SFAIRP Culture

The Work Health & Safety (WHS) legislation has changed the way organisations are required to manage safety issues. With the commencement of the legislation in WA on 31 March 2022, as well as the introduction of criminal manslaughter provisions in some states, there appears to be an increased energy around safety due diligence.

The legislation requires SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable).

A duty imposed on a person to ensure health and safety requires the person:

(a) to eliminate risks to health and safety, so far as is reasonably practicable; and

(b) if it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate risks to health and safety, to minimise those risks so far as is reasonably practicable.

This means that the historical concepts of ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable), risk tolerability and risk acceptance do not apply.

From the handbook for the Risk Management Standard (ISO 31000):

Importantly, contemporary WHS legislation does not prescribe an ‘acceptable’ or ‘tolerable’ level of risk—the emphasis is on the effectiveness of controls, not estimated risk levels. It may be useful to estimate a risk level for purposes such as communicating which risks are the most significant or prioritising risks within a risk treatment plan. In any case, care should be taken to avoid targeting risk levels that may prevent further risk minimisation efforts that are reasonably practicable to implement.

(SA/SNZ HB 205:2017 page 14)

In cultural terms, James Reasons outlines three types of risk culture: pathological, bureaucratic and generative.

The SFAIRP approach is attempting to move safety from the pathological question: Is this bad enough that we have to do something about it, to the generative perspective: Here’s a good idea, why wouldn’t we do it?

In this framework, Codes of Practice and Standards are the bureaucratic starting point. The objective is to do better than that, when reasonably practicable to do so. The aim is the highest reasonable level of protection.

The Act ensures a ‘transparent bias’ in favour of safety. As the model act says (and all jurisdictions including NZ have adopted):

… regard must be had to the principle that workers and other persons should be given the highest level of protection against harm to their health, safety and welfare from hazards and risks arising from work as is reasonably practicable.

This is a change in mindset for many organisations, but one which easily aligns with human nature.

On a personal level, we (at R2A) are always trying to do the best we can especially for others. This is one of the reasons I continue to work on Apto PPE, a line of fit-for-purpose female hi vis workwear including a maternity range.

I know that females only represent a small proportion of the engineering and construction section (around 10%), but the question shouldn’t be “is the current options of PPE for women bad enough that we need to do something about it?”

The question should be: Can we do better than scaled down men’s PPE? And Apto PPE is happy to provide an option for organisations that want to do better.

SFAIRP not equivalent to ALARP

The idea that SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable) is not equivalent to ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) was discussed in Richard Robinson’s article in the January 2014 edition of Engineers Australia Magazine generates commentary to the effect that major organisations like Standards Australia, NOPSEMA and the UK Health & Safety Executive say that it is. The following review considers each briefly. This is an extract from the 2014 update of the R2A Text (Section 15.3).

The idea that SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable) is not equivalent to ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) was originally discussed in Richard Robinson’s article in the January 2014 edition of Engineers Australia Magazine. At the time, it generated much commentary to the effect that major organisations like Standards Australia, NOPSEMA and the UK Health & Safety Executive say that it is.

Fast forward to 2022 and this is still the case.

The following review considers each briefly. This is an extract from the 2022 update of the R2A Text Engineering Due Diligence – How To Demonstrate SFAIRP (Section 19.3).

The UK HSE’s document, ALARP “at a glance”1 notes:

“You may come across it as SFAIRP (“so far as is reasonably practicable”) or ALARP (“as low as reasonably practicable”). SFAIRP is the term most often used in the Health and Safety at Work etc Act and in Regulations. ALARP is the term used by risk specialists, and duty-holders are more likely to know it. We use ALARP in this guidance. In HSE’s view, the two terms are interchangeable except if you are drafting formal legal documents when you must use the correct legal phrase.”

R2A’s view is that the prudent approach is to always use the correct legal term in the way the courts apply it, irrespective of what a regulator says to the contrary.

