Review of Victoria's Electricity and Gas Network Safety Framework

On 19 January 2017, the Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change announced an independent review of Victoria’s Electricity Network Safety Framework, to be chaired by Dr Paul Grimes. On 5 May 2017, the Minister announced an expansion to the review's terms of reference to include Victoria’s gas network safety framework.It has been more than a decade since the current safety framework has been in place and it is timely to review the existing arrangements to ensure they adequately reflect the needs of the community in an increasingly complex environment.The review will include extensive consultation with industry and the community to inform the development of a final report and recommendations.Consistent with the expanded terms of reference, the Review of Victoria’s Electricity and Gas Network Safety Framework examines the safety framework applicable to the electricity and gas networks in Victoria and assesses its effectiveness in achieving desired safety outcomes. It will review the design and adequacy of the safety regulatory obligations, incentives and other arrangements governing the safety of Victoria’s electricity and gas networks.The existing Secretariat established within the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning to support the independent reviewer, Dr Paul Grimes, has been additionally resourced.Submissions for the Issues Paper on the review of Victoria’s electricity network safety framework closed on Friday 28 April. Along with the following organisations, R2A welcomed the opportunity to respond to the independent review.

- AER

- AusNet Services

- Attentis Technology

- CitiPower/Powercor - Submission 1

- CitiPower/Powercor - Submission 2

- Energy and Water Ombudsman of Victoria

- Jemena

- Neca

- r2a

- United Energy

- WorkSafe

Our response focuses on the following particular aspects of the review:

- The objectives of the safety framework in Victoria and an assessment of its effectiveness in achieving safety outcomes.

- The design and adequacy of the safety regulatory obligations (including safety cases and the Electricity Safety Management Scheme), incentives and other arrangements governing energy network businesses and any opportunities for improvement.

R2A’s overall perception is that electrical networks in Australia and New Zealand operate in an evolving and interesting regulatory space with overlapping financial, safety and security of supply issues. There is also a plethora of sometimes contradictory standards. Wending a path that simultaneously satisfies all of the competing issues is complex and fraught with methodological superstition. This undoubtedly creates substantial unnecessary expense and waste.From the viewpoint of an effective safety framework, the key issues we believe are causing the greatest angst at the moment are as follows:

- Competition v Cooperation PolicyThe mantra of competition policy is being considered in isolation from the rest of the competing requirements for the safe (and reliable) delivery of electrical energy. This includes both security of supply and safety generally, and especially in Victoria major bushfires started by the electricity network. For example, high reliability requires redundancy whereas commercial efficiency is typically achieved by running without headroom. The current manifestation of economic competition policy does not deal effectively with disaster scenarios (where cooperation is essential) especially for low likelihood, high consequence events, such as black or ash bushfire days which occur about once every 25 years in Victoria.

- Risk Management Standard v Occupational Health and Safety LegislationThe obligations of Victoria’s Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) legislation conflict with the Risk Management Standard (ISO31000) which most corporates and governments mandate. This is creating very serious confusion, particularly with the understanding of economic regulators.The risk management standard tries to manage ‘risk’ to ‘acceptable’ levels, whereas the 2004 Victorian OHS Act (and now model WHS legislation) ensures that everyone is entitled to the same minimum level of protection (but not necessarily the same level of risk).

- Network Standards with Internal ContradictionsStandards with internal contradictions like AS 5577:2013 – Electrical network safety management systems and the EG(0) Power System Earthing Guide create enormous tensions. Specifically, they advocate using target risk criteria such as ALARP, below which risks are deemed ‘tolerable’ and do not require further action, a position in conflict with the health and safety legislation passed by all Australian parliaments and decisions of the High Court of Australia.

These key points are expanded in the body of the submission together with a possible way forward. See the full response here.

