Engineering’s Golden Rule

The Golden Rule, or the rule of reciprocity, states that one should treat others as one would wish to be treated. It is an astonishingly widespread maxim, appearing in some form in virtually every major religion and belief system.As a result, the Golden Rule permeates Australian society, in our courts and parliaments, and our laws and judgments. It is an integral and inalienable part of our social infrastructure.Cambridge professor David Howarth’s recent book, Law as Engineering: Thinking About What Lawyers Do, considers some of the implications of this. Howarth’s thesis is that most UK lawyers do not argue in court. Rather, on behalf of their clients, they design and implement, through contracts, laws, deeds, wills, treaties and so forth, small changes to the prevailing social infrastructure.Australian law practice seems to follow a similar pattern, and this is a good and useful thing; without these ongoing small changes to social infrastructure there would be large scale confusion, massive imposition on the court system, and general, often escalating, grumpiness.Engineering serves a similar function. Engineers, on behalf of their clients, design structures and systems that change the material infrastructure of society.This is also a good and useful thing. And, with the history of and potential for significant safety impacts resulting from these physical changes, engineers have over time developed formal design methods to ensure safe outcomes.These methods consider not only the design at hand, but also the wider physical context into which the design will fit. This includes multi-discipline design processes, integrating civil, electrical, mechanical, chemical (and so on) engineering. It also includes consideration of what already exists, and the interfaces that will arise. Road developments will consider their impact on the wider network, as well as nearby rail lines, bike paths, amenities, businesses, residences, utilities, the environment, and so on.Howarth’s book considers this approach to design in the framework of changing social infrastructure. He argues that lawyers, in changing the social infrastructure, ought to consider how these changes may interact with the wider social context to avoid unintended consequences. As an example, he examines the 2009 global financial crisis in which, he argues, many small changes to the social infrastructure resulted in catastrophic negative global impacts.Following formal design processes could have, if not prevented this situation occurring, perhaps at least provided some insight into the potential for its development. But the question arises: how should negative impacts on social infrastructure be identified? In contrast to engineering changes to material infrastructure, social infrastructure changes tend not to have immediate or obvious environmental or health and safety impacts.One option that presents itself is also apparent in good engineering design. Engineers follow the Golden Rule. It is completely embedded in engineering practice, and is supported and reinforced by legislation and judgements. Engineers design to avoid damaging people in a physical sense. Subsequent considerations include environmental harm, economic harm, and so on.A key aspect of this is consideration of who may be affected by infrastructure changes. Proximity is critical here, as well as any voluntary assumption of risk. That is, potential impacts should be considered for all those who may be negatively affected, and who have not elected to put themselves in that position. This is particularly important when others (such as an engineer’s or lawyer’s client) prosper because of such developments.A recent example involving material infrastructure is the Lacrosse tower fire in Melbourne. In this case, a cigarette on a balcony ignited the building’s cladding, with the fire spreading to cladding on 11 floors in a matter of minutes. The cladding was subsequently found to not meet relevant standards, and to be cheaper than compliant cladding.In this case, it appears a design decision was made to use the substandard cladding, presumably with the lower cost as a factor. Although it is certain that the resulting fire scenario was not anticipated as part of this decision, the question remains as to how the use of substandard materials was justified, given the increased safety risk to residents. One wonders if the developers would have made the same choice if they were building accommodation for themselves.In a social infrastructure context, an analogy may be that of sub-prime mortgages being packaged and securitized in the United States, allowing lenders to process home loans without concern for their likelihood of repayment. In this scenario, more consideration perhaps ought to have been given by the lawyers (and their clients) drafting these contracts as to, firstly, how they would interact with the wider context, and, secondly, whether the financial risks presented to the wider community as a result were appropriate. In many respects the potential profits are irrelevant, as they are not shared by those bearing the majority of the risk.The complexities here are manifest. Commercial confidentiality will certainly play a role. No single rule could serve to guide choices when changing social or material infrastructure, and unforeseen, unintended consequences will always arise. But, when considering the ramifications of a decision, a good start might be: how would I feel if this happened to me?

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

2016 The Year in Review

2016 is almost over, and a new year is fast approaching. R2A has had a great year. Below are some highlights we would like to share with you.

In early 2016 we launched the 2016 update of the R2A text, Engineering Due Diligence, at our annual function. This included Richard’s discussion of one of the first prosecutions of an officer of a company under the newly implemented Work Health and Safety legislation.

Shortly after this R2A took on a new business partner, Tim Procter, who returned to R2A after a number of years working in engineering design and consulting. Tim also joined the Engineers Australia College of Leadership and Management Victorian Committee.

And, not to be outdone, in mid 2016 Gaye welcomed the arrival of her second daughter.

Richard, Gaye and Tim are now looking forward to R2A’s next event. On 7 February 2017 R2A and the Victorian Bar will welcome former British MP Professor David Howarth, Reader in Law at Cambridge University, to Engineers Australia’s Melbourne centre. David will discuss his recent book, Law as Engineering, and his thoughts on some interfaces between lawyers and engineers. This will be a larger event than we have previously held – registrations are available through Engineers Australia’s events website. We’re planning that this be the first in a series of seminars exploring this subject. We’d love to see you there.

Interesting Projects

- Transurban: R2A completed a review of all fire safety systems for Transurban’s Australian tunnel portfolio, with a particular focus on what constitutes recognised good practice for aging assets.

- Public Transport Victoria: R2A conducted project due diligence reviews for a number of PTV business cases involving trams, trains, buses, safety and accessibility projects.

- IPART: R2A provided advice to IPART, the NSW electricity safety regulator, on the development of an audit framework for electricity network safety management systems. This was an extensive project that involved reconciling a number of concurrent pieces of legislation to ensure the framework was acceptable to all stakeholders.

- Legal advisory services: R2A advised our clients and their legal counsel in a number of confidential projects relating to the implications of the new WHS legislation for their operations and management.

- Department of Land, Water and Planning: R2A advised DELWP on the implications of the new WHS legislation when considered against the revised Australian National Committee on Large Dams (ANCOLD) guidelines.

- Port of Melbourne Corporations: R2A are undertaking an asset safety due diligence review for a critical piece of Port infrastructure.

Gaye has also been appointed to the Energy Safe Victoria Powerline Bushfire Safety Committee, which will continue its work in 2017.

Conferences

Richard and Tim presented at a number of conferences and seminars in 2016, and are available for similar opportunities in 2017. Please get in touch if you have an event coming up.

- Conference on Railway Excellent (CORE) 2016. Rail Tunnel Fire Safety System Design in a SFAIRP Context. Co-authored by Tim Procter and Lachlan Henderson of Metro Trains Melbourne.

- Asset Management Council and Risk Engineering Society (Melbourne). Risk and Asset Management.

- Dust Explosions Conference, 2016. Dust Explosions and the (Model) WHS Act.

Media

R2A were featured in a number of publications in 2016. The Sourceable articles in particular (listed here chronologically) show our evolving thinking on the implications of the precautionary approach in engineering decision-making and the wider society. This culminated in our final article for the year, which presents our view of the history and philosophy of the ISO/AS31000 (hazard-based) and WHS/common law (precaution-based) approaches to risk management, and the conflicts that have arisen between them.

- Are Australian Standards Becoming Irrelevant? (Sourceable) (No longer available).

- Precaution v Precaution (Sourceable)

- Unknown Knowns: the Perils of Blind Spots (Sourceable)

- Problems and Solutions: The Power of Perspective (Sourceable)

- Legal vs Engineered Due Diligence (Sourceable)

- Everyone is Entitled to Protection – But not Always the Same Level of Risk (Sourceable)

Tim also had a paper published in the 2016 edition of the peer reviewed Australian Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Engineering: Due diligence in the operation and maintenance of heritage assets.

Education

Throughout 2016 Richard delivered public and in-house courses on Engineering Due Diligence to a wide range of attendees.

