Why SFAIRP is not a safety risk assessment

Weaning boards off the term risk assessment is difficult.

Even using the term implies that there must be some minimum level of ‘acceptable safety’.

And in one sense, that’s probably the case once the legal idea of ‘prohibitively dangerous’ is invoked.

But that’s a pathological position to take if the only reason why you’re not going to do something is because if it did happen criminal manslaughter proceedings are a likely prospect.

SFAIRP (so far is as reasonably practicable) is fundamentally a design review. It’s about the process.

The meaning is in the method, the results are only consequences.

In principle, nothing is dangerous if sufficient precautions are in place.

Flying in jet aircraft, when it goes badly, has terrible consequences. But with sufficient precautions, it is fine, even though the potential to go badly is always present. But no one would fly if the go, no-go decision was on the edge of the legal concept of ‘prohibitively dangerous’.

We try to do better than that. In fact, we try to achieve the highest level of safety that is reasonably practicable. This is the SFAIRP position. And designers do it because it has always been the sensible and right thing to do.

The fact that it has also been endorsed by our parliaments to make those who are not immediately involved in the design process, but who receive (financial) rewards from the outcomes, accountable for preventing or failing to let the design process be diligent is not the point.

How do you make sure the highest reasonable level of protection is in place? The answer is you conduct a design review using optimal processes which will provide for optimal outcomes.

For example, functional safety assessment using the principle of reciprocity (Boeing should have told pilots about the MCAS in the 737 MAX) supported by the common law hierarchy of control (elimination, prevention and mitigation). And you transparently demonstrate this to all those who want to know via a safety case in the same way a business case is put to investors.

But the one thing SFAIRP isn’t, is a safety risk assessment. Therein lies the perdition.

Does Safety & Risk Management need to be Complicated?

With Engineer’s Australia recent call-out on socials for "I Am An Engineer" stories, I was discussing career accomplishments with a team member (non-Engineer) and we were struck by how risk and safety need not be complicated – that the business of risk and safety, especially in assessment terms has been over-complicated.

Two such career accomplishments that really brought this home was my due diligence engineering work on:

- Gateway Bridge in Brisbane

Our recommendation was rather than implement a complicated IT information system on the bridge for traffic hazards associated with wind, to install a windsock or flag and let the wind literally show its strength and direction in real time. A simple but effective control that ensures no misinformation. - Victorian Regional Rail Level Crossings

R2A assessed every rail level crossing in the four regional fast rail corridors in Victoria for the requirements to operate faster running trains. The simple conclusion, that I know saved countless lives, was to recommend closing level crossings where possible or provide active crossings (bells and flashing lights) rather than passive level crossings.

However, some risk and safety issues are not as simple, like women’s PPE.

The simple solution, to date, has been for women to wear downsized men’s PPE and workwear. But we know this is not the safest solution because women’s body shapes are completely different to men.

My work with Apto PPE has been about designing workwear from a due diligence engineering perspective. This amounted to the need to design from a clean slate (pattern, should I say!) -- designing for women’s body shapes from the outset and not tweaking men's designs.

Not everyone does this in the workwear sector, but as an engineer, I understand the importance of solving problems effectively and So Far As Is Reasonably Practicable (SFAIRP).

By applying the SFAIRP principle, you are really asking the question, if I was in the same position, how would I expect to be treated and what controls would I expect to be in place, which is usually not a complicated question.

And, maybe, my biggest career accomplishment will be the legacy work with R2A and Apto PPE in making a difference to how people think about and conduct safety and due diligence in society.

Find out more about Apto PPE, head to aptoppe.com.au

To speak with Gaye about due diligence and/or Apto PPE, head to the contact page.

Why Risk changed to Due Diligence & Why it’s become so Important

At our April launch of the 11th Edition of Engineering Due Diligence textbook, I discussed how the service of Risk Reviews has changed to Due Diligence and why it’s become so important for Australian organisations.

But to start, I need to go back to 1996. The R2A team and I were conducting risk reviews on large scale engineering projects, such as double deck suburban trains and traction interlocking in NSW, and why the power lines in Tasmania didn't need to comply with CB1 & AS7000, and why the risk management standard didn't work in these situations.And, what we kept finding was that as engineers we talked about high consequence, low likelihood (rare) events, and then we’d argue the case with the financial people over the cost of precautions we suggested should be in place, we’d always lose the argument.However, when lawyers were standing with us saying, 'what the engineers are saying makes sense - it's a good idea', then the ‘force’ was with us and what we as engineers suggested was done.

As a result, in the 2000s we started flipping the process around and would lead with the legal argument first and then support this with the engineering argument. And every time we did that, we won.

It was at this stage we started changing from Risk and Reliability to Due Diligence Engineers, because it was always necessary to run with the due diligence first to make our case.

Since we made this fundamental change in service and became more involved in delivering high level work, that is, due diligence, it has also become part of the Australian governance framework.Due diligence has become endemic in Australian legislation. In corporations’ law; directors must demonstrate diligence to ensure, for example, that a business pays its bills when they fall due. It's in WHS Legislation. It's in Environmental Legislation. Due diligence is now required to demonstrate good corporate governance.And what I mean by that is that there’s a swirl of ideas that run around our parliaments. Our politicians pick the ideas they think are good ones. One of these was the notion of due diligence that was picked up from the judicial, case (common) law system.There’s an interesting legal case on the topic going back to 1932: Donoghue vs Stevenson; the Snail in the Bottle. When making his decision, the Brisbane-born English law lord, Lord Aitken said that the principle to adopt is; do unto others as you would have done unto you.The do unto others principle (the principle of reciprocity) was nothing new; it’s been a part of major philosophies and religions for over 2000 years.Our parliamentarians took the do unto others idea and incorporated it into Acts, Regulations and Codes of Practice as the notion of Due Diligence.That is, due diligence has become endemic in Australian legislation and in case law, to the point that it has become, in the philosopher Immanuel Kant’s terms, a categorical imperative. That is, our parliamentarians and judges seem to have decided that due diligence is universal in its application and creates a moral justification for action. This also means the converse, that failure to act demands sanction against the failed decision maker. I discuss this further along with two examples in the article What are the Unintended Consequences of Due Diligence.To learn more about Engineering Due Diligence and the tools we teach at our two-day workshop, you can purchase our text resource here.If you’d like to discuss we can help you make diligent decisions that are safe, effective and compliant, we’d love to hear from you. Contact us today.

