ALARP vs SFAIRP revisited

The ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) versus SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable) debate appears to continue in many places, for example, AS/NZS2885.6:2018 Pipeline Safety Management. The current position of many is that SFAIRP equals ALARP and that any view to the contrary is just arguing about the number of angels on a pinhead.Nothing could be further from the truth. For engineers, the meaning is in the method; results are only consequences.

SFAIRP represents a fundamental paradigm shift in engineering philosophy and the way engineers are required to conduct their affairs.

It represents a drastically different way of dealing with future uncertainty. It represents the move from the limited hazard, risk and ALARP analysis approach to the more general designers’ criticality, precaution and SFAIRP approach.

That is, from:Is the problem bad enough that we need to do something about it?To:Here’s a good idea to deal with a critical issue, why wouldn’t we do it?

Paradigm is a much misused word and it is perhaps necessary to clarify what it means. In Thomas Kuhn’s seminal work, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, a paradigm is a universally recognised knowledge system that for a time providea model problems and solutions to a community of practitioners. He provides a notable series of scientific turning points associated with names like Copernicus, Newton, Lavoisier and Einstein. His point is that a new theory or approach is not accepted by the current practitioners since the theory often affects the work of a specialist group on whom the new theory impinges. And in doing so, reflects on much of the work that group has already completed. Its assimilation requires reconstruction of the prior approach and a re-evaluation of prior fact that is seldom completed by a single individual. In fact, it usually requires a generational shift.SFAIRP is paramount in Australian WHS legislation and has flowed into Rail and Marine Safety National law, amongst others. In Victoria, SFAIRP has now been incorporated into Environmental legislation. And, apart from the fact that SFAIRP is absolutely endemic in Australian legislation with manslaughter provisions to support it proceeding apace, SFAIRP is just a better way to live. It presents a positive, outcome driven design approach, always testing for anything else that can be done rather than trusting an unrepeatable (and therefore unscientific) estimation of rarity for why you wouldn’t.

If you’d like to hear Richard & Gaye discuss SFAIRP versus ALARP, check the below podcast episode.

Registration of Engineers (Victoria) & Why it's Important

The Engineers Registration Bill (Victoria) received Royal Assent on 3 November. This has always been a philosophically challenging matter for engineers. Many believe that it will stifle innovation in a shallow attempt to improve the status of engineers. Certainly, its implementation will be complex if the Queensland model is taken, as an example.

The primary reason for the registration of engineers is to protect the community and employers from unscrupulous and/or incompetent individuals claiming to be engineers.

The immediate purpose is to protect life, critical infrastructure and essential services.

Practically this comes down to ensuring that certain critical decisions must be transparently and diligently made by clearly identified responsible individuals, who recognise the possibility of their own negligence (you can’t always be right) with appropriate professional indemnity insurances, either by themselves or via their employers.

Such individuals include:

- Structural, civil and geotechnical engineers, for footings and structures including houses, high rise buildings, bridges, tunnels, dam design and operation, port and harbour design and the like;

- Mechanical engineers for high-rise lifts, cranes, boilers and pressure vessels, aircraft, road, rail and vehicle certification, high security bio-containment, defence munitions safety, pipelines etc;

- Fire Engineers for fire safe designs (hydraulic calculations, fire resistance, and the like);

- Chemical engineers, for process design particularly, to avoid major environmental contamination, toxic gas clouds, explosions and detonations;

- Electrical engineers, particularly for power station, substation and high voltage operations, and electrical safety generally;

- Mining engineers for underground, open cut and tailings dams’ safety and certification; and

- Aviation engineers for aircraft certification and naval architects for ship certification.

Historically, Engineers Australia has attempted to do this by ensuring, as far as possible, that such engineers have:

- Passed a recognised engineering course;

- Have relevant experience and continuing education; and

- Comply with The Code of Ethics which means at least ensuring that community safety is paramount, practicing within their area of competence, not accepting kick-backs (s/he who pays you is the client), being responsible for their own negligence (appropriate insurances) and giving credit where credit is due.

This 100-year-old view compares favourably with current financial governance being uncovered in the recent Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry.

Presently, these requirements only apply to the one third of engineers who choose to be members of Engineers Australia. But registration, supported by a Code of Conduct, should address this deficiency.

As for us at R2A, we are members of Engineers Australia and practice in accord with the Code of Ethics oulined above. But, we also believe practising to these standards is the right thing to do!

Why the philosophy of compliance will always fail

A very popular pastime of Australian parliaments is to pass legislation and regulation on the basis that, once it becomes the law, everyone will comply and it will, therefore, be effective.A concomitant result is that many boards and their legal advisers conduct compliance audits to confirm that these legal obligations have been met and, having done so, declare that they are ethically robust, safe and societally responsible.This is a flawed philosophy at many levels.