Richard also continued to present the Swinburne University post-graduate unit Introduction to Risk & Due Diligence. In 2016 this was made a core unit for all engineering post-graduate degrees. Gaye, Tim and R2A associates presented guest lectures during the semester. With this increased enrolment Tim and Gaye will be joining Richard as regular lecturers in 2017.

The 2-day joint R2A/EEA Engineering Due Diligence workshop was again successful this year and will continue in 2017. This workshop is aimed at aspiring directors and senior managers.

Problems and Solutions: The Power of Perspective

Imagine you have a great idea. Perhaps it’s for a start-up venture. Perhaps it’s a new, better way of doing something at your workplace. Perhaps it’s changing the way your business has always done something. Perhaps it’s a substantial capital works project.Each of these will require a business case to convince stakeholders that your idea is, in fact, great, and ought to be implemented. Key aspects considered and explained should include:

- what the good idea is

- how it fits into the current market or organisation

- the benefits it will bring

- the upfront and ongoing costs that it will entail

- the risks the proposed course of action will carry

- what will be done to address these risks

These points can be separated into the three elements of any good business case: the ‘what’, the cost-benefit analysis, and the risk management strategy. The effort and detail required to prepare a convincing business case will vary depending on the idea, but it is unlikely to gain stakeholder acceptance without these three key elements.The ‘what’ and the cost-benefit analysis are generally well understood. However, business case risk management strategies are often difficult to interpret for readers. When you consider that those reading a business case will likely be those deciding if your (great) idea is accepted, the benefit of a clear and concise risk management strategy becomes obvious.So, what does a clear and concise risk management strategy involve? How can one best be prepared and presented? And how can it be made convincing as part of a business case?

Perspectives

The essence of a convincing risk management strategy is emphatically not a statement of “here are the risks, and here is what we will do about them so we don’t think they will happen.”This is, essentially, a list of problems. When deciding on a new course of action as a start-up, a small business or a large organisation, a list of problems in a business case will not give decision-makers confidence.This is especially the case if, as proposed by AS31000 (the Australian Standard for risk management), the goal of the risk management strategy is to ensure risks are ‘tolerable’, which generally means they are unlikely to occur. This argument to unlikelihood is particularly unconvincing if a decision-maker asks “I accept that this risk is unlikely, but what if it happens?”A clearer and more convincing approach is to present a case that states “here are the critical issues, here is why we don’t believe any have been overlooked, and here is why we believe all reasonable measures are in place to address them.”This approach takes a solution (rather than hazard) based approach. A hazard-based approach typically identifies many specific problems and puts them in a list, before thinking of things to do about them. Its perspective is “here’s what could go wrong with my great idea, and here’s why I don’t think it will.”This approach tends to focus on problems and their complexity, going into detailed, oft-impenetrable risk analysis, making it difficult for senior decision-makers to fully comprehend due to the specialist skill-sets required. Problems are often taken out of context for the organisation, and measures identified for each problem tend to be specific to each problem and as such hard to justify. It creates analysis paralysis.A solution-based approach, by contrast, begins by looking at what measures are in place in similar situations, and what further measures might be needed for this specific context. It is actually an options analysis and provides the case for action. Its perspective is "here’s what we should have in place to be confident going ahead with my great idea.”This shift from problems to solutions is key to presenting a convincing business case. It pushes the focus to the way forward, and takes an overarching, holistic viewpoint, making recommendations clearly explicable to senior decision-makers. It ensures the organisation’s context is always considered, and identifies a smaller number of solutions that address multiple potential issues, with a focus on implementing recognised good practice rather than presenting unnecessarily detailed analysis.Where needed, this approach can still generate the level of detail required for budget contingency estimation (e.g. through Monte Carlo simulation). However, it ensures that this detail remains contextually sound, and is only provided where beneficial to decision-making.This approach is also simpler, faster, more efficient, often cheaper, and certainly more defensible if something does go wrong. They provide an argument as to why decisions are diligent, rather than why they are ‘right.’ In short, a solution-based approach provides a far superior decision basis than a hazard-based approach. And that’s something that any business case should aim for.

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Precaution v Precaution

One of the more interesting philosophical issues to emerge in the early 21st century is the relationship, as determined by our courts, between the precautionary principle as implemented in environmental legislation, and the precautionary approach as articulated in the harmonised Work Health and Safety (WHS) legislation.It is interesting because the intellectual source of these ideas appears entirely different, yet the judicial operationalisation of both approaches appears to align.The environmental precautionary principle is generally recognised as coming from Germany’s democratic socialist movement in the 1930s and gained acceptance through the German Green movement in the '70s and '80s as a formal articulation of the German principle of vorsorge-prinzip, that is, quite literally, precaution-principle. In Australia, Parliaments adopted the formulation derived from the Rio convention in the '80s as expressed by the Intergovernmental Agreement on the Environment (1992) between the Commonwealth and the States. That is:"Where there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation.In the application of the precautionary principle, public and private decisions should be guided by:(i) careful evaluation to avoid, wherever practicable, serious or irreversible damage to the environment; and(ii) an assessment of the risk-weighted consequences of various options."The precautionary approach in the model WHS legislation appears to be derived as a defence against negligence in the common law. The common law (commencing in the 12th century with King Henry II) is now established from case law as modified progressively by the judiciary over the next 800 years and, in particular with regard to negligence, by the English law lord Lord Atkin in 1932. He favoured the adoption of a manifestation of the ethic of reciprocity or the golden rule of most major philosophies and religions, expressed in the Christian tradition, as: love your neighbour as yourself meaning do unto others as you would have done unto you.In The precautionary principle, the coast and Temwood Holdings, published in the Environmental and Planning Law Journal 2014, Justice Stephen Estcourt summarises the attempts by the judiciary in Australia to operationalise the environmental precautionary principle over the last 20 years and describes the way various decisions depend on earlier decisions and the way in which aspects of possibly unrelated decisions can be ‘borrowed’ (for want of a better term) from other judgments. For example, he observes that Osborn J in Environment East Gippsland vs VicForests (2010) notes the Shirt calculus. Wyong Shire Council v Shirt (1980) considers the liability of the Council for a water skiing accident, which at first glance would not appear to have any obvious connection to an environmental forestry matter. The issue was a question as to on which side of a sign saying ‘deep water,’ the water was actually deep.What the judges appear to be doing is extracting what are perceived relevant principles from other decisions. This has been conceptually noted by others. In their book Understanding the Model Work Health and Safety Act, Barry Sherriff and Michael Tooma quote a decision from the NSW Land and Environment Court to establish what due diligence means in the model Work Health and Safety legislation. Their point is that, whilst due diligence has been defined in the model WHS Act, the definition closely mirrors the current definition of due diligence in case law. That is, existing environmental case law may serve as a guide to this interpretation for WHS legislation.From the perspective of due diligence engineers trying to reverse engineer the decisions of the Courts, all this is actually quite refreshing. Deconstructing the precautionary principle back to established common law protocols to establish due diligence facilitates a robust pre-event alignment of the laws of nature with the laws of man.

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Unknown Knowns: The Perils of Blind Spots

When demonstrating due diligence, it’s not just what you know and who you know, it’s what you don’t know that you know.

Donald Rumsfeld’s infamous 2002 quote provoked much discussion: “…as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know…there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don't know we don't know. It is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.”

Rumsfeld’s comment emphasised the importance of unforeseen (and possibly unforeseeable) risks. However, he did not speak about a potential fourth category, the ‘unknown knowns.’

T. E. Lawrence wrote of the ideal military organisation having “perfect 'intelligence,' so that we could plan in certainty.” In practice, this is essentially impossible. An executive’s difficulty in knowing what is happening throughout their organisation increases exponentially with the organisation’s size. This gives rise to many well-known and resented management frameworks, including risk and quality systems, communication protocols, timesheets, and so on.