Worse Case Scenario versus Risk & Combustible Cladding on Buildings

BackgroundThe start of 2019 has seen much media attention to various incidents resulting from, arguably, negligent decision making.One such incident was the recent high-rise apartment building fire in Melbourne that resulted in hundreds of residents evacuated.The fire is believed to have started due to a discarded cigarette on a balcony and quickly spread five storeys. The Melbourne Fire Brigade said it was due to the building’s non-combustible cladding exterior that allowed the fire to spread upwards. The spokesperson also stated the cladding should not have been permitted as buildings higher than three storeys required a non-combustible exterior.Yet, the Victorian Building Authority did inspect and approve the building.Similar combustible cladding material was also responsible for another Melbourne based (Docklands) apartment building fire in 2014 and for the devastating Grenfell Tower fire in London in 2017 that killed 72 people with another 70 injured.This cladding material (and similar) is wide-spread across high-rise buildings across Australia. Following the Docklands’ building fire, a Victorian Cladding Task Force was established to investigate and address the use of non-compliant building materials on Victorian buildings.Is considering Worse Case Scenario versus Risk appropriate?In a television interview discussing the most recent incident, a spokesperson representing Owners’ Corporations stated owners needed to look at worse case scenarios versus risk. He followed the statement with “no one actually died”.While we agree risk doesn’t work for high consequence, low likelihood events, responsible persons need to demonstrate due diligence for the management of credible critical issues.The full suite of precautions needs to be looked at for a due diligence argument following the hierarchy of controls.The fact that no one died in either of the Melbourne fires can be attributed to Australia’s mandatory requirement of sprinklers in high rise buildings. This means the fires didn’t penetrate the building. However, the elimination of cladding still needs to be tested from a due diligence perspective consistent with the requirements of Victoria’s OHS legislation.What happens now?The big question, beyond that of safety, is whether the onus to fix the problem and remove / replace the cladding is now on owners at their cost or will the legal system find construction companies liable due to not demonstrating due diligence as part of a safety in design process?Residents of the Docklands’ high-rise building decided to take the builder, surveyor, architect, fire engineers and other consultants to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) after being told they were liable for the flammable cladding.Defence for the builder centred around evidence of how prevalent the cladding is within Australian high-rise buildings.The architect’s defence was they simply designed the building.The surveyor passed the blame onto the Owners’ Corporation for lack of inspections of balconies (where the fire started, like the most recent fire, with a discarded cigarette).Last week (at the time of writing), the apartment owners were awarded damages for replacement of the cladding, property damages from the fire and an increase in insurance premiums due to risk of future incidents. In turn, the architect, fire engineer and building surveyor have been ordered to reimburse the builder most of the costs.Findings by the judge included the architect not resolving issues in design that allowed extensive use of the cladding, a failure of “due care” by the building surveyor in its issue of building permit, and failure of fire engineer to warn the builder the proposed cladding did not comply with Australian building standards.Three percent of costs were attributed to the resident who started the fire.Does this ruling set precedence?Whilst other Owners’ Corporations may see this ruling as an opportunity (or back up) to resolve their non-compliant cladding issues, the Judge stated they should not see it as setting any precedent.

"Many of my findings have been informed by the particular contracts between the parties in this case and by events occurring in the course of the Lacrosse project that may or may not be duplicated in other building projects," said Judge Woodward.

If you'd like to discuss how conducting due diligence from an engineering perspective helps make diligent decisions that are effective, safe and compliant, contact us for a chat.

Why your team has a duty of care to show they've been duly diligent

In October and November (2018), I presented due diligence concepts at four conferences: The Chemeca Conference in Queenstown, the ISPO (International Standard for maritime Pilot Organizations) conference in Brisbane, the Australian Airports Association conference in Brisbane (with Phil Shaw of Avisure) and the NZ Maritime Pilots conference in Wellington.

The last had the greatest representation of overseas presenters. In particular, Antonio Di Lieto, a senior instructor at CSMART, Carnival Corporation's Cruise ship simulation centre in the Netherlands. He mentioned that:

a recent judgment in Italian courts had reinforced the paramountcy of the due diligence approach but in this instance within the civil law, inquisitorial legal system.

This is something of a surprise. R2A has previously attempted to test ‘due diligence’ in the European civil (inquisitorial) legal system over a long period by presenting papers at various conferences in Europe. The result was usually silence or some comment about the English common law peculiarities.

The aftermath of the accident at the port of Genoa. Credit: PA

The incident in question occurred on May 2013. While executing the manoeuvre to exit the port of Genoa, the engine of the cargo ship “Jolly Nero” went dead. The big ship smashed into the Control Tower, destroying it, and causing the death of nine people and injuring four.

So far the ship’s master, first officer and chief engineer have all received substantial jail terms, as has the Genoa port pilot. It seems that a failure to demonstrate due diligence secured these convictions

And there are two more ongoing inquiries:

- One regards the construction of the Tower in that particular location, an investigation that has already produced two indictments; and

- The second that focuses on certain naval inspectors that certified ship.

It's important to realise everyone involved -- the bridge crew, the ship’s engineer, ship certifier, marine pilot, and the port designer -- all have a duty of care that requires, post event, they had been duly diligent.

Are you confident in your team's diligent decision making? If not, R2A can help; contact us to discuss how.

What you can learn about Organisational Risk Culture from the CBA Prudential Inquiry

R2A was recently commissioned to complete a desktop risk documentation review in the context of the CBA Prudential Inquiry of 2018. The review has provided a framework for boards across all sectors to consider the strength of their risk culture. This has been bolstered by the revelations from The Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry.

Specifically, R2A was asked to provide commentary on the following:

- Overall impressions of the risk culture based on the documentation.

- To what extent the documents indicate that the organisation uses organisational culture as a risk tool.

- Any obvious flaws, omissions or areas for improvement

- Other areas of focus (or questions) suggested for interviews with directors, executives and managers as part of an organisational survey.

What are the elements of good organisational risk culture?

Organisations with a mature risk culture have a good understanding of risk processes and interactions. In psychologist James Reason’s terms[1], these organisations tend towards a generative risk culture shown in James Reason’ s table of safety risk culture below.

| Pathological culture | Bureaucratic culture | Generative culture |

|

|

|

How different organisational cultures handle safety information

Key attributes include:

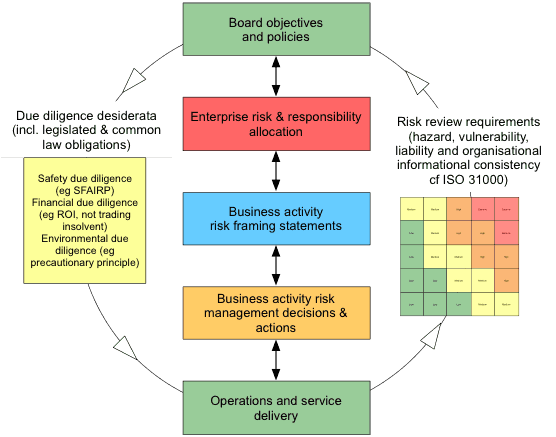

- Risk management should be embedded into everyday activities and be everyone’s responsibility with the Board actively involved in setting the risk framework and approving all risk policy. Organisations with a good risk culture have a strong interaction throughout the entire organisation from the Board and Executive Management levels right through to the customer interface.

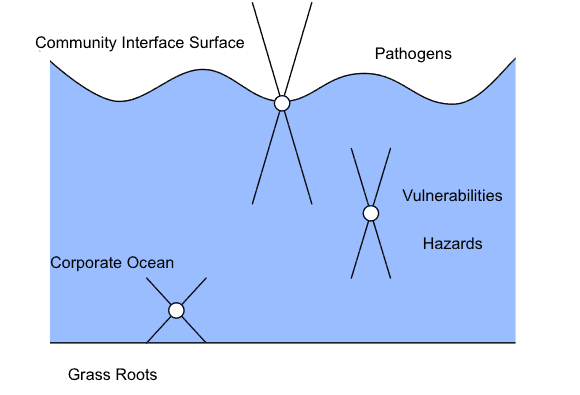

- The organisation has a formal test of risk ‘completeness’ to ensure that no credible critical risk issue has been overlooked. To achieve this, R2A typically use a military intelligence threat and vulnerability technique. The central concept is to define the organisation’s critical success outcomes (CSOs). Threats to those success outcomes are subsequently identified and are then systematically matched against the outcomes to identify critical vulnerabilities. Only the assessed vulnerabilities then have control efforts directed at them. This prevents the misapplication of resources to something that was really only a threat and not a vulnerability.

- Risk decision making is done using a due diligence approach. This means ensuring that all reasonable practicable precautions are in place to provide confidence that no critical organisational vulnerabilities remain. Due diligence is demonstrated based on the balance of the significance of the risk vs the effort required to achieve it (the common law balance). This is consistent with the due diligence provisions of the Corporations, Safety (OHS/WHS) and environmental legislation.