-

First, the sheer number and extent of laws and regulations in Australia means that the actual possibility of demonstrating compliance with each and every one is a logical impossibility.

Conceptually, the philosophy of compliance suggests that the more laws and regulations the better, even if the cost to demonstrate compliance continues to increase.

-

Second, in safety terms, mere compliance can never make anything safe.

It is simply not possible for our parliaments and regulators to predict in advance all the possible existing concerns, let alone the circumstances of possible future problems.The objective should be to understand the purpose of something and to meet that need. Compliance is a secondary aspect.For a simple example: Pool fencing is designed to prevent children drowning, not to satisfy a building surveyor, although this may be necessary to satisfy society that it has been done properly.

-

Third, compliance has always been about ensuring minimums; controlling the worst excesses.

It is seldom about promoting the best that we-can-do.The behaviour of the financial sector, the sex scandals in religious orders and the mistreatment in aged care are cases in point. From a societal viewpoint, the horrendous matters reported in the various Royal Commissions simply ought not to have happened.But, will increased legislation and regulation prevent such dreadful things from re-occurring in the future? Or is there a better way?

Interestingly, the engineers seem to have always understood this.

The Code of Ethics of Engineers Australia has always emphasised that the interest of society comes before sectional interests.These basic understandings, as articulated, for example, by the managing director of a major Australian Consulting Engineering firm to a young engineer in the 1970s, include:

1. S/he who pays you is your client.

A simple rule. Often overlooked. Having a building certifiers paid for by the developer easily leads to lazy certification. A better approach would be to have the (future) owners pay for the certification. The possibility of a conflict of interest would be functionally reduced by design.

2. No kickbacks.

A lot or rules and regulations can be written about this. But if a professional adviser does not understand that a hidden commission is morally indefensible, there is a problem that no amount of regulation can fix. It may not be illegal to pay a spotter’s fee, but it’s certainly morally suspect.

3. Stick to your area of competence.

Don’t provide advice or opinions without adequate knowledge. Does this really need legislation and regulation?

4. Be responsible for your own negligence.

That is, recognise that you can’t always be right. Amongst other things, advisers need professional indemnity insurance, in part, to remedy honest mistakes.

5. Give credit where credit is due.

That is, don’t take credit for what others have achieved.

There is nothing new or novel about these basic understandings. But rather than legislating and regulating with a list of things not-to-do, it may be better to re-design the commercial environment so that virtuous behaviour is rewarded.Certainly, the old ACEA (Association of Consulting Engineers, Australia) used to do this. ACEA required that member firms were controlled by directors who were bound by the Engineers’ Code of Ethics.This meant that in the event of a decision between the best interests of the consulting firm and the client’s, the client’s interests normally held sway.

What are the Unintended Consequences of Due Diligence?

In my article Why Risk changed to Due Diligence & Why it’s become so Important, I briefly described the principle of; do unto others, otherwise known as the Principle of Reciprocity, and how Governments in Australia have incorporated the concept in legislation in the form of due diligence. With this in mind, it’s important to consider the unintended consequences of due diligence.

Below I examine two examples of the logical consequence set of the due diligence approach.

Unlicensed persons doing electrical work

Due diligence in safety legislation requires that risks be eliminated, so far as is reasonably practical, or if they can't be eliminated, reduced so far as is reasonably practical.The bane of electrical regulators in Australia is the home handyman working in a roof space and fiddling with the 240V conductors. Death is a regular result. The fatalities arising from the home insulation Royal Commission also spring to mind.Most of us have been replacing dichroic downlights in our existing houses with energy efficient 12V LEDs. And although it may be unreasonable to retrospectively replace the 240V wiring in the roof space with extra low voltage (ELV) conductors for existing structures, it is obviously quite achievable for new dwellings. And if all the wiring in the roof is 12 or 24 V (and all the 240V wiring is in the walls) then the possibility of being electrocuted in a roof space is pretty much eliminated, which is the purpose of the legislation. In fact, the most likely thing to happen next is that all lights will get smart and be provided with power over Ethernet (PoE) (up to 48V).What all this means is that, in the event of an electrocution in a roof space, the designer of domestic dwellings that did not install ELV lighting in houses built since the commencement of the WHS legislation will, most likely be considered reckless in terms of the legislation since the elimination option is obviously reasonably practicable.