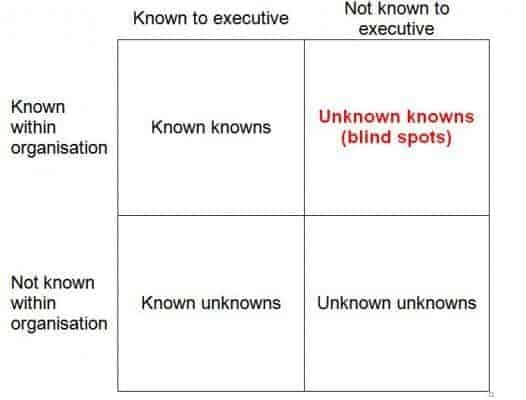

A heuristic technique known as the Johari Window considers the intersection of a person’s state of knowledge with that of their surrounding community. Adapting this to a organisation’s executive’s point of view gives the following Rumsfeldian categories:

These ‘unknown knowns,’ or blind spots, may take a range of forms, including different solutions implemented in different departments for similar problems. At best this is inefficient, and at worst it may demonstrate that, in the case of something going badly wrong, the organisation had a different and clearly reasonable way to address the issue but failed to do so. In this way, recognised good practice may be known and understood within an organisation but not communicated to those who would fund its implementation. A situation may occur in which something goes wrong and good practice measures could have prevented it. This leaves organisations (and relevant managers) open to charges of negligence.

Blind spots may also manifest in the form of operations teams using workarounds to bypass inefficient or perceived low value systems imposed by management. These may arise from benevolent or benign intentions, but can also involve the deliberate flouting of rules or laws, as seen in the recurring ‘rogue financial trader’ scandals.

These scenarios occur again and again in large organisations, and regularly appear in high-profile crisis management media stories. A prominent recent case is Volkswagen’s 2015 diesel emissions controversy. Volkswagen’s CEO admitted that from 2009 to 2014 up to eleven million of its diesel cars (including 91,000 in Australia) had deliberate “defeat” software installed.

This software reduces engine emissions (and hence performance) when it detects the vehicle is undergoing regulatory emissions testing such as that conducted by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). During normal driving, the software increases vehicle performance (and emissions.) This approach was used to have vehicles approved by US EPA regulators while still marketing the cars as high performance vehicles.

Following the admission, Volkswagen suspended sales of some models and stated that it had set aside 6.5 billion euros to deal with the issue and its fallout. The CEO resigned, and a new chair was elected to the supervisory board. Dozens of lawsuits have since been filed against the company, including a US$61 billion suit from the US Department of Justice.

One investigation into this matter noted sociologist Diane Vaughan’s investigation into the 1986 Challenger space shuttle disaster, citing her concept of “normalisation of deviance.” The investigation stated that, rather than explicit or implicit executive direction to game the emissions testing regime, “…it’s more likely that the scandal is the product of an engineering organisation that evolved its technologies in a way that subtly and stealthily, even organically, subverted the rules.”

This can occur through ongoing ‘tweaking’ by system engineers, with no single change considered enough to break ‘the rules’ but with the accumulation over time enough to go past approved limits. Workforce turnover obviously plays a role in this, with the gradually evolving status quo more likely to be accepted than challenged by each new employee. The Volkswagen board chairman’s statement that “we are talking here not about a one-off mistake but a chain of errors” supports this view, with the German investigation’s chief prosecutor subsequently stating that “no former or current board members” were under investigation.

In almost all of these scenarios, it is eventually found that someone, somewhere in the organisation, was aware of the issue and had misgivings about the organisation’s course of action. And when this knowledge becomes public, it often does serious damage to the organisation's reputation.

One approach to tease out these often complex and hidden views, decisions and knowledge is through the ‘generative interview’ technique. This is based on British psychologist James Reason’s classifications of organisational culture. These run on a spectrum from pathological, through bureaucratic, to generative. These classifications signify a range of organisational cultural characteristics. Three key indicators for executive blind spots relate to failure and new ideas; their response to failure, their response to new ideas, and their attitude to issues within the organisation.

Pathological organisations punish failure (motivating employees to conceal it), actively discourage new ideas, and don’t want to know about issues. Bureaucratic organisations provide local fixes for failures, think that new ideas often present problems, and may find out about organisational issues if staff persist in speaking out. Generative organisations implement far-reaching reforms to address failures, welcome new ideas, and actively seek to find issues.

Generative interviews adopt a communication approach with characteristics of a generative organisational culture. They aim to gain the insight of ‘good players’ at a range of levels within an organisation. They are conducted in the spirit of enquiry rather than audit. That is, they are used to look for views, ideas and solutions rather than just for problems or non-conformances, but they listen carefully to issues raised. If an interesting idea or view is common to multiple levels of an organisation, this indicates that it should be further investigated.

When trying to demonstrate diligence in executive decision-making, this harnessing of knowledge at all levels of the organisation is critical. Without it, senior decision-makers may overlook well-known critical issues, and reasonable precautions may be missed. In a post-event investigation, it is difficult to demonstrate diligence if someone within the organisation knew about what could have gone wrong or how to prevent it but could not communicate this to those with the power to address it.

This approach is not a panacea for identifying issues faced by an organisation. However, it helps executives focus on, identify and address their organisational blind spots. In this manner it helps answer a key aspect of due diligence in decision-making: what are our unknown knowns?

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Specialist, Manager or Innovator?

“The analogy with music is useful because nobody can dispute the fact that there are three types of musician: the composer, the performer and the conductor. Nor can anybody disagree that there are world-famous musicians who are outstanding in one of these three professions without having outstanding talent for either of the other two. If we agree on this, we can separate them and deal with them in their special fields.” Desiderius Orban (1978) What is Art all About?Engineers may have more in common with artists than they realise.Young engineers are often stymied by the many career paths available to them. One way to select the best path is to know your strengths. Engineers can excel as specialists (like the first violinist for the MSO), as managers (like the conductor of the MSO) or as a creator or innovator of new goods or services, like a composer. They can also be good at any two and sometimes all three, although this is actually comparatively rare.Orban points out that being good at all three is what is required to be an excellent artist, which is why very good artists are so few in number. But it’s less of an issue for engineers as they usually work in well organised teams with multiple, often overlapping skill sets.Specialists are usually the easiest to identify. Attend a conference or review of published technical papers will suggest who they might be. Organisers show up as managers and consulting engineers, especially after the completion of an MBA. Creators (if they are organised) show up on the rich list. If disorganised, their ideas will be consumed by others and they are likely to be impoverished.All of us have elements of these skills to some extent. The trick is determine your profile and then select a career accordingly. Not only will the engineer do ‘right’ by themselves, they will also achieve the full potential on behalf of the organisations and society they serve.As an example, the diagram above describes a successful consulting practice with two directors with complementary skills profiles.