Risk frameworks and characterisation systems such as the popular 5x5 risk matrix (heat map) approach are good reporting tools to present information and should be used to support the risk management feedback process. Organisations should specifically avoid using ‘heatmaps’ as decision making tool as that is inconsistent with fiduciary, safety and environmental legislative requirements.

Risk Appetite Statements for commercial organisations have become very fashionable. The statement addresses the key risk areas for the business and usually considers both the possibility of risk and reward. However, for some elements such as compliance (zero tolerance) and safety (zero harm), risk appetite may be less appropriate as the consequences of failure are so high that there is simply no appetite for it. For this reason, R2A prefers the term risk position statements rather than risk appetite statements.

To get a feel for the risk culture within an organisation, R2A suggest conducting generative interviews with recognised organisational ‘good’ players rather than conducting an audit.

We consider generative interviews to be a top-down enquiry and judgement of unique organisations rather than a bottom-up audit for deficiencies and castigation of variations for like organisations. R2A believes that the objective is to delve sufficiently until evidence to sustain a judgement is transparently available to those who are concerned. (Enquiries should be positive and indicate future directions whereas audits are usually negative and suggest what ought not to be done).

Interview depth

Individuals have different levels of responsibility in any organisation. For example, some are firmly grounded with direct responsibility for service to members. Others work at the community interface surface with responsibilities that extend deep into the organisation as well as high into the community. We understand that the idea is that a team interviews recognised 'good players' at each level of the organisation. If a commonality of problems and, more particularly, solutions are identified consistently from individuals at all levels, then adopting such solutions would be fast, reliable and very, very desirable.

Other positive feedback loops may be created too. The process should be stimulating, educational and constructive. Good ideas from other parts of the organisation ought to be explained and views as to the desirability of implementation in other places sought.

If a health check on your organsational risk culture or a high level review of your enterprise risk management system is of interest, please give us a call to discuss further on 1300 772 333 or head to our contact page and fill in an enquiry.

[1] Reason, J., 1997. Managing the Risks of Organisational Accidents. Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited. Page 38.

Managing Critical Risk Issues: Synthesising Liability Management with the Risk Management Standard

The importance of organisations managing critical risk issues has been highlighted recently with the opening hearings of the coronial inquest into the 2016 Dreamworld Thunder River Rapids ride tragedy that killed four people.

In a volatile world, boards and management fret that some critical risk issues are neither identified nor managed effectively, creating organisational disharmony and personal liabilities for senior decision makers.

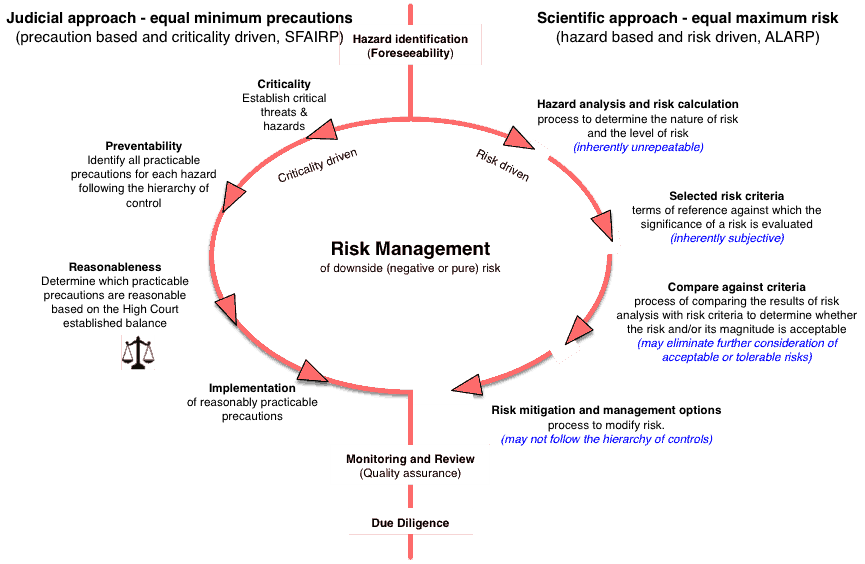

The obligations of WHS – OHS precaution based legislation conflict with the hazard based Risk Management Standard (ISO 31000) that most corporates and governments in Australia mandate. This is creating very serious confusion, particularly with the understanding of economic regulators.

The table below summarises the two approaches.

| Precaution-based Due Diligence (SFAIRP) | ≠ | Hazard-based Risk Management (ALARP) | |

| Precaution focussed by testing all practicableprecautions for reasonableness. | Hazard focussed by comparison to acceptable ortolerable target levels of risk. | ||

| Establish the context

Risk assessment (precaution based): Identify credible, critical issues Identify precautionary options Risk-effort balance evaluation Risk action (treatment) |

Establish the context Risk assessment (hazard based): (Hazard) risk identification (Hazard) risk analysis (Hazard) risk evaluation Risk treatment |

||

| Criticality driven. Normal interpretation ofWHS (OHS) legislation & common law |

Risk (likelihood and consequence) driven Usual interpretation of AS/NZS ISO 31000[1] |

||

A paradigm shift from hazard to precaution based risk assessment

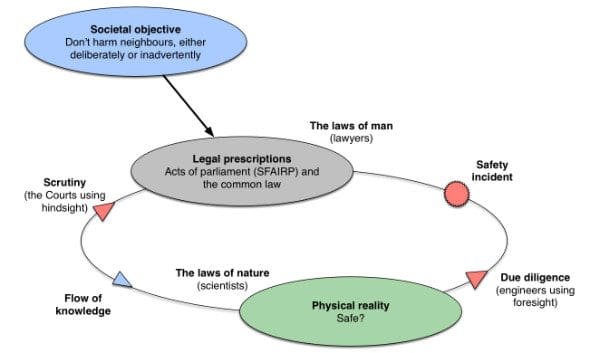

Decision making using the hazard based approach has never satisfied common law judicial scrutiny. The diagram below shows the difference between the two approaches. The left hand side of the loop describes the legal approach which results in risk being eliminated or minimised so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP) such as described in the model WHS legislation.

Its purpose is to demonstrate that all reasonable practicable precautions are in place by firstly identifying all possible practicable precautions and then testing which are reasonableness in the circumstances using relevant case law.

The level of risk resulting from this process might be as low as reasonably practicable (ALARP) but that’s not the test that’s applied by the courts after the event. The courts test for the level of precautions, not the level of risk. The SFAIRP concept embodies this outcome.

The target risk approach, shown on the right hand side, attempts to demonstrate that an acceptable risk level associated with the hazard has been achieved, often described as as low as reasonably practicable or ALARP. But there are major difficulties with each step of this approach as noted in blue.

SFAIRP v ALARP

However, there is a way forward that usefully synthesises the two approaches, thereby retaining the existing ISO 31000 reporting structure whilst ensuring a defensible decision making process.

Essentially, high consequence, low likelihood risk decisions are based on due diligence (for example, SFAIRP, ROI, not trading whilst insolvent and the precautionary principle, consistent with the decisions of the High Court of Australia) whilst risk reporting is done via the Risk Management Standard using risk levels, heat maps and the like. This also resolves the tension between the use of the concepts of ‘risk appetite’ (very useful for commercial decisions) and ‘zero harm’ (meaning no appetite for inadvertent deaths).

Essentially the approach threads the work completed (often) in silos by field / project staff into a consolidated framework for boards and executive management.

If you'd like to discuss how we can assist with identifying and managing critical risk issues within your organisation, we'd love to hear from you. Head to our contact page to organise a friendly chat.

[1] From the definition in AS/NZS ISO 31000: 2.24 risk evaluation process of comparing the results of risk analysis (2.21) with risk criteria (2.22) to determine whether the risk (2.1) and/or its magnitude is acceptable or tolerable.