Global warming & the City of Melbourne

Does the Parliament of Victoria have a duty of care to Melbournians? Not just current, but future ones? The High Court of Australia has been clear that future generations (yet unborn) can be considered neighbours for the purposes of having a duty of care.If that's the case, when it comes to global warming (whether it's real or not is an interesting question but it's certainly credible) if the Greenland ice sheet melts, which is arguably what will happen if temperatures increase by two or three degrees, the sea level in Port Phillip Bay will rise about seven meters.Seven meters in a low-lying city like Melbourne would be significant. You could forget Flinders Street Station as your meeting point.Due diligence is all about options analysis for credible (foreseeable) hazards and I can tell you of at least three, just from a preliminary internet search.

- NASA wants to put in space sun shields and actually shield the planet from the sun. This option is in the $trillions, probably, but quite do-able.

- Cambridge University engineers want to increase earthshine by squirting vapor at high altitude increasing the cloud cover and, thereby, reflecting more energy away from the planet, which is entirely practical. This would probably cost $20B or so to cool the planet.

- The cheapest option is one which an American decided to try by taking a ship load of fertilizers out to sea and dumping it into the ocean to see what would happen. The result was a plankton bloom.Applying this idea in the Southern Ocean, you would get lots of plankton, and then lots of krill, and consequently, fat whales. But much of the plankton and krill would die before being consumed and sink to the Antarctic ocean floor thereby creating a giant carbon sink. To cool the planet (and de-acidify the oceans as well) will be less than probably $10B or so based on the last estimate I’ve seen.

The Victorian desalination plant cost over $5B and ultimately $18B or so all up during the 27 year lifetime of the plant. It was built to deal with the credible, critical threat of Melbourne running out of water if a 10 year drought persisted.All this means that the Government of Victoria has the resources to implement at least one of the options described above. And following its own legislation, it seems the government has committed itself to seriously considering if it should cool the planet to protect the citizens of Melbourne against flooding due to the credible possibility of global warming.These examples, along with many more, along with the tools we use to engineer due diligence, are detailed in our Due Diligence Engineering textbook that’s available to purchase here.If you’d like our assistance with any upcoming due diligence, contact us for a friendly chat.

Why Risk changed to Due Diligence & Why it’s become so Important

At our April launch of the 11th Edition of Engineering Due Diligence textbook, I discussed how the service of Risk Reviews has changed to Due Diligence and why it’s become so important for Australian organisations.

But to start, I need to go back to 1996. The R2A team and I were conducting risk reviews on large scale engineering projects, such as double deck suburban trains and traction interlocking in NSW, and why the power lines in Tasmania didn't need to comply with CB1 & AS7000, and why the risk management standard didn't work in these situations.And, what we kept finding was that as engineers we talked about high consequence, low likelihood (rare) events, and then we’d argue the case with the financial people over the cost of precautions we suggested should be in place, we’d always lose the argument.However, when lawyers were standing with us saying, 'what the engineers are saying makes sense - it's a good idea', then the ‘force’ was with us and what we as engineers suggested was done.

As a result, in the 2000s we started flipping the process around and would lead with the legal argument first and then support this with the engineering argument. And every time we did that, we won.

It was at this stage we started changing from Risk and Reliability to Due Diligence Engineers, because it was always necessary to run with the due diligence first to make our case.

Since we made this fundamental change in service and became more involved in delivering high level work, that is, due diligence, it has also become part of the Australian governance framework.Due diligence has become endemic in Australian legislation. In corporations’ law; directors must demonstrate diligence to ensure, for example, that a business pays its bills when they fall due. It's in WHS Legislation. It's in Environmental Legislation. Due diligence is now required to demonstrate good corporate governance.And what I mean by that is that there’s a swirl of ideas that run around our parliaments. Our politicians pick the ideas they think are good ones. One of these was the notion of due diligence that was picked up from the judicial, case (common) law system.There’s an interesting legal case on the topic going back to 1932: Donoghue vs Stevenson; the Snail in the Bottle. When making his decision, the Brisbane-born English law lord, Lord Aitken said that the principle to adopt is; do unto others as you would have done unto you.The do unto others principle (the principle of reciprocity) was nothing new; it’s been a part of major philosophies and religions for over 2000 years.Our parliamentarians took the do unto others idea and incorporated it into Acts, Regulations and Codes of Practice as the notion of Due Diligence.That is, due diligence has become endemic in Australian legislation and in case law, to the point that it has become, in the philosopher Immanuel Kant’s terms, a categorical imperative. That is, our parliamentarians and judges seem to have decided that due diligence is universal in its application and creates a moral justification for action. This also means the converse, that failure to act demands sanction against the failed decision maker. I discuss this further along with two examples in the article What are the Unintended Consequences of Due Diligence.To learn more about Engineering Due Diligence and the tools we teach at our two-day workshop, you can purchase our text resource here.If you’d like to discuss we can help you make diligent decisions that are safe, effective and compliant, we’d love to hear from you. Contact us today.