Legal vs Engineered Due Diligence

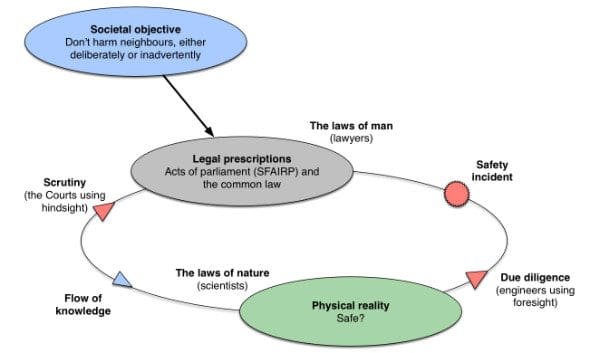

The rise of the model Work Health and Safety legislation, and the need for officers to demonstrate due diligence to ensure that their business has all reasonable practicable safety precautions in place, has been interpreted in different ways.It’s not just a cynical exercise to cover your arse after the event (although that will be one outcome).When conducting investigations into industrial fatalities, the deceased’s co-workers often self-assess to see if there is something that they personally could have done that might have saved their mate. If there was, they feel really, really bad. Conversely, if after due consideration, they conclude that they had done everything in their power to prevent such an occurrence, they feel relieved.This is the natural human response. You can also see this occur with response of parent to the death of a child on ‘P’ plates. The parents always think long and hard about whether they should have done more to train their daughter or son before they were allowed unsupervised on the roads. The Bushfire Royal Commission into the 173 deaths arising from the Black Saturday fire is a similar response, but at a community level.The courts also serve this function, but at a societal level and in a very formal context. When considering cases dealing with health and safety impacts they ask, in effect, “Was there something else that ought to have been done that would have prevented this outcome?”This is our society’s introspection, which helps us feel that justice is served, and that we learn from our mistakes.Accepting this, how do we then demonstrate, before any event, to the satisfaction of our society, that we have done all we ought to, to ensure safety? In general, this will be by demonstrating due diligence in our safety decisions and action, as required by the model Work Health and Safety legislation. But how is due diligence defined?Lawyers, when asked to describe the nature of due diligence, focus on compliance with legislation, regulations and relevant codes of practice, that is, the law. Engineers, when asked if compliance with acts, regulations and codes guarantees that anything is ‘safe’ in reality, reply “no, of course not. Don’t be silly”.This means there is a substantial practicable gap between ‘legal’ and ‘engineered’ due diligence. The reason is that it is not possible for the laws of man (in the form of regulations and compliance) to predict the future. Our legal system (the courts, Royal Commissions and the like) is hindsight driven, applying the underlying principles of moral philosophy like, "do unto others as you would have done to you.”Due diligence engineering takes these moral principles as outlined by laws and court decisions taken in hindsight, and projects them to future human endeavour. This means that engineering due diligence is about the right thing to do, and not just covering your backside.

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Everyone is Entitled to Protection – But not Always the Same Level of Risk

When it comes to dealing with a known safety hazard, everyone is entitled to the same minimum level of protection.

This is the equity argument. It arises from Australia’s work health and safety legislation. It seems elementary. It is elementary. It has also, with the best intentions, been pushed aside by engineers for many years.

The 1974 UK Health and Safety at Work Act introduced the concept of “so far as is reasonably practicable” (SFAIRP) as a qualifier for duties set out in the Act. These duties required employers (and others) to ensure the health, safety and welfare of persons at work.

The SFAIRP principle, as it is now known, drew on the common law test of ‘reasonableness’ used in determining claims of negligence with regard to safety. This test was (and continues to be) developed over a long period of time through case law. In essence, it asks what a reasonable person would have done to address the situation in question.

One key finding elucidating the test is the UK’s Donoghue v. Stevenson (1932), also known as ‘the snail in the bottle’ case, which looked at what ‘proximity’ meant when considering who could be adversely affected by one’s actions.

Another is the UK’s Edwards v. National Coal Board (1949), in which the factors in determining what is ‘reasonably practicable’ were found to include the significance of the risk, and the time, difficulty and expense of potential precautions to address it.

These and other findings form a living, evolving understanding of what should be considered when determining the actions a reasonable person would take with regard to safety. They underpin the implementation of the SFAIRP principle in legislation.

And although in 1986 Australia and the UK formally severed all ties between their respective legislature and judiciary, both the High Court of Australia and Australia’s state and federal parliaments have retained and evolved the concepts of ‘reasonably practicable’ and SFAIRP in our unique context.

In determining what is ‘reasonable’ the Courts have the benefit of hindsight. The facts are present (though their meaning may be argued). Legislation, on the other hand, looks forward. It sets out what must be done, which if it is not done, will be considered an offence.