Australian Standard 2885, Pipeline Safety & Recognised Good Practice

Australian guidance for gas and liquid petroleum pipeline design guidance comes, to a large extent, from Australian Standard 2885. Amongst other things AS2885 Pipelines – Gas and liquid petroleum sets out a method for ensuring these pipelines are designed to be safe.

Like many technical standards, AS2885 provides extensive and detailed instruction on its subject matter. Together, its six sub-titles (AS2885.0 through to AS2885.5) total over 700 pages. AS2885.6:2017 Pipeline Safety Management is currently in draft and will likely increase this number.

In addition, the AS2885 suite refers to dozens of other Australian Standards for specific matters.

In this manner, Standards Australia forms a self-referring ecosystem.

R2A understands that this is done as a matter of policy. There are good technical and business reasons for this approach;

- First, some quality assurance of content and minimising repetition of content, and

- Second, to keep intellectual property and revenue in-house.

However, this hall of mirrors can lead to initially small issues propagating through the ecosystem.

At this point, it is worth asking what a standard actually is.

In short, a standard is a documented assembly of recognised good practice.

What is recognised good practice?

Measures which are demonstrably reasonable by virtue of others spending their resources on them in similar situations. That is, to address similar risks.

But note: the ideas contained in the standard are the good practice, not the standard itself.

And what are standards for?

Standards have a number of aims. Two of the most important being to:

- Help people to make decisions, and

- Help people to not make decisions.

That is, standards help people predict and manage the future – people such as engineers, designers, builders, and manufacturers.

When helping people not make decisions, standards provide standard requirements, for example for design parameters. These standards have already made decisions so they don’t need to be made again (for example, the material and strength of a pipe necessary for a certain operating pressure). These are one type of standard.

The other type of standard helps people make decisions. They provide standardised decision-making processes for applications, including asset management, risk management, quality assurance and so on.

Such decision-making processes are not exclusive to Australian Standards.

One of the more important of these is the process to demonstrate due diligence in decision-making – that is that all reasonable steps were taken to prevent adverse outcomes.

This process is of particular relevance to engineers, designers, builders, manufacturers etc., as adverse events can often result in safety consequences.

A diligent safety decision-making process involves,:

- First, an argument as to why no credible, critical issues have been overlooked,

- Second, identification of all practicable measures that may be implemented to address identified issues,

- Third, determination of which of these measures are reasonable, and

- Finally, implementation of the reasonable measures.

This addresses the legal obligations of engineers etc. under Australian work health and safety legislation.

Standards fit within this due diligence process as examples of recognised good practice.

They help identify practicable options (the second step) and the help in determining the reasonableness of these measures for the particular issues at hand. Noting the two types of standards above, these measures can be physical or process-based (e.g. decision-making processes).

Each type of standard provides valuable guidance to those referring to it. However the combination of the self-referring standards ecosystem and the two types of standards leads to some perhaps unintended consequences.

Some of these arise in AS2885.

One of the main goals of AS2885 is the safe operation of pipelines containing gas or liquid petroleum; the draft AS2885:2017 presents the standard's latest thinking.

As part of this it sets out the following process.

- Determine if a particular safety threat to a pipeline is credible.

- Then, implement some combination of physical and procedural controls.

- Finally, look at the acceptability of the residual risk as per the process set out in AS31000, the risk management standard, using a risk matrix provided in AS2885.

If the risk is not acceptable, apply more controls until it is and then move on with the project. (See e.g. draft AS2885.6:2017 Appendix B Figures B1 Pipeline Safety Management Process Flowchart and B2 Whole of Life Pipeline Safety Management.)

But compare this to the decision-making process outlined above, the one needed to meet WHS legislation requirements. It is clear that this process has been hijacked at some point – specifically at the point of deciding how safe is safe enough to proceed.

In the WHS-based process, this decision is made when there are no further reasonable control options to implement. In the AS2885 process the decision is made when enough controls are in place that a specified target level of risk is no longer exceeded.

The latter process is problematic when viewed in hindsight. For example, when viewed by a court after a safety incident.

In hindsight the courts (and society) actually don’t care about the level of risk prior to an event, much less whether it met any pre-determined subjective criteria.

They only care whether there were any control options that weren’t in place that reasonably ought to have been.

‘Reasonably’ in this context involves consideration of the magnitude of the risk, and the expense and difficulty of implementing the control options, as well as any competing responsibilities the responsible party may have.

The AS2885 risk sign-off process does not adequately address this. (To read more about the philosophical differences in the due diligence vs. acceptable risk approaches, see here.)

To take an extreme example, a literal reading of the AS2885.6 process implies that it is satisfactory to sign-off on a risk presenting a low but credible chance of a person receiving life-threatening injuries by putting a management plan in place, without testing for any further reasonable precautions.[1]

In this way AS2885 moves away from simply presenting recognised good practice design decisions as part of a diligent decision-making process and, instead, hijacks the decision-making process itself.

In doing so, it mixes recognised good practice design measures (i.e. reasonable decisions already made) with standardised decision-making processes (i.e. the AS31000 risk management approach) in a manner that does not satisfy the requirements of work health and safety legislation. The draft AS2885.6:2017 appears to realise this, noting that “it is not intended that a low or negligible risk rank means that further risk reduction is unnecessary”.

And, of course, people generally don’t behave quite like this when confronted with design safety risks.

If they understand the risk they are facing they usually put precautions in place until they feel comfortable that a credible, critical risk won’t happen on their watch, regardless of that risk’s ‘acceptability’.

That is, they follow the diligent decision-making process (albeit informally).

But, in that case, they are not actually following the standard.

This raises the question:

Is the risk decision-making element of AS2885 recognised good practice?

Our experience suggests it is not, and that while the good practice elements of AS2885 are valuable and must be considered in pipeline design, AS2885’s risk decision-making process should not.

[1] AS2885.6 Section 5: “... the risk associated with a threat is deemed ALARP if ... the residual risk is assessed to be Low or Negligible”

Consequences (Section 3 Table F1): Severe - “Injury or illness requiring hospital treatment”. Major: “One or two fatalities; or several people with life-threatening injuries”. So one person with life-threatening injuries = ‘Severe’?

Likelihood (Section 3 Table 3.2): “Credible”, but “Not anticipated for this pipeline at this location”,

Risk level (Section 3 Table 3.3): “Low”.

Required action (Section 3 Table 3.4): “Determine the management plan for the threat to prevent occurrence and to monitor changes that could affect the classification”.

Risk Engineering Body of Knowledge

Engineers Australia with the support of the Risk Engineering Society have embarked on a project to develop a Risk Engineering Book of Knowledge (REBoK). Register to join the community.

The first REBoK session, delivered by Warren Black, considered the domain of risk and risk engineering in the context risk management generally. It described the commonly available processes and the way they were used.

Following the initial presentation, Warren was joined by R2A Partner, Richard Robinson and Peter Flanagan to answer participant questions. Richard was asked to (again) explain the difference between ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) and SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable).

The difference between ALARP and SFAIRP and due diligence is a topic we have written about a number of times over the years. As there continues to be confusion around the topic, we thought it would be useful to link directly to each of our article topics.

Does ALARP equal due diligence, written August 2012

Does ALARP equal due diligence (expanded), written September 2012

Due Diligence and ALARP: Are they the same?, written October 2012

SFAIRP is not equivalent to ALARP, written January 2014

When does SFAIRP equal ALARP, written February 2016

Future REBoK sessions will examine how the risk process may or may not demonstrate due diligence.

Due diligence is a legal concept, not a scientific or engineering one. But it has become the central determinant of how engineering decisions are judged, particularly in hindsight in court.