Timeline of Key Australian Risk Concepts and Events

R2A’s recent work on dam safety led us to develop a timeline of key risk and due diligence concepts and events as they have appeared and influenced Australia. This goes some way to explaining the current divergence between the AS/ISO 31000 hazard-based risk management approach, and the common law and WHS Act precaution-based due diligence approach.In essence, both approaches attempt to demonstrate risk equity, that is, that no one is unreasonably exposed to risk. The key difference between the approaches is that the due diligence approach focuses on ensuring a minimum acceptable level of protection is in place, in the form of precautions. This is an inherently objective test – either the precautions are in place or they are not.In contrast, the hazard-based approach aims to show that a maximum tolerable level of risk is not exceeded, an inherently subjective approach which requires (amongst other things) accurate predictions of the probability of complex potential future events.Both of these approaches have the primary aim: risk equity. However only the precaution-based due diligence approach was developed and has continued to be accepted by the courts and parliaments of Australia, as clearly shown in the timeline below.Blue relates to the precaution-based (SFAIRP) approach, red to the hazard-based (ALARP) approach.1932 Concept of ‘neighbours’ developed for negligence cases in the UK[1].1949 Disproportionality ‘unpacked’ in the Coal Boards case in the UK.[2].1974 ‘So Far As Is Reasonably Practicable’ (SFAIRP) concept introduced in UK safety legislation [3]. This incorporated a demonstration of risk equity in the form of minimum levels of precautions1980 Interpretation of ‘reasonableness’, the common law precautionary balance established by the High Court of Australia (HCA)[4].1982 Issues not ‘remote or fanciful’ must be considered (HCA)[5].1985 Victorian Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Act adopts ‘so far as practicable’[6]1986 Elimination of the remaining ties between the legislature and judiciary of Australia and the UK making the High Court of Australia judicially paramount in Australia[7].1987 UK public inquiry (the Layfield Sizewell B review) recommends the UK Health & Safety Executive (HSE) develop guidance as to the tolerability of safety risk from nuclear power plants.[8]1988 Concept of ‘As Low As Reasonably Practicable’ (ALARP) introduced by UK HSE in response to the Layfield review recommendation. This appears to be an attempt to make safety risk a ‘science’[9] by using target (acceptable or tolerable) levels of risk to demonstrate risk equity.1990 ‘Safety Case’ concept authoritatively articulated in the UK[10].1995 AS4360 risk management standard released, explicitly adopting the ALARP approach[11]. Revised in 1999, retains the ALARP approach[12].2001 That ALARP is equal to SFAIRP formally articulated in UK[13].2004 Maxwell QC reviews failures of acceptable or tolerable risk target approach to safety. Articulates SFAIRP[14]. Equates Victorian OHS Act ‘so far as practicable’ to SFAIRP.2004 AS4360:2004 released, maintaining the ALARP approach[15].2004 Victorian Parliament adopts SFAIRP in legislation[16].2009 AS31000:2009 released, incorporating the ALARP approach from AS4360[17]. This is subsequently referred to in other standards including AS55000:2014 (asset management)[18], and AS5050:2010 (business continuity)[19].2011 Model Work Health and Safety (WHS) legislation adopts SFAIRP approach following the Victorian OH&S Act and due diligence[20] case law.2011 Victorian Government accepts precautionary approach embodied in model WHS legislation by adopting all recommendations of the Powerline Bushfire Safety Taskforce[21].2014 Engineers Australia articulates the difference between SFAIRP and ALARP and issues guidance accordingly[22].Footnotes - [1] UK House of Lords. Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] UKHL 100 1932.[2] UK Court of Appeal CA. Edwards v. National Coal Board.[3] UK Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974.[4] High Court of Australia. Wyong Shire Council vs Shirt (1980) 146 CLR 40.[5] High Court of Australia. Turner v. South Australia (1982) 42 ALR 669.[6] Occupational Health and Safety Act 1985. Parliament of Victoria.[7] Australia Act 1986 (Cth), Australia Act 1986 (UK).[8] F. H. B. Layfield, Great Britain Department of Energy (1987). Sizewell B Public Inquiry Report.[9] The Tolerability of Risk from Nuclear Power Stations. UK Health and Safety Executive.[10] The Public Inquiry into the Piper Alpha Disaster. W D Cullen (1990) London. HMSO.[11] AS4360:1995 – Risk management. SAI Global (1995).[12] AS4360:1999 – Risk management. SAI Global (1999).[13] Reducing Risks, Protecting People. UK Health and Safety Directorate (2001).[14] Occupational Health and Safety Act Review. C Maxwell (2004).[15] AS4360:2004 – Risk management. SAI Global (2004).[16] Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004. Act No. 107/2004[17] AS31000:2009 – Risk management – Principles and guidelines. SAI Global (1999).[18] AS55000:2014 – Asset management - Overview, principles and terminology. SAI Global (2014).[19] AS5050:2010 – Business continuity - Managing disruption-related risk. SAI Global (2010).[20] Model Work Health and Safety Bill. 23 June 2011. Safe Work Australia.[21] Victorian Government Response to The Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission Recommendations 27 and 32. December 2011[22] Engineers Australia, Risk Engineering Society (2014). Safety Case Guideline. Third edition.

Should Vic Parliament Cool the Planet to Protect Melbourne?

One of the more interesting philosophical issues arising from the introduction of the model WHS legislation is the question of whether the precautionary principle incorporated in environmental legislation is congruent with the precautionary approach of the model WHS legislation.The environmental precautionary principle is typically articulated as follows:

"If there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation."

Due diligence is normally recognised as a defence for breach of that legislation.The words in Australian legislation are derived from the 1992 Rio Declaration. This formulation is usually recognised as being ultimately derived from the 1980s German environmental policy. The origin of the principle is generally ascribed to the German notion of Vorsorgeprinzip, literally, the principle of foresight and planning.The WHS legislation also adopts a precautionary approach. It basically requires that all possible practicable precautions for a particular safety issue be identified, and then those that are considered reasonable in the circumstances are to be adopted. In a very real sense, it develops the principle of reciprocity as articulated by Lord Atkin in Donoghue vs Stevenson following the Christian articulation, quote:

"The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer's question 'Who is my neighbour?' receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour."

The dark side of the golden rule, as Immanuel Kant noted, is its lack of universality. In his view, it could be manipulated by whom you consider to be your neighbour. Queen Victoria for example, apparently considered neighbours to mean other royalty. The notion of HRH (his or her royal highness) makes it clear that everyone else is HCL (his or her common lowness). It becomes us and them rather than we.Presently, it’s not altogether clear whom our politicians regard as neighbours. At least for Australian citizens, we are all equal before Australian law, irrespective of race, religion and other such factors. So a fellow Australian citizen is at least a neighbour. Security based electoral populism may erode this although so far our courts have remained resolute in this regard. Victorians probably regard current and future Victorians as neighbours. But what about current and future New South Welshmen?Interestingly, in describing what constitutes a due diligence defence under the WHS act, Barry Sherriff and Michael Tooma favourably quote a case from the Land and Environment Court in NSW, suggesting that due diligence as a defence under WHS law parallels due diligence as a defence under environmental legislation.Does this mean that the two precautionary approaches, despite having quite divergent developmental paths, have converged? Tentatively, the answer seems to be ‘yes’. The common element appears to be the concern with uncertainty stemming from the potential limitations of scientific knowledge to describe comprehensively and predict accurately threats to human safety and the environment.So what does this mean? In committing all these apparently convergent principles in legislation, Australian parliaments have been passing legislation to enshrine the precautionary principle as their raison d'être.Consider global warming, which might be natural or man made or a combination of both. As described in an earlier article, a runaway scenario that melts the Greenland ice cap would raise sea levels by seven metres. This would be tough on Melbourne and see many suburbs underwater. We Victorians seem to have the capability to cool the planet to prevent such an outcome. At $10 billion to $20 billion, we can probably afford it judging by a $5 billion desalination plant from which we are yet to take water.If the Victorian Parliament is serious about implementing the legislation it has enacted, then should the Parliament move to cool the planet to protect Melbourne?

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Are Australian Standards Becoming Irrelevant?

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a standard is “an authoritative or recognised exemplar of correctness, perfection, or some definite degree of any quality.”

Of course, this is but one of several definitions, and there seems to be at least five types of ‘standards.’

- Standards as measures: These are wholly scientific standards. They directly describe standardised measures such as those described in the Système International d'Unités, SI. That is, metre, kilogram, second, ampere, kelvin, mole and candela.

- Specification standards: These describe the physical attributes necessary for harmonised results. For example, bullet and barrel specifications must align to enable a rifle to operate. These use the first meaning extensively and was historically the source of engineering standards organisations.

- Standards as rules: These describe particular technical requirements to achieve standardised performance outcomes, like the Wiring Rules (AS 3000). This can include elements of the first two.