Legislating (i.e. laying down rules for the future) with regard to safety is difficult in this respect. The ways in which people can be damaged are essentially infinite. That people should try not to damage each other is universally accepted, but how could a universal moral principle against an infinite set of potential events be addressed in legislation?

Obviously not through prescription of specific safety measures (although this has been attempted in severely constrained contexts, for instance, specific tasks in particular industries). And given the complex and coincident factors involved in many safety incidents, how could responsibility for preventing this damage be assigned?

The most appropriate way to address this in legislation has been found, in different places and at different times, to be to invoke the test of reasonableness. That is, to qualify legislated duties for people to not damage each other with “so far as is reasonably practicable.”

This use of the SFAIRP principle in health and safety legislation, as far as it goes, has been successful. It has provided a clear and objective test, based on a long and evolving history of case law, for the judiciary to determine, after an event, if someone did what they reasonably ought to have done before the event to avoid the subsequent damage suffered by someone else. With the benefit of hindsight the Courts enjoy, this is generally fairly straightforward.

However, determining what is reasonable without this benefit - prior to an event - is more difficult. How should a person determine what is reasonable to address the (essentially infinite) ways in which their actions may damage others? And how could this be demonstrated to a court after an event?

Engineers, as a group, constantly make decisions affecting people’s safety. We do this in design, construction, operation, maintenance, and emergency situations. This significant responsibility is well understood, and safety considerations are paramount in any engineering activity. We want to make sure our engineering activities are safe. We want to make sure nothing goes wrong. And, if it does, we want to be able to explain ourselves. In short, we want to do it right. And if it goes wrong, we want to have an argument as to why we did all that was reasonable.

Some key elements of a defensible argument for reasonableness quickly present themselves. Such an argument should be systematic, not haphazard. It should, as far as possible, be objective. And through these considerations it should demonstrate equity, in that people are not unreasonably exposed to potential damage, or risk.

Engineers, being engineers, looked at these elements and thought: maths.

In 1988 the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) were at the forefront of this thinking. In the report of an extensive public inquiry into the proposed construction of the Sizewell B nuclear power plant the inquiry’s author, Sir Frank Layfield, made the recommendation that the HSE, as the UK’s statutory health and safety body, “should formulate and publish guidance on the tolerable levels of individual and social risk to workers and the public from nuclear power stations.”

This was a new approach to demonstrating equity with regards to exposure to risk. The HSE, in their 1988 study The Tolerability of Risk from Nuclear Power Stations, explored the concept. This review looked at what equity of risk exposure meant, how it might be demonstrated, and, critically, how mathematical and approaches could be used for this. It introduced the premise that everyone in (UK) society was constantly exposed to a ‘background’ level of risk which they were, if not comfortable with, at least willing to tolerate. This background risk was the accumulation of many varied sources, such as driving, work activities, house fires, lightning, and so on.

The HSE put forward the view that, firstly, there is a level of risk exposure individuals and society consider intolerable. Secondly, the HSE posited that there is a level of risk exposure that individuals and society consider broadly acceptable. Between these two limits, the HSE suggested that individuals and society would tolerate risk exposure, but would prefer for it to be lowered.

After identifying probabilities of fatality for a range of potential incidents, the HSE suggested boundaries between these ‘intolerable’, ‘tolerable’ and ‘broadly acceptable’ zones, the upper being risk of fatality of one in 10,000, and the lower being risk of fatality of one in 1,000,000.

The process of considering risk exposure and attempting to bring it within the tolerable or broadly acceptable zones was defined as reducing risk “as low as reasonably practicable,” or ALARP. This could be demonstrated through assessments of risk that showed that the numerical probability and/or consequence (i.e. resultant fatalities) of adverse events were lower than one or both of these limits. If these limits were not met, measures should be put in place until they were. And thus reducing risk ALARP would be demonstrated.

The ALARP approach spread quickly, with many new maths- and physics-based techniques being developed to better understand the probabilistic chains of potential events that could lead to different safety impacts. Over the subsequent 25 years, it expanded outside the safety domain.