It is endemic in Australian law including corporations law (eg don’t trade whilst insolvent), safety law (eg WHS obligations) and environmental legislation as well as being a defence against (professional) negligence in the common law.

From a design viewpoint, viable options to be evaluated must satisfy the laws of nature in a way that satisfies the laws of man. As the processes used by the courts to test such options forensically are logical and systematic and readily understood by engineers, it seems curious that they are not more often used, particularly since it is a vital concern of senior decision makers.

Stay tuned for further details about upcoming sessions. And if you are needing clarification around risk, risk engineering and risk management, contact us for a friendly chat.

Rights vs Responsibilities in Due Diligence

A recent conversation with a consultant to a large law firm described the current legal trend in Melbourne, notably that rights had become more important than responsibilities.This certainly seems to be the case for commercial entities protecting sources of income, as particularly evidenced in the current banking Royal Commission (Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry).It seems that, in the provision of financial advice, protecting consulting advice cash flow was seen as much more important than actually providing the service.Engineers probably have a reverse perspective. As engineers deal with the real (natural material) world, poor advice is often very obvious. When something fails unexpectedly, death and injury are quite likely.Just consider the Grenfell Tower fire in London and the Lacrosse fire in Melbourne. This means that for engineers at least, responsibilities often overshadow rights.This is a long standing, well known issue. For example, the old ACEA (Association of Consulting Engineers, Australia) used to require that at least 50% of the shares of member firms were owned by engineers who were members in good standing of Engineers Australia (FIEAust or MIEAust) and thereby bound by Engineers Australia’s Code of Ethics.The point was to ensure that, in the event of a commission going badly, the majority of the board would abide by the Code of Ethics and look after the interests of the client ahead of the interests of the shareholders.Responsibilities to clients were seen to be more important than shareholder rights, a concept which appears to be central to the notion of trust.

Engineering As Law

Both law and engineering are practical rather than theoretical activities in the sense that their ultimate purpose is to change the state of the world rather than to merely understand it. The lawyers focus on social change whilst the engineers focus on physical change.It is the power to cause change that creates the ethical concerns. Knowing does not have a moral dimension, doing does. Mind you, just because you have the power to do something does not mean it ought to be done but conversely, without the power to do, you cannot choose.Generally for engineers, it must work, be useful and not harm others, that is, fit for purpose. The moral imperative arising form this approach for engineers generally articulated in Australia seems to be:

- S/he who pays you is your client (the employer is the client for employee engineers)

- Stick to your area of competence (don’t ignorantly take unreasonable chances with your client’s or employer’s interests)

- No kickbacks (don’t be corrupt and defraud your client or their customers)

- Be responsible for your own negligence (consulting engineers at least should have professional indemnity insurance)

- Give credit where credit is due (don’t pinch other peoples ideas).

Overall, these represent a restatement of the principle of reciprocity, that is, how you would be expected to be treated in similar circumstances and therefore becomes a statement of moral law as it applies to engineers.

How did it get to this? Project risk versus company liability

Disclosure: Tim Procter worked in Arup’s Melbourne office from 2008 until 2016.Shortly after Christmas a number of media outlets reported that tier one engineering consulting firm Arup had settled a major court case related to traffic forecasting services they provided for planning Brisbane’s Airport Link tunnel tollway. The Airport Link consortium sued Arup in 2014, when traffic volumes seven months after opening were less than 30% of that predicted. Over $2.2b in damages were sought; the settlement is reportedly more than $100m. Numerous other traffic forecasters on major Australian toll road projects have also faced litigation over traffic volumes drastically lower than those predicted prior to road openings.Studies and reviews have proposed various reasons for the large gaps between these predicted and actual traffic volumes on these projects. Suggested factors have included optimism bias by traffic forecasters, pressure by construction consortia for their traffic consultants to present best case scenarios in the consortia’s bids, and perverse incentives for traffic forecasters to increase the likelihood of projects proceeding past the feasibility stage with the goal of further engagements on the project.Of course, some modelling assumptions considered sound might simply turn out to be wrong – however, Arup’s lead traffic forecaster agreeing with the plaintiff’s lead counsel that the Airport Link traffic model was “totally and utterly absurd”, and that “no reasonable traffic forecaster would ever prepare” such a model indicates that something more significant than incorrect assumptions were to blame.Regardless, the presence of any one of these reasons would betray a fundamental misunderstanding of context by traffic forecasters. This misunderstanding involves the difference between risk and criticality, and how these two concepts must be addressed in projects and business.In Australia risk is most often thought of as the simultaneous appreciation of likelihood and consequence for a particular potential event. In business contexts the ‘consequence’ of an event may be positive or negative; that is, a potential event may lead to better or worse outcomes for the venture (for example, a gain or loss on an investment).In project contexts these potential consequences are mostly negative, as the majority of the positive events associated with the project are assumed to occur. From a client’s point of view these are the deliverables (infrastructure, content, services etc.) For a consultant such as a traffic forecaster the key positive event assumed is their fee (although they may consider the potential to make a smaller profit than expected).Likelihoods are then attached to these potential consequences to give a consistent prioritisation framework for resource allocation, normally known as a risk matrix. However, this approach does contain a blind spot. High consequence events (e.g. client litigation for negligence) are by their nature rare. If they were common it is unlikely many consultants would be in business at all. In general, the higher the potential consequence, the lower the likelihood.This means that potentially catastrophic events may be pushed down the priority list, as their risk (i.e. likelihood and consequence) level is low. And, although it may be very unlikely, small projects undertaken by small teams in large consulting firms may have the potential to severely impact the entire company. Traffic forecasting for proposed toll roads appears to be a case in point. As a proportion of income for a multinational engineering firm it may be minor, but from a liability perspective it is demonstrably critical, regardless of likelihood.There are a range of options available to organisations that wish to address these critical issues. For instance, a board may decide that if they wish to tender for a project that could credibly result in litigation for more than the organisation could afford, the project will not proceed unless the potential losses are lowered. This may be achieved by, for example, forming a joint venture with another organisation to share the risk of the tender.Identifying these critical issues, of course, relies on pre-tender reviews. These reviews must not only be done in the context of the project, but of the organisation as a whole. From a project perspective, spending more on delivering the project than will be received in fees (i.e. making a loss) would be considered critical. For the Board of a large organisation, a small number of loss-making projects each year may be considered likely, and, to an extent, tolerable. But the Board would likely consider a project with a credible chance, no matter how unlikely, of forcing the company into administration as unacceptable.This highlights the different perspectives at the various levels of large organisations, and the importance of clear communication of each of their requirements and responsibilities. If these paradigms are not understood and considered for each project tender, more companies may find themselves in positions they did not expect.Also published on:https://sourceable.net/how-did-it-get-to-this-project-risk-vs-company-liability/

Everyone is Entitled to Protection – But not Always the Same Level of Risk

When it comes to dealing with a known safety hazard, everyone is entitled to the same minimum level of protection.

This is the equity argument. It arises from Australia’s work health and safety legislation. It seems elementary. It is elementary. It has also, with the best intentions, been pushed aside by engineers for many years.

The 1974 UK Health and Safety at Work Act introduced the concept of “so far as is reasonably practicable” (SFAIRP) as a qualifier for duties set out in the Act. These duties required employers (and others) to ensure the health, safety and welfare of persons at work.

The SFAIRP principle, as it is now known, drew on the common law test of ‘reasonableness’ used in determining claims of negligence with regard to safety. This test was (and continues to be) developed over a long period of time through case law. In essence, it asks what a reasonable person would have done to address the situation in question.

One key finding elucidating the test is the UK’s Donoghue v. Stevenson (1932), also known as ‘the snail in the bottle’ case, which looked at what ‘proximity’ meant when considering who could be adversely affected by one’s actions.