- Design standards: These can be a combination of measures, specifications and rules. It makes them eminently arguable.

For example, Paul Wentworth a partner Minter Ellison in 2011 when discussing AS/NZS 7000 (Overhead Line Design) and the legal status of standards and relevance to professional liability noted that “Engineers should remember that in the eyes of the court, in the absence of any legislative or contractual requirement, an Australian Standard amounts only to an expert opinion about usual or recommended practice. Also, that in the performance of any design, reliance on an Australian Standard does not relieve an engineer from a duty to exercise his or her skill and expertise.”

And in an article in Engineers Australia Magazine of March 2009, Leigh Duthie a partner at Baker & McKenzie noted that “Engineers cannot avoid liability in negligence or for TPA (Trade Practices Act) contravention by simply relying on a current or published standard or code.”

- Technique or method standards: For example, various risk management standards like COSO or AS 31000. These can have elements of the first four ‘standards’ but can also include an aspect requiring the realisation of a particular organisational or community expectation.

The primary difficulty with these standards is that their meaning is in the method. Results are only consequences. That is, the meaning of ‘standard’ ranges from wholly scientific definitions that have no moral attributes to opinions that are promoted to achieve political alignment.

Standards organisations don’t seem to recognise this range of meanings even though it is very important. A technique ‘standard’ is often promoted as having the same reliability as a ‘measure’ standard even though such ‘technique’ standards should really be regarded as opinion pieces.

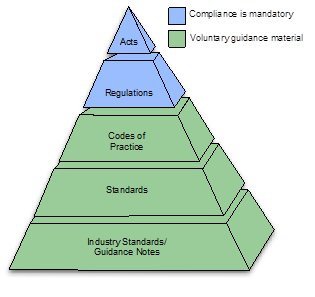

However, these difficulties are being recognised by many. For example, it seems that Australian governments have determined via their legislative processes (especially the model Work Health and Safety Acts, Rail Safety National Law and the like) that Australian Standards will no longer be called up in legislation. Apparently, parliamentary counsel has indicated that it is inappropriate to derogate the power of parliament to unelected standards committees.

The intention is no WHS Act, Regulation or Code of Practice will refer to them. And a Code of Practice under WHS legislation (once approved) has the force of law in many jurisdictions. Established rules standards, like AS 3000 (the Wiring Rules) are applied by making such codes a condition of registration to be an electrician rather than being called up by an electrical safety act or regulation.

Other advice is that for expert witness matters, an engineering guideline developed by a professional body like Engineers Australia, acting within its members’ areas of competence, will always have higher standing to an industry based Australian standard in Australian courts. This means that the rise of Bodies of Knowledge (BoKs) is also becoming more prevalent as a legally superior alternative to standards in practice matters.

There is also an argument that many standards organisations do not comply with professional organisations’ Codes of Ethics with regard to giving credit where credit is due. For example, Australian Standards do not acknowledge the (volunteer) individuals on the relevant committee in a standard, unlike for example, the National Fire Protection Association of the USA. And the floating of the commercial arm of Standards Australia in 2003 (SAI Global Limited) effectively commercialised the volunteer effort and intellectual property contributions of the many contributing Engineers Australia members at least, without recognition.

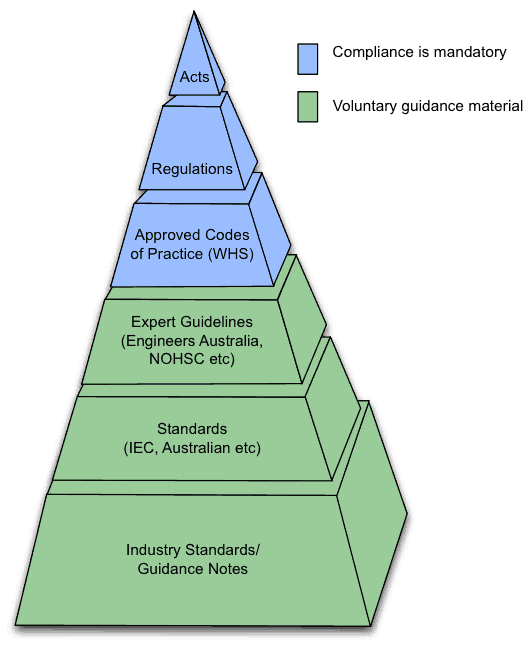

One of the results of all this is that Australian Standards are falling down the hierarchy of significance as shown in the diagram, being displaced by both Codes of Practice and Expert Guidelines. This is certainly making many of them less relevant.

If this becomes an enduring trend, then this has potentially serious implications for commercial organisations like SAI Global which depend on the continuing success of such standards documents.

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Swinburne 2016 Wrap-up

The post-graduate course R2A presents at Swinburne became a core unit in 2016. Over 80 students enrolled in first semester. The course is based around the 2016 edition of the R2A Text.

Presenters from R2A included Gaye Francis, Tim Procter, Richard Robinson and Adriaan den Dulk.

The enrolment numbers were a step up from previous semesters, and the topics students chose for their projects varied accordingly, including transport, construction, waste management, and one particularly memorable demonstration of an exploding mobile phone battery.

We enjoyed the increased diversity in contributions and viewpoints, and we look forward to engaging with more new students in our 2017 Engineering Due Diligence course.

Recommended Reading List

R2A maintains a focus on our directors’ continued personal and professional development. One key area of this is exploring new and historical ideas from the wider engineering context.We often find interesting ideas in our reading, with relevant ideas for engineers, especially as they relate to due diligence and good decision-making.Our recent blogs have discussed titles such as:

A current source of interest is Edwin T. Layton, Jr.’s 1971 award-winning historical classic The Revolt of the Engineers. This seminal text explores the emergence of the non-military engineering profession from the conglomerate of trades and technical workers in mid-19th century USA through to the 1960s.There are many intertwining themes in this text, but perhaps the most influential is the tension that arose (and still exists) between the engineer’s role as a businessperson, and the engineer’s role as an independent expert (similar to a doctor). This conflict was played out through the formation and interplay of the various engineering societies with their differing agendas, and generated an unsuccessful push to place engineers at the centre of public decision-making.This excellent and concise book describes the conditions that led to this episode, and illuminates the need for and role of engineering societies such as The Institute of Engineers Australia. While perhaps not providing definitive answers on how the professional-businessperson tension may be resolved, Layton at least asks the right questions. It is recommended reading for all engineers and engineering students.

Engineers Ethical Standing

A recent edition of the SFPE (Society of Fire protection Engineers of the USA) magazine had an interesting study on professional ethics. Possibly the most arresting image is shown above on the public perception of honesty and ethics.The result is from a Gallup poll where respondents were asked to rate the honesty and ethics of the groups concerned with the table showing the % ranked ‘very high’ or ‘high’. Interestingly, nurses were clear winners with engineers ranked second at around 70%. Lawyers were at about 20% with politicians close to 5%. The article notes that this has been a steady increase since 1976 when the combined percentage for engineers for ‘high’ and ‘very high’ was 48%.

Mixed Messages from Governments on Poles and Wires

According to the Australian Energy Regulator (AER), unexpected events that lead to substantial overspend by owners of poles and wires is capped to 30 per cent.

The rest can be transferred through to the consumer. That is, it does not have to be budgeted for.

Quoting the AER:

"Where an unexpected event leads to an overspend of the capex amount approved in this determination as part of total revenue, a service provider will be only required to bear 30% of this cost if the expenditure is found to be prudent and efficient. For these reasons, in the event that the approved total revenue underestimates the total capex required, we do not consider that this should lead to undue safety or reliability issues."

This has the immediate effect of making poles and wires a valuable saleable asset as the full cost of risk associated with large, rare events like the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria does not need to be included in the valuation. For example, the recent, cumulative $1 billion payout in Victoria has relatively little effect on the profit outcomes for the owner. It also means that the commercial incentive to test for further reasonably practicable precautions to address such events is greatly reduced.