Standards were developed using the ALARP approach as a basis, notably Australian Standard 4360, the principles of which were eventually brought into the international risk management standard ISO 31000 in 2009. This advocated the use of risk tolerability criteria for qualitative (i.e. non-mathematical, non-quantitative) risk assessments.

And from there, the ALARP approach spread through corporate governance, and became essentially synonymous with risk assessment as a whole, at least in Australia and the UK. It was held up as the best way to demonstrate that, if a safety risk or other undesired event manifested, decisions made prior to the event were reasonable.

But all was not well.

Consider again the characteristics of a defensible argument. It should be systematic, objective and demonstrate equity, in that people are not unreasonably exposed to risk.

Engineers have, by adopting the ALARP approach, attempted to build these arguments using maths, on the premise that, firstly, there are objective acceptable and intolerable levels of risk, as demonstrated by individual and societal behaviour, and, secondly, risk exposure within specific contexts (e.g. a workplace) could be quantified to these criteria. There are problems with mathematical rigour, which introduce subjectivity when quantifying risk in this manner, but on the whole these are seen as a deficit in technique rather than philosophy, and are generally considered solvable given enough time and computing power.

However, there is another way of constructing a defensible argument following the characteristics above.

Rather than focusing on the level of risk, the precautionary approach emphasises the level of protection against risk. For safety risks it does this by looking firstly at what precautions are in place in similar scenarios. These ‘recognised good practice’ precautions are held to be reasonable due to their implementation in existing comparable situations. Good practice may also be identified through industry standards, guidelines, codes of practice and so on.

The precautionary approach then looks at other precautionary options and considers on one hand the significance of the risk against, on the other, the difficulty, expense and utility of conduct required to implement and maintain each option. This is a type of cost-benefit assessment.

In practice, this means that if two parties with different resources face the same risk, they may be justified in implementing different precautions, but only if they have first implemented recognised good practice.

Critically, however, good practice is the ideas represented by these industry practices, standard, guidelines and so on, rather than the specific practices or the standards themselves. For example, implementing an inspection regime at a hazardous facility is unequivocally considered to be good practice. The frequency and level of detail required for inspection will vary depending on the facility and its particular context, but having no inspection regime at all is unacceptable.

The precautionary approach provides a formal, systematic, and objective safety decision-making alternative to the ALARP approach.

Equity with regard to safety can be judged in a number of ways. The ALARP approach considers equity of risk exposure. A second approach, generally used in legislation, addresses equity through eliminating exposure to specific hazards for particular groups of people, without regard to probability of occurrence. For example, dangerous goods transport is prohibited for most major Australian road tunnels regardless of how unlikely they may be to actually cause harm. In this manner, road tunnel users are provided equity in that none of them should be exposed to dangerous goods hazards in these tunnels.

The precautionary approach provides a third course. It examines equity inherent in the protection provided against particular hazards. It provides the three key characteristics in building a defensible argument for reasonableness.

It can be approached systematically, by first demonstrating identification and consideration of recognised good practice, and the decisions made for further options.

It is clearly objective, especially after an event; either the precautions were there or they were not.

And it considers equity in that for a known safety hazard, recognised good practice precautions are the absolute minimum that must be provided to protect all people exposed to the risk. Moving forward without good practice precautions in place is considered unacceptable, and would not provide equity to those exposed to the risk. While further precautions may be justified in particular situations, this will depend on the specific context, magnitude of the risk and the resources available.

Oddly enough, this is how the Courts view the world.

The Courts have trouble understanding the ALARP approach, especially in a safety context. From their point of view, once an issue is in front of them something has already gone wrong. Their role is then to objectively judge if a defendant’s (e.g. an engineer’s) decisions leading up to the event were reasonable.

Risk, in terms of likelihood and consequence, is no longer relevant; after an event the likelihood is certain, and the consequences have occurred. The Courts’ approach, in a very real sense, involves just two questions:

Was it reasonable to think this event could happen (and if not, why not)?Was there anything else reasonable that ought to have been in place that would have prevented these consequences?The ALARP approach is predicated on the objective assessment of risk prior to an event. However, after an event, the calculated probability of risk is very obviously called into question. This is especially so as the Courts tend to see low-likelihood high-consequence events.