Another is the UK’s Edwards v. National Coal Board (1949), in which the factors in determining what is ‘reasonably practicable’ were found to include the significance of the risk, and the time, difficulty and expense of potential precautions to address it.

These and other findings form a living, evolving understanding of what should be considered when determining the actions a reasonable person would take with regard to safety. They underpin the implementation of the SFAIRP principle in legislation.

And although in 1986 Australia and the UK formally severed all ties between their respective legislature and judiciary, both the High Court of Australia and Australia’s state and federal parliaments have retained and evolved the concepts of ‘reasonably practicable’ and SFAIRP in our unique context.

In determining what is ‘reasonable’ the Courts have the benefit of hindsight. The facts are present (though their meaning may be argued). Legislation, on the other hand, looks forward. It sets out what must be done, which if it is not done, will be considered an offence.

Legislating (i.e. laying down rules for the future) with regard to safety is difficult in this respect. The ways in which people can be damaged are essentially infinite. That people should try not to damage each other is universally accepted, but how could a universal moral principle against an infinite set of potential events be addressed in legislation?

Obviously not through prescription of specific safety measures (although this has been attempted in severely constrained contexts, for instance, specific tasks in particular industries). And given the complex and coincident factors involved in many safety incidents, how could responsibility for preventing this damage be assigned?

The most appropriate way to address this in legislation has been found, in different places and at different times, to be to invoke the test of reasonableness. That is, to qualify legislated duties for people to not damage each other with “so far as is reasonably practicable.”

This use of the SFAIRP principle in health and safety legislation, as far as it goes, has been successful. It has provided a clear and objective test, based on a long and evolving history of case law, for the judiciary to determine, after an event, if someone did what they reasonably ought to have done before the event to avoid the subsequent damage suffered by someone else. With the benefit of hindsight the Courts enjoy, this is generally fairly straightforward.

However, determining what is reasonable without this benefit - prior to an event - is more difficult. How should a person determine what is reasonable to address the (essentially infinite) ways in which their actions may damage others? And how could this be demonstrated to a court after an event?

Engineers, as a group, constantly make decisions affecting people’s safety. We do this in design, construction, operation, maintenance, and emergency situations. This significant responsibility is well understood, and safety considerations are paramount in any engineering activity. We want to make sure our engineering activities are safe. We want to make sure nothing goes wrong. And, if it does, we want to be able to explain ourselves. In short, we want to do it right. And if it goes wrong, we want to have an argument as to why we did all that was reasonable.

Some key elements of a defensible argument for reasonableness quickly present themselves. Such an argument should be systematic, not haphazard. It should, as far as possible, be objective. And through these considerations it should demonstrate equity, in that people are not unreasonably exposed to potential damage, or risk.

Engineers, being engineers, looked at these elements and thought: maths.

In 1988 the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) were at the forefront of this thinking. In the report of an extensive public inquiry into the proposed construction of the Sizewell B nuclear power plant the inquiry’s author, Sir Frank Layfield, made the recommendation that the HSE, as the UK’s statutory health and safety body, “should formulate and publish guidance on the tolerable levels of individual and social risk to workers and the public from nuclear power stations.”

This was a new approach to demonstrating equity with regards to exposure to risk. The HSE, in their 1988 study The Tolerability of Risk from Nuclear Power Stations, explored the concept. This review looked at what equity of risk exposure meant, how it might be demonstrated, and, critically, how mathematical and approaches could be used for this. It introduced the premise that everyone in (UK) society was constantly exposed to a ‘background’ level of risk which they were, if not comfortable with, at least willing to tolerate. This background risk was the accumulation of many varied sources, such as driving, work activities, house fires, lightning, and so on.

The HSE put forward the view that, firstly, there is a level of risk exposure individuals and society consider intolerable. Secondly, the HSE posited that there is a level of risk exposure that individuals and society consider broadly acceptable. Between these two limits, the HSE suggested that individuals and society would tolerate risk exposure, but would prefer for it to be lowered.

After identifying probabilities of fatality for a range of potential incidents, the HSE suggested boundaries between these ‘intolerable’, ‘tolerable’ and ‘broadly acceptable’ zones, the upper being risk of fatality of one in 10,000, and the lower being risk of fatality of one in 1,000,000.

The process of considering risk exposure and attempting to bring it within the tolerable or broadly acceptable zones was defined as reducing risk “as low as reasonably practicable,” or ALARP. This could be demonstrated through assessments of risk that showed that the numerical probability and/or consequence (i.e. resultant fatalities) of adverse events were lower than one or both of these limits. If these limits were not met, measures should be put in place until they were. And thus reducing risk ALARP would be demonstrated.

The ALARP approach spread quickly, with many new maths- and physics-based techniques being developed to better understand the probabilistic chains of potential events that could lead to different safety impacts. Over the subsequent 25 years, it expanded outside the safety domain.

Standards were developed using the ALARP approach as a basis, notably Australian Standard 4360, the principles of which were eventually brought into the international risk management standard ISO 31000 in 2009. This advocated the use of risk tolerability criteria for qualitative (i.e. non-mathematical, non-quantitative) risk assessments.

And from there, the ALARP approach spread through corporate governance, and became essentially synonymous with risk assessment as a whole, at least in Australia and the UK. It was held up as the best way to demonstrate that, if a safety risk or other undesired event manifested, decisions made prior to the event were reasonable.

But all was not well.

Consider again the characteristics of a defensible argument. It should be systematic, objective and demonstrate equity, in that people are not unreasonably exposed to risk.

Engineers have, by adopting the ALARP approach, attempted to build these arguments using maths, on the premise that, firstly, there are objective acceptable and intolerable levels of risk, as demonstrated by individual and societal behaviour, and, secondly, risk exposure within specific contexts (e.g. a workplace) could be quantified to these criteria. There are problems with mathematical rigour, which introduce subjectivity when quantifying risk in this manner, but on the whole these are seen as a deficit in technique rather than philosophy, and are generally considered solvable given enough time and computing power.

However, there is another way of constructing a defensible argument following the characteristics above.

Rather than focusing on the level of risk, the precautionary approach emphasises the level of protection against risk. For safety risks it does this by looking firstly at what precautions are in place in similar scenarios. These ‘recognised good practice’ precautions are held to be reasonable due to their implementation in existing comparable situations. Good practice may also be identified through industry standards, guidelines, codes of practice and so on.

The precautionary approach then looks at other precautionary options and considers on one hand the significance of the risk against, on the other, the difficulty, expense and utility of conduct required to implement and maintain each option. This is a type of cost-benefit assessment.

In practice, this means that if two parties with different resources face the same risk, they may be justified in implementing different precautions, but only if they have first implemented recognised good practice.

Critically, however, good practice is the ideas represented by these industry practices, standard, guidelines and so on, rather than the specific practices or the standards themselves. For example, implementing an inspection regime at a hazardous facility is unequivocally considered to be good practice. The frequency and level of detail required for inspection will vary depending on the facility and its particular context, but having no inspection regime at all is unacceptable.

The precautionary approach provides a formal, systematic, and objective safety decision-making alternative to the ALARP approach.

Equity with regard to safety can be judged in a number of ways. The ALARP approach considers equity of risk exposure. A second approach, generally used in legislation, addresses equity through eliminating exposure to specific hazards for particular groups of people, without regard to probability of occurrence. For example, dangerous goods transport is prohibited for most major Australian road tunnels regardless of how unlikely they may be to actually cause harm. In this manner, road tunnel users are provided equity in that none of them should be exposed to dangerous goods hazards in these tunnels.

The precautionary approach provides a third course. It examines equity inherent in the protection provided against particular hazards. It provides the three key characteristics in building a defensible argument for reasonableness.