NOPSEMA are quite clearly focussed on the precautionary approach to risk. Their briefing paper on ALARP2 indicates in the Core Concepts that:

“Many of the requirements are qualified by the phrase “reduce the risks to a level that is as low as reasonably practicable”. This means that the operator has to show, through reasoned and supported arguments, that there are no other practical measures that could reasonably be taken to reduce risks further.” (Bolding by R2A).

That is, NOPSEMA wish to ensure that all reasonable practicable precautions are in place which is the SFAIRP concept. Indeed, later in Section 8, Good practice and reasonable practicability, there is a discussion concerning the legal, court driven approach to risk. Whilst ALARP is mostly used elsewhere in the document, here NOPSEMA notes:

“When reviewing health or safety control measures for an existing facility, plant, installation or for a particular situation (such as when considering retrofitting, safety reviews or upgrades), operators should compare existing measures against current good practice. The good practice measures should be adopted so far as is reasonably practicable. It might not be reasonably practicable to apply retrospectively to existing plant, for example, all the good practice expected for new plant. However, there may still be ways to reduce the risk e.g. by partial solutions, alternative measures, etc.” (Bolding by R2A).

Standards Australia seems to be severely conflicted in this area in many standards, some of which are called up by statute. For example, the Power System Earthing Guide presents huge difficulties.

Another example is AS 5577 – 2013 Electricity network safety management systems. Section 1.2 Fundamental Principles point (e): which requires life cycle SFAIRP for risk elimination and ALARP for risk management:

Hazards associated with the design, construction, commissioning, operation, maintenance and decommissioning of electrical networks are identified, recorded, assessed and managed by eliminating safety risks so far as is reasonably practicable, and if it is not reasonably practicable to do so, by reducing those risks to as low as reasonably practicable. (Bolding by R2A).

It seems that Standards Australia simply do not see that there is a difference. The terms appear to be used interchangeably.

Safe Work Australia is only SFAIRP3. There does not appear to be any confusion whatsoever. For example, the Interpretative Guideline – Model Work Health and Safety Act The Meaning of ‘Reasonably Practicable’ indicates:

“What is ‘reasonably practicable’ is determined objectively. This means that a duty-holder must meet the standard of behaviour expected of a reasonable person in the duty-holder’s position and who is required to comply with the same duty.

“There are two elements to what is ‘reasonably practicable’. A duty-holder must first consider what can be done - that is, what is possible in the circumstances for ensuring health and safety. They must then consider whether it is reasonable, in the circumstances to do all that is possible.

“This means that what can be done should be done unless it is reasonable in the circumstances for the duty-holder to do something less.

“This approach is consistent with the objects of the WHS Act which include the aim of ensuring that workers and others are provided with the highest level of protection that is reasonably practicable.”

ALARP is simply not mentioned, anywhere.

Although the ALARP verses SFAIRP debate continues in many places and the current position of many is that SFAIRP equals ALARP; nothing could be further from the truth.

For engineers, the meaning is in the method; results are only consequences.

SFAIRP represents a fundamental paradigm shift in engineering philosophy and the way engineers are required to conduct their affairs.

It represents a drastically different way of dealing with future uncertainty.

It represents the move from the limited hazard, risk and ALARP analysis approach to the more general designers’ criticality, precaution and SFAIRP approach.

That is;

From: Is the problem bad enough that we need to do something about it?

To: Here’s a good idea to deal with a critical issue, why wouldn’t we do it?

SFAIRP is paramount in Australian WHS legislation and has flowed into Rail and Marine Safety National law, amongst others.

In Victoria, SFAIRP has now also been incorporated into Environmental legislation.

Apart from the fact that SFAIRP is absolutely endemic in Australian legislation with manslaughter provisions to support it proceeding apace, SFAIRP is just a better way to live.

It presents a positive, outcome driven design approach, always testing for anything else that can be done rather than trusting an unrepeatable (and therefore unscientific) estimation of rarity for why you wouldn’t.