If, using the ALARP approach, a safety risk was determined to have less than a one in 1,000,000 (i.e. ‘broadly acceptable’) likelihood of occurring, and then occurred shortly afterwards, serious doubt would be cast on the accuracy of the likelihood assessment.

But, more importantly, the Courts don’t take the level of risk into account in this way. It is simply not relevant to them. If a risk is assessed as ‘tolerable’ or ‘broadly acceptable’ the answer to the Courts’ first question above is obviously ‘yes’. The Courts’ second question then looks not at the level of risk in isolation, but at whether further reasonable precautions were available before the event.

‘Reasonable’ in an Australian legal safety context follows the 1949 UK Edwards v. National Coal Board definition and was refined by the High Court of Australia in Wyong Shire Council v. Shirt (1980). It requires that, when deciding on what to do about a safety risk, one must consider the options available and their reasonableness, not the level of risk in isolation. This is the requirement of the SFAIRP principle.

This firstly requires an understanding of whether options are reasonable by virtue of being recognised good practice. The reasonableness of further options can then be judged by considering the benefit (i.e. risk reduction) they could provide, as well as the costs required to implement them. Options judged as unreasonable on this basis may be rejected. It is only in this calculus that the level of risk (considered first in the ALARP approach) is considered by the Courts.

The ALARP approach does not meet this requirement. If a risk is determined to be ‘broadly acceptable’ then, by definition, risk equity is achieved, and no further precautions are required. But this may not satisfy the Courts’ requirement for equity of minimum protection from risk through recognised good practice precautions. It may also result in further reasonable options being dismissed.

The precautionary approach, on the other hand, specifically addresses the way in which the Courts determine if reasonable steps were taken, in a systematic, objective and equity-based manner. From a societal point of view, the Courts are our conscience. Making safety decisions consistent with how our Courts examine them would seem to be a responsible approach to engineering.

The ALARP approach was a good idea that didn’t work. With the best intentions, it was developed to its logical conclusions and was subsequently found to not meet society’s requirements as set forward by the Courts.

The precautionary approach’s recent prominence has been driven by the adoption of the SFAIRP principle in the National Model Work Health and Safety Act, now adopted in most Australian jurisdictions, followed by similar changes through the Rail Safety National Law, the upcoming Heavy Vehicle National Law and others. And as the common law principle of reasonableness finds it way into more legislation the need for an appropriate safety decision-making approach becomes paramount. It is an old idea made new, and it works. It provides equity.

Is there any good reason to not implement it?

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Should Vic Parliament Cool the Planet to Protect Melbourne?

One of the more interesting philosophical issues arising from the introduction of the model WHS legislation is the question of whether the precautionary principle incorporated in environmental legislation is congruent with the precautionary approach of the model WHS legislation.The environmental precautionary principle is typically articulated as follows:

"If there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation."

Due diligence is normally recognised as a defence for breach of that legislation.The words in Australian legislation are derived from the 1992 Rio Declaration. This formulation is usually recognised as being ultimately derived from the 1980s German environmental policy. The origin of the principle is generally ascribed to the German notion of Vorsorgeprinzip, literally, the principle of foresight and planning.The WHS legislation also adopts a precautionary approach. It basically requires that all possible practicable precautions for a particular safety issue be identified, and then those that are considered reasonable in the circumstances are to be adopted. In a very real sense, it develops the principle of reciprocity as articulated by Lord Atkin in Donoghue vs Stevenson following the Christian articulation, quote:

"The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer's question 'Who is my neighbour?' receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour."