It can be approached systematically, by first demonstrating identification and consideration of recognised good practice, and the decisions made for further options.

It is clearly objective, especially after an event; either the precautions were there or they were not.

And it considers equity in that for a known safety hazard, recognised good practice precautions are the absolute minimum that must be provided to protect all people exposed to the risk. Moving forward without good practice precautions in place is considered unacceptable, and would not provide equity to those exposed to the risk. While further precautions may be justified in particular situations, this will depend on the specific context, magnitude of the risk and the resources available.

Oddly enough, this is how the Courts view the world.

The Courts have trouble understanding the ALARP approach, especially in a safety context. From their point of view, once an issue is in front of them something has already gone wrong. Their role is then to objectively judge if a defendant’s (e.g. an engineer’s) decisions leading up to the event were reasonable.

Risk, in terms of likelihood and consequence, is no longer relevant; after an event the likelihood is certain, and the consequences have occurred. The Courts’ approach, in a very real sense, involves just two questions:

Was it reasonable to think this event could happen (and if not, why not)?Was there anything else reasonable that ought to have been in place that would have prevented these consequences?The ALARP approach is predicated on the objective assessment of risk prior to an event. However, after an event, the calculated probability of risk is very obviously called into question. This is especially so as the Courts tend to see low-likelihood high-consequence events.

If, using the ALARP approach, a safety risk was determined to have less than a one in 1,000,000 (i.e. ‘broadly acceptable’) likelihood of occurring, and then occurred shortly afterwards, serious doubt would be cast on the accuracy of the likelihood assessment.

But, more importantly, the Courts don’t take the level of risk into account in this way. It is simply not relevant to them. If a risk is assessed as ‘tolerable’ or ‘broadly acceptable’ the answer to the Courts’ first question above is obviously ‘yes’. The Courts’ second question then looks not at the level of risk in isolation, but at whether further reasonable precautions were available before the event.

‘Reasonable’ in an Australian legal safety context follows the 1949 UK Edwards v. National Coal Board definition and was refined by the High Court of Australia in Wyong Shire Council v. Shirt (1980). It requires that, when deciding on what to do about a safety risk, one must consider the options available and their reasonableness, not the level of risk in isolation. This is the requirement of the SFAIRP principle.

This firstly requires an understanding of whether options are reasonable by virtue of being recognised good practice. The reasonableness of further options can then be judged by considering the benefit (i.e. risk reduction) they could provide, as well as the costs required to implement them. Options judged as unreasonable on this basis may be rejected. It is only in this calculus that the level of risk (considered first in the ALARP approach) is considered by the Courts.

The ALARP approach does not meet this requirement. If a risk is determined to be ‘broadly acceptable’ then, by definition, risk equity is achieved, and no further precautions are required. But this may not satisfy the Courts’ requirement for equity of minimum protection from risk through recognised good practice precautions. It may also result in further reasonable options being dismissed.

The precautionary approach, on the other hand, specifically addresses the way in which the Courts determine if reasonable steps were taken, in a systematic, objective and equity-based manner. From a societal point of view, the Courts are our conscience. Making safety decisions consistent with how our Courts examine them would seem to be a responsible approach to engineering.

The ALARP approach was a good idea that didn’t work. With the best intentions, it was developed to its logical conclusions and was subsequently found to not meet society’s requirements as set forward by the Courts.

The precautionary approach’s recent prominence has been driven by the adoption of the SFAIRP principle in the National Model Work Health and Safety Act, now adopted in most Australian jurisdictions, followed by similar changes through the Rail Safety National Law, the upcoming Heavy Vehicle National Law and others. And as the common law principle of reasonableness finds it way into more legislation the need for an appropriate safety decision-making approach becomes paramount. It is an old idea made new, and it works. It provides equity.

Is there any good reason to not implement it?

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Tough Times Ahead for the Construction Sector?

The Construction Risk Management Summit organised by Expotrade was held in Melbourne on April 1 and 2, playing host to a diverse range of speakers and messages.

Possibly the most common message from academic speakers at the Construction Risk Management Summit was that the majority of projects do not come in on time or budget. In fact, many suffered from a major cost blowouts rate of nearly 100 per cent, with a wide array of reasons blamed for this issue.

The single biggest factor, which was identified by the majority of speakers, was failures in relation to upfront design. Typically, 80 per cent of the project cost is established at this phase. As a consequence, if errors occur during this phase of the project, additional expenses becomes a necessary, often quality controlled outcome. The solution to this issue was to have designers to focus on the long term operational performance, say at least 10 years operation, rather than just on practical completion.

This had several flow-on implications which were expanded upon by subsequent speakers. Knowing who the stakeholders are is critical. Stakeholders need to be understood and perhaps ranked in different ways, for example, as decision makers, interested parties and neighbours, lobby groups or as just acting in the public interest. This requires a culture of listening, which is an area the construction business should be encouraged to address.

Other speakers noted that the culture of the construction business could be changed, with safety in design identified as one cultural change that had occurred in recent times.

It was also noted that competitive pressures are still on the increase in the industry. Lowest tender bidding meant that corporate survival required "taking a chance" on contingencies in relation to risks that one could only hope would never eventuate.

If the construction market continues to shrink, more and more tenderers will be bidding for fewer and fewer jobs, with the final result being greater collective risk taking, or even an increasing likelihood of unethical behaviour.

This article first appeared on Sourceable. (No longer available)

Tough Times Ahead for Constructers?

Richard attended and presented at the recent Construction Risk Management Summit in Melbourne on 1stand 2nd April. It had a diverse range of speakers and messages.

Possibly the most common message from academic speakers was that the majority of projects do not come in on time or budget. In fact very many had major cost blowouts approaching 100%. There were a number of perceived reasons why this occurs.

Richard attended and presented at the recent Construction Risk Management Summit in Melbourne on 1st and 2nd April. It had a diverse range of speakers and messages.

Possibly the most common message from academic speakers was that the majority of projects do not come in on time or budget. In fact very many had major cost blowouts approaching 100%. There were a number of perceived reasons why this occurs.

The first, identified by the majority of speakers, focused on upfront design failures. Typically 80% of the project cost is established at this phase. So if this is wrong, such expense becomes a necessary, often quality ensued outcome. The solution to this issue was to get designers to focus on the long term operational performance, say at least 10 years operation, rather than just on practical completion.

The second related to competitive pressures which were increasing. Lowest tender bidding meant that corporate survival required taking a chance on contingencies for risks that might never eventuate. If the construction market continues to shrink, more and more tenderers will be bidding for fewer and fewer jobs and greater collective risk taking will result. One speaker even warned of an increasing likelihood of unethical behaviour in such circumstances.

Richard's presentation can be viewed on our conference page.

Sustainability Risk Management: (Legal) Due Diligence Obligations

Richard Robinson has been invited by Professor Tom Romberg to give a keynote address to the Engineers Australia Southern Highlands & Tablelands Regional Group for the Sydney Division Regional Convention 17-19 October 2014 in Bowral on the theme "Sustainability Risk Management".

Sustainability Risk Management focuses on environmental and social responsibility risks. US Professor Dan R Anderson observes that traditionally the costs associated with sustainability risk were externalised to the environment and general society. But increasingly they are being internalised to business.

Richard Robinson has been invited by Professor Tom Romberg to give a keynote address to the Engineers Australia Southern Highlands & Tablelands Regional Group for the Sydney Division Regional Convention 17-19 October 2014 in Bowral on the theme "Sustainability Risk Management".

Sustainability Risk Management focuses on environmental and social responsibility risks. US Professor Dan R Anderson observes that traditionally the costs associated with sustainability risk were externalised to the environment and general society. But increasingly they are being internalised to business.