If you'd like to learn more about SFAIRP for Engineering Due Diligence, you may be interested in purchasing our textbook. If you'd like to discuss how R2A can help your organisation, fill out our contact form and we'll be in touch.

Editor's note: This article was originally published on 22 January 2014 and has been updated for accuracy and comprehensiveness.

1 https://www.hse.gov.uk/managing/theory/alarpglance.htm viewed 21 February 2022

2 https://www.nopsema.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021-03/A138249.pdf viewed 21 February 2022

3https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/2002/guide_reasonably_practicable.pdf viewed 21 February 2022

ALARP vs SFAIRP revisited

The ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) versus SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable) debate appears to continue in many places, for example, AS/NZS2885.6:2018 Pipeline Safety Management. The current position of many is that SFAIRP equals ALARP and that any view to the contrary is just arguing about the number of angels on a pinhead.Nothing could be further from the truth. For engineers, the meaning is in the method; results are only consequences.

SFAIRP represents a fundamental paradigm shift in engineering philosophy and the way engineers are required to conduct their affairs.

It represents a drastically different way of dealing with future uncertainty. It represents the move from the limited hazard, risk and ALARP analysis approach to the more general designers’ criticality, precaution and SFAIRP approach.

That is, from:Is the problem bad enough that we need to do something about it?To:Here’s a good idea to deal with a critical issue, why wouldn’t we do it?

Paradigm is a much misused word and it is perhaps necessary to clarify what it means. In Thomas Kuhn’s seminal work, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, a paradigm is a universally recognised knowledge system that for a time providea model problems and solutions to a community of practitioners. He provides a notable series of scientific turning points associated with names like Copernicus, Newton, Lavoisier and Einstein. His point is that a new theory or approach is not accepted by the current practitioners since the theory often affects the work of a specialist group on whom the new theory impinges. And in doing so, reflects on much of the work that group has already completed. Its assimilation requires reconstruction of the prior approach and a re-evaluation of prior fact that is seldom completed by a single individual. In fact, it usually requires a generational shift.SFAIRP is paramount in Australian WHS legislation and has flowed into Rail and Marine Safety National law, amongst others. In Victoria, SFAIRP has now been incorporated into Environmental legislation. And, apart from the fact that SFAIRP is absolutely endemic in Australian legislation with manslaughter provisions to support it proceeding apace, SFAIRP is just a better way to live. It presents a positive, outcome driven design approach, always testing for anything else that can be done rather than trusting an unrepeatable (and therefore unscientific) estimation of rarity for why you wouldn’t.

If you’d like to hear Richard & Gaye discuss SFAIRP versus ALARP, check the below podcast episode.

Managing Critical Risk Issues: Synthesising Liability Management with the Risk Management Standard

The importance of organisations managing critical risk issues has been highlighted recently with the opening hearings of the coronial inquest into the 2016 Dreamworld Thunder River Rapids ride tragedy that killed four people.

In a volatile world, boards and management fret that some critical risk issues are neither identified nor managed effectively, creating organisational disharmony and personal liabilities for senior decision makers.

The obligations of WHS – OHS precaution based legislation conflict with the hazard based Risk Management Standard (ISO 31000) that most corporates and governments in Australia mandate. This is creating very serious confusion, particularly with the understanding of economic regulators.

