and business reasons for this approach;

- First, some quality assurance of content and minimising repetition of content, and

- Second, to keep intellectual property and revenue in-house.

However, this hall of mirrors can lead to initially small issues propagating through the ecosystem.

At this point, it is worth asking what a standard actually is.

In short, a standard is a documented assembly of recognised good practice.

What is recognised good practice?

Measures which are demonstrably reasonable by virtue of others spending their resources on them in similar situations. That is, to address similar risks.

But note: the ideas contained in the standard are the good practice, not the standard itself.

And what are standards for?

Standards have a number of aims. Two of the most important being to:

- Help people to make decisions, and

- Help people to not make decisions.

That is, standards help people predict and manage the future – people such as engineers, designers, builders, and manufacturers.

When helping people not make decisions, standards provide standard requirements, for example for design parameters. These standards have already made decisions so they don’t need to be made again (for example, the material and strength of a pipe necessary for a certain operating pressure). These are one type of standard.

The other type of standard helps people make decisions. They provide standardised decision-making processes for applications, including asset management, risk management, quality assurance and so on.

Such decision-making processes are not exclusive to Australian Standards.

One of the more important of these is the process to demonstrate due diligence in decision-making – that is that all reasonable steps were taken to prevent adverse outcomes.

This process is of particular relevance to engineers, designers, builders, manufacturers etc., as adverse events can often result in safety consequences.

A diligent safety decision-making process involves,:

- First, an argument as to why no credible, critical issues have been overlooked,

- Second, identification of all practicable measures that may be implemented to address identified issues,

- Third, determination of which of these measures are reasonable, and

- Finally, implementation of the reasonable measures.

This addresses the legal obligations of engineers etc. under Australian work health and safety legislation.

Standards fit within this due diligence process as examples of recognised good practice.

They help identify practicable options (the second step) and the help in determining the reasonableness of these measures for the particular issues at hand. Noting the two types of standards above, these measures can be physical or process-based (e.g. decision-making processes).

Each type of standard provides valuable guidance to those referring to it. However the combination of the self-referring standards ecosystem and the two types of standards leads to some perhaps unintended consequences.

Some of these arise in AS2885.

One of the main goals of AS2885 is the safe operation of pipelines containing gas or liquid petroleum; the draft AS2885:2017 presents the standard's latest thinking.

As part of this it sets out the following process.

- Determine if a particular safety threat to a pipeline is credible.

- Then, implement some combination of physical and procedural controls.

- Finally, look at the acceptability of the residual risk as per the process set out in AS31000, the risk management standard, using a risk matrix provided in AS2885.

If the risk is not acceptable, apply more controls until it is and then move on with the project. (See e.g. draft AS2885.6:2017 Appendix B Figures B1 Pipeline Safety Management Process Flowchart and B2 Whole of Life Pipeline Safety Management.)

But compare this to the decision-making process outlined above, the one needed to meet WHS legislation requirements. It is clear that this process has been hijacked at some point – specifically at the point of deciding how safe is safe enough to proceed.

In the WHS-based process, this decision is made when there are no further reasonable control options to implement. In the AS2885 process the decision is made when enough controls are in place that a specified target level of risk is no longer exceeded.

The latter process is problematic when viewed in hindsight. For example, when viewed by a court after a safety incident.

In hindsight the courts (and society) actually don’t care about the level of risk prior to an event, much less whether it met any pre-determined subjective criteria.

They only care whether there were any control options that weren’t in place that reasonably ought to have been.

‘Reasonably’ in this context involves consideration of the magnitude of the risk, and the expense and difficulty of implementing the control options, as well as any competing responsibilities the responsible party may have.

The AS2885 risk sign-off process does not adequately address this. (To read more about the philosophical differences in the due diligence vs. acceptable risk approaches, see here.)

To take an extreme example, a literal reading of the AS2885.6 process implies that it is satisfactory to sign-off on a risk presenting a low but credible chance of a person receiving life-threatening injuries by putting a management plan in place, without testing for any further reasonable precautions.[1]

In this way AS2885 moves away from simply presenting recognised good practice design decisions as part of a diligent decision-making process and, instead, hijacks the decision-making process itself.

In doing so, it mixes recognised good practice design measures (i.e. reasonable decisions already made) with standardised decision-making processes (i.e. the AS31000 risk management approach) in a manner that does not satisfy the requirements of work health and safety legislation. The draft AS2885.6:2017 appears to realise this, noting that “it is not intended that a low or negligible risk rank means that further risk reduction is unnecessary”.