So presumably, if the Aral Sea and Lake Chad are taken as examples, the benefits associated with the diversion of the rivers for irrigation should have been balanced out against (or at least taken into consideration) with the environmental and social costs of the lakes drying up. As much could be said of Australia over allocating water from the Murray-Darling basins. The tendency is to do that which provides returns within a commercial investment period (3 to 10 years?) especially at a state level, and ignores the larger collective issues and what might happen when a big rare event occurs, for example, a 10 year drought.

The question of what decision making process should be applied in such circumstances is often raised. R2A, as due diligence engineers have always used the Australian High Court’s case law for safety matters. The question of whether or not this could be applied to Sustainability Risk Management is an interesting possibility and the subject of the address. Whilst lawyers always insert caveats regarding the interpretation of legislation, there seems to be a general agreement that negligence cases can be instructive on what might constitute "reasonably practicable" steps to prevent harm.

The indications to date are encouraging. It has most certainly been applied in the question of the management of electrical assets for bushfires. The Powerline Bushfire Safety Taskforce’s report into the Black Saturday fires used this approach per advice from R2A. An example of an expert opinion by Richard Robinson in New Zealand using common law due diligence as a defence against negligence in an environmental legislative context is available at New Zealand EPA. This appears to have been well received by relevant legal counsel at the time although the opinion notes that it was not endeavouring to create a new test under the Resource Management Act 1991.

The essential aspect of due diligence as a defence against negligence is that foreseeable harm to neighbours should be appropriately managed. If the concept of neighbours is extended to include all future neighbours then the possibility a sustainability due diligence argument arises. That is, provided a proposed project or plan is not prohibitively harmful to both present and all future neighbours, and all reasonable practicable precautions have been provided to protect all these neighbours for all reasonably foreseeable issues, then the project ought to proceed. This would be a positive demonstration of sustainability due diligence.

EEA R2A Due Diligence Workshop Wrap Up

As a new addition to the R2A Consulting team, the timing of the recent EEA (Engineering Education Australia) and R2A ‘Engineering Due Diligence’ workshop was such that I was able to attend in my first few weeks of my new role.

Richard Robinson presented the workshop with eight participants from various industries and locations in Australia, which provided for interesting and varied discussion.

As a new addition to the R2A Consulting team, the timing of the recent EEA (Engineering Education Australia) and R2A ‘Engineering Due Diligence’ workshop was such that I was able to attend in my first few weeks of my new role.

Richard Robinson presented the workshop with eight participants from various industries and locations in Australia, which provided for interesting and varied discussion.

The workshop was the first of its kind following the recent partnership between R2A and EEA. Previous workshops had been more structured and closely followed the framework of the R2A text (2013) Risk and Reliability: Engineering Due Diligence, whereas the focus of this workshop explored in greater depth the queries and views of the participants in attendance.

The topics that stimulated most discussion amongst the group were -

- Risk paradigms as they relate to business, projects and safety

- Implications of the model Work Health and Safety Act

- Limitations of the risk management standard as a tool to manage critical vulnerabilities

- Determining critical success factors and undertaking a vulnerability assessment

- Establishing time sequence diagrams

- Establishing threat-barrier diagrams and locating the legal loss of control point

Of interest also was the diverse range of legal and technical examples that Richard drew upon to support the points of discussion that demonstrate due diligence or not, the case may have been.

The workshop format worked well and the feedback from the group was overwhelmingly positive. And no R2A workshop would be complete without the entertainment of a good set of well delivered jokes!

R2A is set to conduct more due diligence workshops like this in 2014 which I think will be of great value to personnel of varied responsibility including but certainly not limited to company directors, senior executives and project managers.

Risk Appetite

Boards are responsible for the good governance of the organisation and risk management is an essential aspect of this.Diligently balancing competing priorities with limited resources requires an organisational expression of risks and rewards in the value system of the board. In the business community this has often been expressed as risk appetite meaning that an outstanding outcome can justify taking greater chances to achieve success. In policy terms it means encouraging the organisation to select projects and programs with greater rewards for similar effort, and is to be applauded. This is a positive demonstration of business due diligence.However, safety has a different perspective. Here often, the consequences of failure are so high that there is simply no appetite for it. Instead, provided the situation is not prohibitively dangerous, the requirement is for (safety) risk to be eliminated or reduced so far as is reasonably practicable, a matter which can be forensically tested in court1.This is a positive demonstration of safety due diligence. Recognised good practice in the form of guidelines and standards is a starting point.In statistical terms, due diligence is primarily about dealing with outliers and black swans (especially to third parties) that create potential showstoppers, rather than optimising the middle ground, which appears to be the position most risk management programs try to achieve. In our experience, most risk management programs involving risk appetite concepts are about optimising the most likely commercial corporate position rather than preventing catastrophes.For technological business which mainly deal with downside risk, the term risk appetite seems inappropriate at least for safety aspects. A better term may be a risk tolerance statement or, keeping it generic across business and safety, a risk position statement.A risk position statement is an articulation of the Board’s understanding of the key risk issues for the business and their understanding of the management and optimisation of these risks. It is almost a quality assurance document to ensure the Board can transparently demonstrate risk management governance to stakeholders including the community and government.From a Board viewpoint, the safety risk position will not be driven by risk (consequence and likelihood) but rather criticality (consequences) and what can actually be done to eliminate or minimise the risk. For example, risk tolerances will vary depending on the precautionary options available for a particular issue and the resources available at the time to address the issue.1 For example from Worksafe Australia interpreting the model WHS act (as viewed at): http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/SWA/about/Publications/Documents/607/Interpretive%20guideline%20-%20reasonably%20practicable.pdf 15 July 2013: What is ‘reasonably practicable’ is an objective testWhat is ‘reasonably practicable’ is determined objectively. This means that a duty-holder must meet the standard of behaviour expected of a reasonable person in the duty-holder’s position and who is required to comply with the same duty.There are two elements to what is ‘reasonably practicable’. A duty-holder must first consider what can be done - that is, what is possible in the circumstances for ensuring health and safety. They must then consider whether it is reasonable, in the circumstances to do all that is possible.This means that what can be done should be done unless it is reasonable in the circumstances for the duty-holder to do something less.This approach is consistent with the objects of the WHS Act which include the aim of ensuring that workers and others are provided with the highest level of protection that is reasonably practicable.

Critical Limitations of Monte Carlo Simulations

Monte Carlo simulations have become de rigueur for project risk assessments. There is no doubt the use of monte carlo simulations will provide sound insight into the most likely project outcomes.

However from a due diligence perspective there are major limitations when it comes to the long tail (low probability) distribution (high consequence) outcomes. Consider the situation where three long tail (say 1 in 1000) issues need to converge to cause total project failure. Collectively, that’s a 1 in a billion chance. To test for that, at least 1,000,000,000 trials would need to be completed. To make that statistically significant there would need to be at 10 to 100 billion trials.

Monte Carlo simulations have become de rigueur for project risk assessments. There is no doubt the use of monte carlo simulations will provide sound insight into the most likely project outcomes.

However from a due diligence perspective there are major limitations when it comes to the long tail (low probability) distribution (high consequence) outcomes. Consider the situation where three long tail (say 1 in 1000) issues need to converge to cause total project failure. Collectively, that’s a 1 in a billion chance. To test for that, at least 1,000,000,000 trials would need to be completed. To make that statistically significant there would need to be at 10 to 100 billion trials.

No one does that. Further, that assumes that the long tail issues have been accurately described. Usually what happens is that the long tails are just ignored as being hard to know and statistically insignificant anyway. This means credible (although rare) critical possibilities are just ignored.

The R2A Project Due Diligence process addresses this shortfall.