This is inconsistent with accepted probity and governance principles. Ordinarily, all persons (natural or otherwise) are required to be responsible and accountable for their own negligence. At least this is the policy position adopted by responsible organisations like Engineers Australia. Their position requires members to practice within their area of competence and have appropriate professional indemnity insurances to protect their clients. The point is that owners and operators should be accountable for negligence, which the commercial imperative desires to abrogate.

In the case of the Black Saturday bush fires for example, this governance failure has been practically addressed by our customary backstop, the legal system, in the form of the common law claims made by affected parties, and the outcomes of the Bushfire Royal Commission and the flow on work by the Powerline Bushfire Safety Taskforce and the continuing Powerline Bushfire Safety Program.

Particularly, the use of Rapid Earth Fault Current Limiting (REFCL) devices (aka Petersen coils or Ground Fault Neutralisers) on 22-kilovolt lines has been demonstrated to have very significant ability to prevent bushfire starts from single phase grounding faults, faults which the Royal Commission found to be responsible for a significant number of the devastating black Saturday fires. A program to install these in rural Victoria at a preliminary cost of around $500 million appears inevitable, but under the current regulatory regime this cost will be (mostly) passed to the consumer. It is a sad reflection that it takes the death of 173 people to get the worth of such precautions tested and established as being reasonable.

Our Parliaments have seemingly addressed this in a convoluted manner by implementing the model Work Health and Safety laws in all jurisdictions (presently excepting Victoria and Western Australia). This makes officers (directors et al) personally liable for systemic organisational safety recklessness (cases where the officers knew or made or let hazardous occurrences happen) providing for up to five years jail and $600,000 in personal fines. In Queensland, it’s also a criminal matter. There have not been any test cases to date so the effectiveness of this legislation has not been evaluated.

From an engineering perspective, the exclusion of the cost implications of big rare events from the valuation of assets means irrational decisions with regards to the safe operation will inevitably occur and that the community will periodically suffer as a result.

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Implications of the Model WHS Legislation

The consequences of the model WHS (Work Health and Safety) legislation on electrical safety are quite startling, but they have not yet been realised.The legislation requires that risks to health and safety should be eliminated, so far as is reasonably practicable. Section 17 Management of risks of the model act [1] states:A duty imposed on a person to ensure health and safety requires the person:

- to eliminate risks to health and safety, so far as is reasonably practicable; and

- if it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate risks to health and safety, to minimise those risks so far as is reasonably practicable.

That is, if it is reasonably practicable to eliminate a hazard, then it should be done.The bane of electrical regulators is the home handyman working in a roof space and fiddling with the 240-volt conductors. Death is a regular result. The fatalities arising from the home insulation Royal Commission also spring to mind. As reported in the Sydney Morning Herald [2] last year, the management consultant hired to prepare a risk assessment for the Rudd government’s home insulation program says she had no idea that installers could die. She also told the inquiry she wasn’t aware of safety issues surrounding the use of foil, a product linked to three of the deaths.Many of us have been replacing our lights in our houses with energy efficient 12-volt LEDs. Whilst it may be unreasonable to retrospectively replace the 240-volt wiring in the roof space with extra low voltage (ELV) conductors for existing structures, it is obviously quite achievable for new dwellings. If all the wiring in the roof is 12 or 24 volts (and all the 240-volt wiring is in the walls) then the possibility of being electrocuted in a roof space is pretty much eliminated, which is the purpose of the legislation.The penalties for recklessness (knew or made or let it happen) under the model legislation are extraordinary, up to five years jail and $600,000. In some jurisdictions (for example, Queensland) it is also a crime [3].So in the event of a death that would have been prevented with ELV wiring in a dwelling constructed after the commencement of the model WHS act in a particular jurisdiction, the relevant public prosecutor presumably has a duty to prosecute any person, including the officers of a PCBU (person conducting a business or undertaking) that facilitated the fatal 240-volt installation. This would be expected to include officers of firms of builders, consulting engineers, electricians, architects and building surveyors at the very least.

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

[1] See Model Bill 23/6/2011 accessed 21/01/15 at: http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/SWA/about/Publications/Documents/598/Model_Work_Health_and_Safety_Bill_23_June_2011.pdf[2] See: http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-news/we-didnt-expect-death-home-insulation-probe-told-20140407-zqru8.html Accessed 20jan15[3] See Qld Electrical Safety Act 2002. Section 40B. Reckless Conduct – Category 1 (3) A category 1 offence is a crime. The Queensland parliament modified the Qld Electrical Safety act to enable its provisions to be the same as the Qld WHS act.

When is a hazard not a hazard? Or, the issue of failed precautions

… their appearance and their work was as it were a wheel within a wheel. (Ezekiel 1:16)

“It’s turtles all the way down!” (Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time)

R2A consults to a wide range of industries. We advise our clients on topics as diverse as safely emptying a 40-metre-tall sugar silo, procuring a fleet of new Melbourne trams, appropriate decision-making for road tunnel fire emergency response, and corporate governance for electricity industry regulators.

This wonderful diversity of projects lets us take good ideas from one sphere to another, helping our clients implement existing approaches in new contexts to solve known problems. It also shows us recurring problems in risk management approaches. One of the most common is identified hazards not really being hazards.

Formal risk management was introduced to Australia in the 1970s. A pattern then emerged in how organisations often appointed their risk managers. Rather than embarking on a specific ‘risk management’ career path, senior ‘chain-of-command’ managers initially took on risk management responsibilities for their role. As their interest or aptitude developed they increased their risk management portfolio, eventually stepping out of the chain and into the wide-ranging advisory ‘risk manager’ role.

These risk managers have a wide variety of backgrounds, allowing for incredible cross-pollination of their approaches, ideas and techniques as they move between organisations and industries. However, this also leads to an incredible mix of language around risk management concepts. One of the most persistent issues arising from this is the idea that a failed precaution constitutes a hazard.

This issue often appears in the form of concern about following Australian standards. In a design project, for instance, a risk assessment will often identify the risk of not following relevant design standards. But design standards are, without exception, developed to address risks, safety or otherwise. That is, they are a precaution. More precautions must then be added to address this new risk, but each of these introduces a risk if they fail and require still more precautions, and so on ad infinitum – wheels within wheels within wheels, turtles all the way down.

This confusion is promulgated by the Australian risk management standard AS31000 (and its predecessor AS4360), Section 5.5.2 of which notes that “a significant risk can be the failure or ineffectiveness of the risk treatment measures” (i.e. precautions).

Taken in context, this sentence aims to support AS31000’s entirely appropriate focus on monitoring precautions to ensure they remain effective after implementation. In practice however, it further entrenches the idea that failed precautions are, in and of themselves, risks.

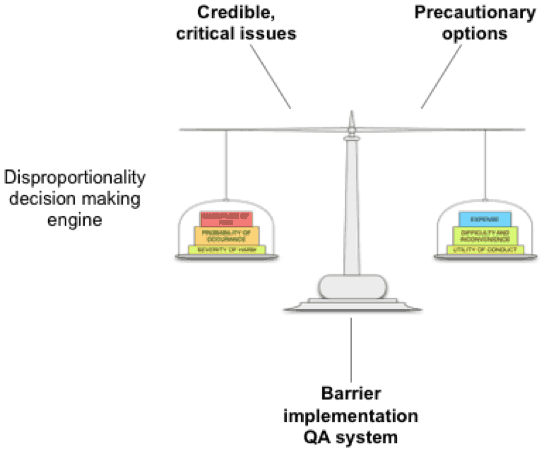

R2A’s ‘Y’ model addresses the problems of this infinite regression by recognising that the monitoring processes which are used to maintain effective precautions form an organisation’s quality assurance/quality control (QA) system.