The dark side of the golden rule, as Immanuel Kant noted, is its lack of universality. In his view, it could be manipulated by whom you consider to be your neighbour. Queen Victoria for example, apparently considered neighbours to mean other royalty. The notion of HRH (his or her royal highness) makes it clear that everyone else is HCL (his or her common lowness). It becomes us and them rather than we.Presently, it’s not altogether clear whom our politicians regard as neighbours. At least for Australian citizens, we are all equal before Australian law, irrespective of race, religion and other such factors. So a fellow Australian citizen is at least a neighbour. Security based electoral populism may erode this although so far our courts have remained resolute in this regard. Victorians probably regard current and future Victorians as neighbours. But what about current and future New South Welshmen?Interestingly, in describing what constitutes a due diligence defence under the WHS act, Barry Sherriff and Michael Tooma favourably quote a case from the Land and Environment Court in NSW, suggesting that due diligence as a defence under WHS law parallels due diligence as a defence under environmental legislation.Does this mean that the two precautionary approaches, despite having quite divergent developmental paths, have converged? Tentatively, the answer seems to be ‘yes’. The common element appears to be the concern with uncertainty stemming from the potential limitations of scientific knowledge to describe comprehensively and predict accurately threats to human safety and the environment.So what does this mean? In committing all these apparently convergent principles in legislation, Australian parliaments have been passing legislation to enshrine the precautionary principle as their raison d'être.Consider global warming, which might be natural or man made or a combination of both. As described in an earlier article, a runaway scenario that melts the Greenland ice cap would raise sea levels by seven metres. This would be tough on Melbourne and see many suburbs underwater. We Victorians seem to have the capability to cool the planet to prevent such an outcome. At $10 billion to $20 billion, we can probably afford it judging by a $5 billion desalination plant from which we are yet to take water.If the Victorian Parliament is serious about implementing the legislation it has enacted, then should the Parliament move to cool the planet to protect Melbourne?

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Mixed Messages from Governments on Poles and Wires

According to the Australian Energy Regulator (AER), unexpected events that lead to substantial overspend by owners of poles and wires is capped to 30 per cent.

The rest can be transferred through to the consumer. That is, it does not have to be budgeted for.

Quoting the AER:

"Where an unexpected event leads to an overspend of the capex amount approved in this determination as part of total revenue, a service provider will be only required to bear 30% of this cost if the expenditure is found to be prudent and efficient. For these reasons, in the event that the approved total revenue underestimates the total capex required, we do not consider that this should lead to undue safety or reliability issues."

This has the immediate effect of making poles and wires a valuable saleable asset as the full cost of risk associated with large, rare events like the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria does not need to be included in the valuation. For example, the recent, cumulative $1 billion payout in Victoria has relatively little effect on the profit outcomes for the owner. It also means that the commercial incentive to test for further reasonably practicable precautions to address such events is greatly reduced.

This is inconsistent with accepted probity and governance principles. Ordinarily, all persons (natural or otherwise) are required to be responsible and accountable for their own negligence. At least this is the policy position adopted by responsible organisations like Engineers Australia. Their position requires members to practice within their area of competence and have appropriate professional indemnity insurances to protect their clients. The point is that owners and operators should be accountable for negligence, which the commercial imperative desires to abrogate.

In the case of the Black Saturday bush fires for example, this governance failure has been practically addressed by our customary backstop, the legal system, in the form of the common law claims made by affected parties, and the outcomes of the Bushfire Royal Commission and the flow on work by the Powerline Bushfire Safety Taskforce and the continuing Powerline Bushfire Safety Program.

Particularly, the use of Rapid Earth Fault Current Limiting (REFCL) devices (aka Petersen coils or Ground Fault Neutralisers) on 22-kilovolt lines has been demonstrated to have very significant ability to prevent bushfire starts from single phase grounding faults, faults which the Royal Commission found to be responsible for a significant number of the devastating black Saturday fires. A program to install these in rural Victoria at a preliminary cost of around $500 million appears inevitable, but under the current regulatory regime this cost will be (mostly) passed to the consumer. It is a sad reflection that it takes the death of 173 people to get the worth of such precautions tested and established as being reasonable.

Our Parliaments have seemingly addressed this in a convoluted manner by implementing the model Work Health and Safety laws in all jurisdictions (presently excepting Victoria and Western Australia). This makes officers (directors et al) personally liable for systemic organisational safety recklessness (cases where the officers knew or made or let hazardous occurrences happen) providing for up to five years jail and $600,000 in personal fines. In Queensland, it’s also a criminal matter. There have not been any test cases to date so the effectiveness of this legislation has not been evaluated.

From an engineering perspective, the exclusion of the cost implications of big rare events from the valuation of assets means irrational decisions with regards to the safe operation will inevitably occur and that the community will periodically suffer as a result.

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Safety legislation - Engineering safety - Safety Engineering - Work Health and Safety Act 2012

Questions & Answers

Reader response regarding Richard's article - 'Engineering Implications of the Harmonised Safety Legislation'

This is a response that Richard received following the publication of an article in Engineering Media. Read the article here.