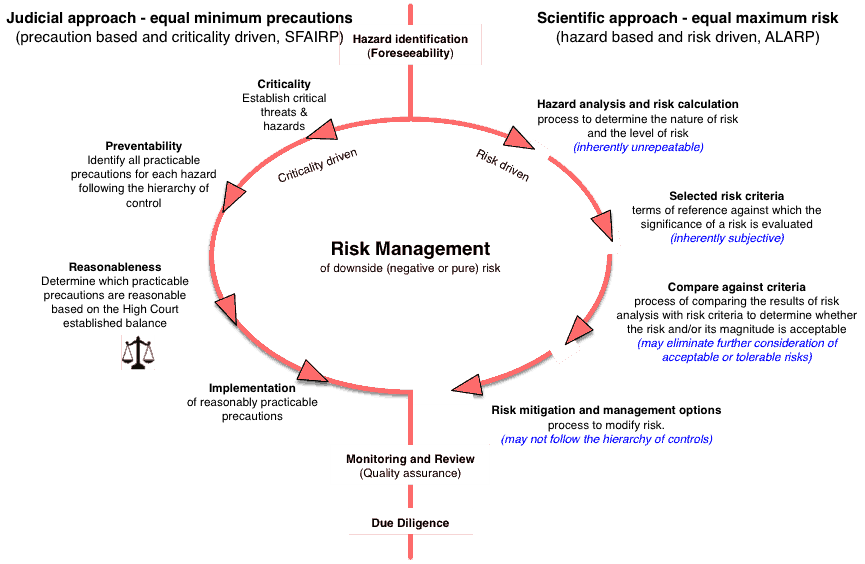

The table below summarises the two approaches.

| Precaution-based Due Diligence (SFAIRP) | ≠ | Hazard-based Risk Management (ALARP) | |

| Precaution focussed by testing all practicableprecautions for reasonableness. | Hazard focussed by comparison to acceptable ortolerable target levels of risk. | ||

| Establish the context

Risk assessment (precaution based): Identify credible, critical issues Identify precautionary options Risk-effort balance evaluation Risk action (treatment) |

Establish the context Risk assessment (hazard based): (Hazard) risk identification (Hazard) risk analysis (Hazard) risk evaluation Risk treatment |

||

| Criticality driven. Normal interpretation ofWHS (OHS) legislation & common law |

Risk (likelihood and consequence) driven Usual interpretation of AS/NZS ISO 31000[1] |

||

A paradigm shift from hazard to precaution based risk assessment

Decision making using the hazard based approach has never satisfied common law judicial scrutiny. The diagram below shows the difference between the two approaches. The left hand side of the loop describes the legal approach which results in risk being eliminated or minimised so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP) such as described in the model WHS legislation.

Its purpose is to demonstrate that all reasonable practicable precautions are in place by firstly identifying all possible practicable precautions and then testing which are reasonableness in the circumstances using relevant case law.

The level of risk resulting from this process might be as low as reasonably practicable (ALARP) but that’s not the test that’s applied by the courts after the event. The courts test for the level of precautions, not the level of risk. The SFAIRP concept embodies this outcome.

The target risk approach, shown on the right hand side, attempts to demonstrate that an acceptable risk level associated with the hazard has been achieved, often described as as low as reasonably practicable or ALARP. But there are major difficulties with each step of this approach as noted in blue.

SFAIRP v ALARP

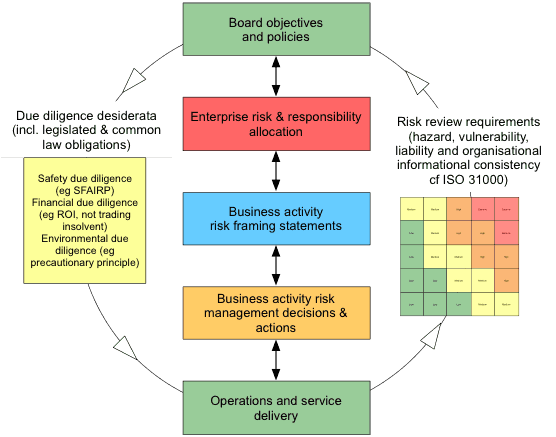

However, there is a way forward that usefully synthesises the two approaches, thereby retaining the existing ISO 31000 reporting structure whilst ensuring a defensible decision making process.

Essentially, high consequence, low likelihood risk decisions are based on due diligence (for example, SFAIRP, ROI, not trading whilst insolvent and the precautionary principle, consistent with the decisions of the High Court of Australia) whilst risk reporting is done via the Risk Management Standard using risk levels, heat maps and the like. This also resolves the tension between the use of the concepts of ‘risk appetite’ (very useful for commercial decisions) and ‘zero harm’ (meaning no appetite for inadvertent deaths).