R2A’s ‘Y’ model

When viewed in this manner, risk management keeps its focus on key precautions for critical issues. The organisation’s QA system (which is generally already established) thus becomes a key element of diligent risk management, rather than a checkbox exercise. This also avoids the need to continuously add lines to a corporate risk register when dealing with a single risk.

We find that this approach not only simplifies the decision-making process as to what precautions are reasonable, it also ensures that risk decisions reported up to senior decision-makers and Boards are clear and concise.

Risk decisions being easier to make and more easily explicable indicates that they will be more easily defended if a risk manifests. We have found our clients to be unanimously in favour of this.

To find out more about R2A’s ‘Y’ model and our wider approach, have a look at the resources on our website, come to one of our EEA Engineering Due Diligence short courses, or purchase the R2A text.

Engineers Australia Safety Case Guidelines Due to Be Released

The Engineers Australia Safety Case Guideline (3rd Edition) is presently being reviewed by Engineers Australia legal counsel.

It is expected to be released by the Risk Engineering Society through Engineers Australia Media in early 2014.

This third edition of the Safety Case Guideline considers how a safety case argument can be used as a tool to positively demonstrate safety due diligence consistent with the model Work Health and Safety (WHS) legislation (Work Safe Australia 2011) and the Rail Safety National law amongst others, and to provide general information concerning the concepts and applications of risk theory to safety case arguments.

The Guideline adopts a precautionary approach to demonstrating safety due diligence, meaning that safety risk should be eliminated or reduced so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP) rather than reducing risk to as low as is reasonably practicable (ALARP) as encouraged by numerous Australian and international standards and regularly used by many Australian engineers. The Guideline emphasises that attempting to equate SFAIRP and ALARP is naively courageous and will not survive post-event judicial scrutiny.

The expected adoption of the Guideline represents the intellectual tipping point in the technical management of safety risk, at least in Australia, since a guideline or code of practice published by practitioners in their area of competence takes legal precedence over an industry-based standard unless that standard is called-up by statute or regulation. The call-up of a standard in legislation is frowned upon by parliamentary counsel since it derogates the power of parliament to unelected standards committees rather defeating the purpose of a parliamentary democracy. Advice is that under the new safety legislation the hierarchy is now:

In a discussion of the legal status of standards, Minter Ellison partner Paul Wentworth concluded that "Engineers should remember that in the eyes of the courts, in the absence of any legislative or contractual requirement, an Australian Standard amounts only to an expert opinion about usual or recommended practice. Also, that in the performance of any design, reliance on an Australian Standard does not relieve an engineer from the duty to exercise his or her own skill and expertise."

Previously, due diligence meant compliance with the laws of man. The Guideline emphasises that to be safe in reality (meaning an absence of harm), one must first manage the laws of nature rather than the laws of man. Safety due diligence therefore requires a positive demonstration of the alignment of the laws of nature with the laws of man, in that order.

This is quite different to demonstrating due diligence in the finance world. Money isn’t real. That is, it does not exist in a state of nature, for example, it does not grow on trees and therefore the laws of nature don’t directly apply to it. This means that in the financial world, due diligence will probably continue to be considered the same as compliance. Equating due diligence with compliance is an approach many audit committees pursue with regard to safety risk but which is now effectively prohibited by statute law in most Australian jurisdictions.

This article first appeared on Sourceable (no longer available).

‘Due Diligence’ continues to expand in legislation

The changes set in motion by the 2011 National Model Work Health and Safety legislation are becoming apparent. Designers, owners, operators, regulators and the Courts are beginning to come to terms with the WHS Act’s imposed duties for organisations’ officers to ‘exercise due diligence’ in their safety risk management processes.

Due diligence is also a concept in both environmental protection and the broader context of sustainability, one of a number of parallels with health and safety. It is closely linked to how we view environmental impacts as part of the Technological Wager. That is, “society … betting on the success of future innovations to bail us out of problems created by present innovations”, as recently expounded by Adam Briggle in ‘A Field Philosopher’s Guide to Fracking’. One’s willingness to accept longer odds will reduce what one considers diligent at the time of the wager. That is, if we’re more confident of dealing with the mess we make now in the future, we may accept fewer or less effective precautions against the mess in the first place.

The recent amendments to Queensland’s Environmental Protection Act introduced (inter alia) a ‘due diligence’ test which the Department of Environment and Heritage Protection can implement when determining if a party took all reasonable steps to comply with their environmental obligations under the Act. Madeline Smith of Herbet Smith Freehills notes that amongst other matters it raises a range of questions as to what constitutes reasonable due diligence for an investor, financier or parent company with respect to, for instance, a subsidiary or investment company’s environmental obligations.

We watch these developments with interest.

Sustainability Due Diligence

Australian parliaments – supported by decisions of the High Court – have been encouraging the adoption of due diligence as a general concept to be applied throughout Australian society.

For example, due diligence in legislation is now called up by the Corporations Act (Cth) legislation, environmental legislation (e.g. NSW and Vic), model WHS legislation and Rail Safety National law etc.

In addition, earlier decisions of the High Court have been endorsed the idea. For example, the judges of the High Court unanimously agreed with the NSW Court of Appeal in 1980 [1] that due diligence as called up in the Hague Rules (to which Australia is a signatory) meant due care against negligence.

Due diligence is a legal concept. It represents an aspect of moral philosophy, that is, how the world ought to be and how humanity should behave in order to bring this about.

In practice, it seems to be an implementation of the ethic of reciprocity, often referred to as the Golden Rule in most philosophies and religions. Essentially, this means treat others as you would expect to be treated by them, or, do unto others as you would have done unto you. At least, that is what Lord Atkin indicated in Donaghue vs Stevenson (1932) [2].

In court this seems to be often tested (with the benefit of hindsight) in the form of the reasonable man test, meaning what would a reasonable man have done in the same circumstances. This is a complex idea as an American law professor notes [3]:

"The reasonable person is not any particular person or an average person… The reasonable person looks before he leaps, never pets a strange dog, waits for the airplane to come to a complete stop at the gate before unbuckling his seatbelt, and otherwise engages in the type of cautious conduct that annoys the rest of us… “This excellent but odious character stands like a monument in our courts of justice, vainly appealing to his fellow citizens to order their lives after his own example."

Much of all this is summarised in the Engineers Australia Safety Case Guideline (3rd edition), which is being launched at the National Convention in Melbourne this month. But what does all this mean and where are we heading, at least as engineers?

As something of an intellectual exercise, an attempt to apply the anticipated requirements (the logical consequence set) of recent Australian legislation and the common law decisions to date as they might be applied to global warming was presented last month by the authors at the NSW Regional Engineers Sustainability conference in Wollongong [4].

Our courts and parliaments require that, when it comes to the examination of human harm post event, all reasonable practicable precautions are demonstrated as being in place at the time decisions were made. To achieve this requires a number of steps.

The key steps for a due diligence argument are:

- A completeness argument as to why all key plausible critical issues were identified

- Identification of all physically possible precautions for each plausible critical issue

- Identification of which precautions in the circumstances are reasonable, balancing the significance of the risk vs. the effort required to achieve it (cost, difficulty and inconvenience and whatever other conflicting responsibilities the defendant may have).

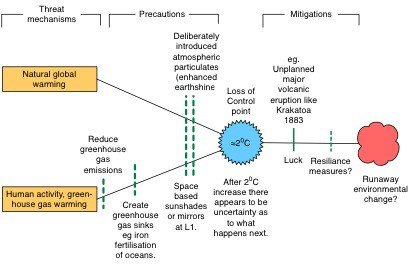

Based on CSIRO studies, it does seem that the planet is warming. Whether this is entirely due to human activity (greenhouse gas emissions) or natural forces is argued extensively, but there does seem to be general agreement that for the 6 billion people on planet Earth, more than two degrees Celsius is problematic. After that, no one’s too sure what might come next. A runaway temperature change that melts the three-kilometre deep Greenland ice sheet [5], for example, will result in a seven metre increase in sea levels, with dire consequences for low lying seaboard cities like Melbourne. This certainly seems a plausible, critical scenario and one that Australian governments should be seen to consider carefully.