And, of course, people generally don’t behave quite like this when confronted with design safety risks.

If they understand the risk they are facing they usually put precautions in place until they feel comfortable that a credible, critical risk won’t happen on their watch, regardless of that risk’s ‘acceptability’.

That is, they follow the diligent decision-making process (albeit informally).

But, in that case, they are not actually following the standard.

This raises the question:

Is the risk decision-making element of AS2885 recognised good practice?

Our experience suggests it is not, and that while the good practice elements of AS2885 are valuable and must be considered in pipeline design, AS2885’s risk decision-making process should not.

[1] AS2885.6 Section 5: “... the risk associated with a threat is deemed ALARP if ... the residual risk is assessed to be Low or Negligible”

Consequences (Section 3 Table F1): Severe - “Injury or illness requiring hospital treatment”. Major: “One or two fatalities; or several people with life-threatening injuries”. So one person with life-threatening injuries = ‘Severe’?

Likelihood (Section 3 Table 3.2): “Credible”, but “Not anticipated for this pipeline at this location”,

Risk level (Section 3 Table 3.3): “Low”.

Required action (Section 3 Table 3.4): “Determine the management plan for the threat to prevent occurrence and to monitor changes that could affect the classification”.

Risk Engineering Body of Knowledge

Engineers Australia with the support of the Risk Engineering Society have embarked on a project to develop a Risk Engineering Book of Knowledge (REBoK). Register to join the community.

The first REBoK session, delivered by Warren Black, considered the domain of risk and risk engineering in the context risk management generally. It described the commonly available processes and the way they were used.

Following the initial presentation, Warren was joined by R2A Partner, Richard Robinson and Peter Flanagan to answer participant questions. Richard was asked to (again) explain the difference between ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) and SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable).

The difference between ALARP and SFAIRP and due diligence is a topic we have written about a number of times over the years. As there continues to be confusion around the topic, we thought it would be useful to link directly to each of our article topics.

Does ALARP equal due diligence, written August 2012

Does ALARP equal due diligence (expanded), written September 2012

Due Diligence and ALARP: Are they the same?, written October 2012

SFAIRP is not equivalent to ALARP, written January 2014

When does SFAIRP equal ALARP, written February 2016

Future REBoK sessions will examine how the risk process may or may not demonstrate due diligence.

Due diligence is a legal concept, not a scientific or engineering one. But it has become the central determinant of how engineering decisions are judged, particularly in hindsight in court.

It is endemic in Australian law including corporations law (eg don’t trade whilst insolvent), safety law (eg WHS obligations) and environmental legislation as well as being a defence against (professional) negligence in the common law.

From a design viewpoint, viable options to be evaluated must satisfy the laws of nature in a way that satisfies the laws of man. As the processes used by the courts to test such options forensically are logical and systematic and readily understood by engineers, it seems curious that they are not more often used, particularly since it is a vital concern of senior decision makers.

Stay tuned for further details about upcoming sessions. And if you are needing clarification around risk, risk engineering and risk management, contact us for a friendly chat.

Rights vs Responsibilities in Due Diligence

A recent conversation with a consultant to a large law firm described the current legal trend in Melbourne, notably that rights had become more important than responsibilities.This certainly seems to be the case for commercial entities protecting sources of income, as particularly evidenced in the current banking Royal Commission (Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry).It seems that, in the provision of financial advice, protecting consulting advice cash flow was seen as much more important than actually providing the service.Engineers probably have a reverse perspective. As engineers deal with the real (natural material) world, poor advice is often very obvious. When something fails unexpectedly, death and injury are quite likely.Just consider the Grenfell Tower fire in London and the Lacrosse fire in Melbourne. This means that for engineers at least, responsibilities often overshadow rights.This is a long standing, well known issue. For example, the old ACEA (Association of Consulting Engineers, Australia) used to require that at least 50% of the shares of member firms were owned by engineers who were members in good standing of Engineers Australia (FIEAust or MIEAust) and thereby bound by Engineers Australia’s Code of Ethics.The point was to ensure that, in the event of a commission going badly, the majority of the board would abide by the Code of Ethics and look after the interests of the client ahead of the interests of the shareholders.Responsibilities to clients were seen to be more important than shareholder rights, a concept which appears to be central to the notion of trust.