Essentially the approach threads the work completed (often) in silos by field / project staff into a consolidated framework for boards and executive management.

If you'd like to discuss how we can assist with identifying and managing critical risk issues within your organisation, we'd love to hear from you. Head to our contact page to organise a friendly chat.

[1] From the definition in AS/NZS ISO 31000: 2.24 risk evaluation process of comparing the results of risk analysis (2.21) with risk criteria (2.22) to determine whether the risk (2.1) and/or its magnitude is acceptable or tolerable.

Energy Safety Report Released

The Release of the Final Report and Government Response - Review of Victoria's Electricity and Gas Network Safety Framework has occurred and is available at https://engage.vic.gov.au/electricity-network-safety-review.R2A is quoted a number of times in the report.Two of the key recommendations, supported in principle by the government, are:

34 All energy safety legislation should be consolidated in a single new energy safety Act, replacing the Gas Safety Act 1997, Electricity Safety Act 1998, those elements of the Pipelines Act 2005 that relate to safety, and the Energy Safe Victoria Act 2005.35 The general safety duties within the new consolidated energy safety legislation should be based around a consistent application of the principle that risks should be reduced so far as is “reasonably practicable” aligning with the definition adopted in the Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004.

Recommendation 35 does not sit well with a significant number of Australian Standards which continue to use an ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) approach, supported by a target or tolerable level of risk and safety instead of the ‘so far as is reasonably practicable’ approach of the 2004 Victoria OHS Act and the model WHS legislation adopted in almost all other Australian jurisdictions, and in New Zealand.Such standards particularly include AS2885 (the pipeline standard), AS5577 (electricity network safety), AS (IEC) 61508 (functional safety) and its derivatives.R2A has previously commented on this issue. We (also) regularly have had to overturn the ALARP approach in these standards based on relevant legal advice.I'll be presenting the basis for this need to the Chemeca 2018 conference in Queenstown on 2nd October in a session entitled: Gas Pipelines and the Changing Face of Australian Energy Regulation.

Risk Engineering Body of Knowledge

Engineers Australia with the support of the Risk Engineering Society have embarked on a project to develop a Risk Engineering Book of Knowledge (REBoK). Register to join the community.

The first REBoK session, delivered by Warren Black, considered the domain of risk and risk engineering in the context risk management generally. It described the commonly available processes and the way they were used.

Following the initial presentation, Warren was joined by R2A Partner, Richard Robinson and Peter Flanagan to answer participant questions. Richard was asked to (again) explain the difference between ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) and SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable).

The difference between ALARP and SFAIRP and due diligence is a topic we have written about a number of times over the years. As there continues to be confusion around the topic, we thought it would be useful to link directly to each of our article topics.

Does ALARP equal due diligence, written August 2012

Does ALARP equal due diligence (expanded), written September 2012

Due Diligence and ALARP: Are they the same?, written October 2012

SFAIRP is not equivalent to ALARP, written January 2014

When does SFAIRP equal ALARP, written February 2016

Future REBoK sessions will examine how the risk process may or may not demonstrate due diligence.

Due diligence is a legal concept, not a scientific or engineering one. But it has become the central determinant of how engineering decisions are judged, particularly in hindsight in court.

It is endemic in Australian law including corporations law (eg don’t trade whilst insolvent), safety law (eg WHS obligations) and environmental legislation as well as being a defence against (professional) negligence in the common law.

From a design viewpoint, viable options to be evaluated must satisfy the laws of nature in a way that satisfies the laws of man. As the processes used by the courts to test such options forensically are logical and systematic and readily understood by engineers, it seems curious that they are not more often used, particularly since it is a vital concern of senior decision makers.

Stay tuned for further details about upcoming sessions. And if you are needing clarification around risk, risk engineering and risk management, contact us for a friendly chat.