Many options are being discussed to address the issue, including controlling carbon emissions, which has proved politically difficult and - if the planet is naturally warming - ineffective. A recent remarkable claim by Lockheed Martin’s “Skunkworks” that fusion energy is only five years [6] away would certainly address this.

There are, however, a number of other, apparently viable precautions of differing costs and effectiveness. The Krakatoa explosion [7] of 1883 apparently cooled the planet by about 1.2o degrees Celsius for a year as a result of the increased albedo effect (reflecting sunlight back in to space). We don’t yet seem to be able to predict such events in advance, so cooling the planet by that means would seem to more a matter of good luck than good governance.

Such precautions can be summarised in a threat-barrier diagram (TBD):

Central to a TBD is the loss of control (LoC) point. This is the point at which the laws of nature and man align. Legally, precautions act before the LoC whilst mitigations act after it.

There are a number of possible options available that would achieve a similar effect to a Krakatoa 1883 explosion, including pumping moisture into the air [8] to produce more reflective white clouds.

Sun shields such as the La Grangian L1 point between the Earth and the sun [9] would be effective too. Another method, possibly the cheapest and most effective of the lot, seems to be the fertilisation of the Southern Ocean [10] to create carbon absorbing algal blooms which would both cool the planet and act as a carbon sink, thereby de-acidifying the oceans.

According to Treasury [11], the Victorian desalination plant has presently cost the Victorian taxpayer $5.7 billion despite the fact that no water has been purchased. The reason for the plant's construction seems to based on a due diligence argument.

At the time of the decision, much of Australia had experienced a 10-year drought. If this had continued for another 10 years, the possibility of a major Australian population centre running out of water was deemed quite plausible. As state cabinet had the means within its power to ensure that this could not happen, it was done, even if it more likely than not will never be needed.

$5.7 billion is a lot of money. Many of the ideas mentioned to address global warming apparently could be implemented for such a sum. If so, it would appear to be within the power of the Victorian parliament and society to prevent a plausible catastrophic flooding of Melbourne due to runaway global warming.

Provided the science and numbers are right (and it is crucial that this be verified and validated), a perpetuation of the due diligence approach would seem to require the Victorian parliament to investigate and potentially act to protect Melbourne – and incidentally cool the whole planet.

References:

[1] Shipping Corporation of India Ltd. v. Gamlen Chemical Co. A/Asia. Pty. Ltd. [1980] HCA 51; (1980) 147 CLR 142

[2] See http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKHL/1932/100.html viewed 17 July 2013

[3] J M Feinman (2010). Law 101. Everything You Need to Know About American Law. Oxford University Press. Page 159

[4] See http://www.engineersaustralia.org.au/events/nsw-regional-convention-sustainable-regional-engineering

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greenland_ice_sheet viewed 7nov14

[6] http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/health-science/lockheed-martin-unveils-miniature-nuclear-fusion-power-generator/story-e6frg8y6-1227092587574?nk=4536f2c5e9e39c3c7dd336b0aae01f5c viewed 7nov14

[7] See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1883_eruption_of_Krakatoa viewed 7nov14.

[8] See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:SPICE_TESTBED_-_DEPLOYED_POSITION.jpg#filehistory viewed 7nov14, for an example.

[9] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_sunshade viewed 7nov14.

[10] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ocean_fertilization and http://www.acecrc.org.au/Research/Ocean%20Fertilisation and http://marineecology.wcp.muohio.edu/climate_projects_04/productivity/web/ironfert.html viewed 3nov14

[11] http://www.dtf.vic.gov.au/Infrastructure-Delivery/Public-private-partnerships/Projects/Victorian-Desalination-Plant viewed 3nov14.

This article first appeared on Sourceable.

Out of the Vault

A recent ABC News article mentions citywide tributes to one of Melbourne’s most famous and controversial sculptures, Vault, more popularly known as the ‘Yellow Peril’. The sculpture was removed from City Square following community and political opposition – Queen Elizabeth is said to have asked if it could be painted "a more agreeable colour" – and it was stored and installed at a progressive number of locations until reaching its current home at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art.

Vault at ACCA. (Photo source)

However architectural tributes to the sculpture have apparently arisen in a number of public artworks, including RMIT University and the Melbourne International Gateway. The Vault’s sculptor, Ron Robertson-Swann, also worked with Melbourne City Council to embed a reference to the sculpture into Swanson Street tram stops.

The tram stop tribute to Vault. (Photo source)

Of this project, Robertson-Swann said "That was one of the hardest design jobs I've ever done … Everything you did, oh my God, you couldn't do that [because of] health and safety”, with the result being "gentle and timid suggestions of fragments of Vault".

This shows a common problem arising from hazard-based risk management approaches, such as that espoused by AS31000. The issue arises from the cognitive and cultural differences between judgment and compliance, between art and function.

Hazard-based safety risk approaches look at a scenario and ask: “What could go wrong? What are we doing about this? Is it safe enough? Is the risk low enough?” This approach does identify safety issues and measures to address them. However, it also tends to push away new ideas and approaches, the result of a focus on ways in which these questions have previously been signed off – e.g. company procedures and industry technical standards.

A precaution-based safety risk approach, in contrast, looks first at the goals of the endeavor. Provided it is not considered prohibitively dangerous, it asks: “What safety measures should be in place so that we can move forward?” Precaution-based assessment is options, rather than hazard-based, and can thus effectively examine innovative suggestions as well as current practice, while maintaining a clear view of the overall goals of the process.

This is an especially powerful technique in design safety assessments. It allows artists, architects, engineers, constructors, owners, operators and maintainers to all put forward their various concerns and suggestions in a common framework. This enhances communication between stakeholders, and lets project leaderships teams make decisions that clearly address and explain their consideration of the diverse requirements of any multi-discipline project.

In the case of the Swanson Street tram stops, it may be that the use of a precaution-based design safety process which considered the safety and artistic goals as both key to the project success, rather than in opposition, may have led to a stronger artistic outcome without sacrificing safety.

For more detail on this approach read R2A’s Safety Due Diligence White Paper.

Tough Times Ahead for the Construction Sector?

The Construction Risk Management Summit organised by Expotrade was held in Melbourne on April 1 and 2, playing host to a diverse range of speakers and messages.

Possibly the most common message from academic speakers at the Construction Risk Management Summit was that the majority of projects do not come in on time or budget. In fact, many suffered from a major cost blowouts rate of nearly 100 per cent, with a wide array of reasons blamed for this issue.

The single biggest factor, which was identified by the majority of speakers, was failures in relation to upfront design. Typically, 80 per cent of the project cost is established at this phase. As a consequence, if errors occur during this phase of the project, additional expenses becomes a necessary, often quality controlled outcome. The solution to this issue was to have designers to focus on the long term operational performance, say at least 10 years operation, rather than just on practical completion.

This had several flow-on implications which were expanded upon by subsequent speakers. Knowing who the stakeholders are is critical. Stakeholders need to be understood and perhaps ranked in different ways, for example, as decision makers, interested parties and neighbours, lobby groups or as just acting in the public interest. This requires a culture of listening, which is an area the construction business should be encouraged to address.

Other speakers noted that the culture of the construction business could be changed, with safety in design identified as one cultural change that had occurred in recent times.

It was also noted that competitive pressures are still on the increase in the industry. Lowest tender bidding meant that corporate survival required "taking a chance" on contingencies in relation to risks that one could only hope would never eventuate.

If the construction market continues to shrink, more and more tenderers will be bidding for fewer and fewer jobs, with the final result being greater collective risk taking, or even an increasing likelihood of unethical behaviour.

This article first appeared on Sourceable. (No longer available)