Hi Richard

Safety assurance is one of the 3 key elements of technical integrity (the other elements being fitness-for-service and environmental compliance), and as such risk assessments are a fundamental and important part of our engineering activities.

Your recent article in the January 2012 edition of the Engineers Australia magazine was a very interesting read, and has generated numerous discussions amongst my engineering colleagues. Thus, I am seeking some clarification on a number of statements made in your article, as follows:

Reader question –

Your article suggests that the 5 x 5 risk assessments matrix approach developed under the AS/NZS 4360 or AS/NZS ISO 31000 are fundamentally flawed under the due diligence requirements of the new harmonised safety legislation.

I have a difficulty in accepting this argument in the way that we currently conduct our risk assessments utilising the ISO 31000 standard and a tailored 5 x 5 risk matrix, as follows:

- Hazards/risks are identified.

- Qualitative (and sometimes quantitative) criteria for likelihood and consequences (for safety, performance and environment) are defined against which a risk level (untreated) is determined from a 5 x 5 matrix (i.e. low, medium, high, extreme). Qualified Objective Quality Evidence (OQE), rather than subjective opinion normally supports this assessment.

- Subsequently, a risk mitigation activity is conducted in order to determine credible and precautionary risk mitigation strategies. The mitigation strategies are normally based on a Hierarchy of Controls (safety) approach to ensure that the level of effort (e.g. cost, schedule, resources, redesign, etc) is balanced and commensurate with the level of identified risk.

- Thus, risk mitigation (or treatment) strategies are developed and proposed for implementation, and a subsequent residual (i.e. treated) level of risk is determined. Mitigations can include, for example; redesign, restrictions, additional training, warning/cautions in technical documentation/manuals, etc. In addition, these risk assessments are actively managed and reviewed.

- The residual risk is then presented to the 'customer' (or executive authorities) for consideration for acceptance. Noting that the risk assessments we conduct are technical risk assessments, which are conducted by competent technical staff in consultation with relevant stakeholders (e.g. equipment users/operators, maintainers, trainers, etc).

- Acceptance of the technical risks are then considered for acceptance by the relevant authority while balancing all other risks (e.g. operational, schedule, budget, etc).

Not sure I understand your arguments in the reference EA article, thus, seek your clarification as to how the above process which uses the 5 x 5 risk matrix based on AS/NZS ISO 31000 is considered flawed? Please clarify.

Richard response –

Originally the 5 x 5 matrix approach was derived from US and UK military standards in the 70s. At that time it appears to have been used as a reporting tool for military personnel to explain by exception the issues of concern in the value system of their decision makers. More recently, and especially by accounting and management firms, it has been used as a corporate risk decision criteria tool, especially in the sense that once the dot made it to the green area, no further risk reduction was required. This never satisfied the common law.

You sound like you are using it more in the original military sense. As a reporting tool, its use has always been fine.

Reader question –

By risk criteria, do you mean 'the acceptance of risk criteria'?

Richard response –

Yes. The notion of tolerable or target levels of risk.

Reader question –

Does acceptable risk criteria under the new laws actually mean 'so far as is reasonably practicable (SFARP)'?

If we can achieve SFARP, regardless of whether the residual risk is medium, high, etc, (i.e. provided the level of effort required to reduce the risk to SFARP is balanced and commensurate with the significance of the risk) then is due diligence not demonstrated?

Richard response –

SFARP may mean this. I'm not a lawyer. I avoid the term (and ALARP for that matter), as the final test will be in court, post event, judged to the common law duty of care. So I use the High Court's understanding of that duty and how this court expects it to be demonstrated.

Reader question –

Do you believe that the SFARP principle of common sense precautionary approach on risk reduction replaces the doctrine of risk tolerability (such as ALARP principle) or complements the efforts already accomplished in managing the risk of 'actual harm'?

Richard response –

Yes. The common law precautionary approach replaces the doctrine of tolerable or acceptable risk.

FYI - I have briefed the senior counsel for Defence in this whole matter (the OHS partner in Blake Dawson in Sydney) and he volunteered that the approach I mentioned in that article would demonstrate due diligence under the model act.