Worse Case Scenario versus Risk & Combustible Cladding on Buildings

BackgroundThe start of 2019 has seen much media attention to various incidents resulting from, arguably, negligent decision making.One such incident was the recent high-rise apartment building fire in Melbourne that resulted in hundreds of residents evacuated.The fire is believed to have started due to a discarded cigarette on a balcony and quickly spread five storeys. The Melbourne Fire Brigade said it was due to the building’s non-combustible cladding exterior that allowed the fire to spread upwards. The spokesperson also stated the cladding should not have been permitted as buildings higher than three storeys required a non-combustible exterior.Yet, the Victorian Building Authority did inspect and approve the building.Similar combustible cladding material was also responsible for another Melbourne based (Docklands) apartment building fire in 2014 and for the devastating Grenfell Tower fire in London in 2017 that killed 72 people with another 70 injured.This cladding material (and similar) is wide-spread across high-rise buildings across Australia. Following the Docklands’ building fire, a Victorian Cladding Task Force was established to investigate and address the use of non-compliant building materials on Victorian buildings.Is considering Worse Case Scenario versus Risk appropriate?In a television interview discussing the most recent incident, a spokesperson representing Owners’ Corporations stated owners needed to look at worse case scenarios versus risk. He followed the statement with “no one actually died”.While we agree risk doesn’t work for high consequence, low likelihood events, responsible persons need to demonstrate due diligence for the management of credible critical issues.The full suite of precautions needs to be looked at for a due diligence argument following the hierarchy of controls.The fact that no one died in either of the Melbourne fires can be attributed to Australia’s mandatory requirement of sprinklers in high rise buildings. This means the fires didn’t penetrate the building. However, the elimination of cladding still needs to be tested from a due diligence perspective consistent with the requirements of Victoria’s OHS legislation.What happens now?The big question, beyond that of safety, is whether the onus to fix the problem and remove / replace the cladding is now on owners at their cost or will the legal system find construction companies liable due to not demonstrating due diligence as part of a safety in design process?Residents of the Docklands’ high-rise building decided to take the builder, surveyor, architect, fire engineers and other consultants to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) after being told they were liable for the flammable cladding.Defence for the builder centred around evidence of how prevalent the cladding is within Australian high-rise buildings.The architect’s defence was they simply designed the building.The surveyor passed the blame onto the Owners’ Corporation for lack of inspections of balconies (where the fire started, like the most recent fire, with a discarded cigarette).Last week (at the time of writing), the apartment owners were awarded damages for replacement of the cladding, property damages from the fire and an increase in insurance premiums due to risk of future incidents. In turn, the architect, fire engineer and building surveyor have been ordered to reimburse the builder most of the costs.Findings by the judge included the architect not resolving issues in design that allowed extensive use of the cladding, a failure of “due care” by the building surveyor in its issue of building permit, and failure of fire engineer to warn the builder the proposed cladding did not comply with Australian building standards.Three percent of costs were attributed to the resident who started the fire.Does this ruling set precedence?Whilst other Owners’ Corporations may see this ruling as an opportunity (or back up) to resolve their non-compliant cladding issues, the Judge stated they should not see it as setting any precedent.

"Many of my findings have been informed by the particular contracts between the parties in this case and by events occurring in the course of the Lacrosse project that may or may not be duplicated in other building projects," said Judge Woodward.

If you'd like to discuss how conducting due diligence from an engineering perspective helps make diligent decisions that are effective, safe and compliant, contact us for a chat.

Why your team has a duty of care to show they've been duly diligent

In October and November (2018), I presented due diligence concepts at four conferences: The Chemeca Conference in Queenstown, the ISPO (International Standard for maritime Pilot Organizations) conference in Brisbane, the Australian Airports Association conference in Brisbane (with Phil Shaw of Avisure) and the NZ Maritime Pilots conference in Wellington.

The last had the greatest representation of overseas presenters. In particular, Antonio Di Lieto, a senior instructor at CSMART, Carnival Corporation's Cruise ship simulation centre in the Netherlands. He mentioned that:

a recent judgment in Italian courts had reinforced the paramountcy of the due diligence approach but in this instance within the civil law, inquisitorial legal system.

This is something of a surprise. R2A has previously attempted to test ‘due diligence’ in the European civil (inquisitorial) legal system over a long period by presenting papers at various conferences in Europe. The result was usually silence or some comment about the English common law peculiarities.

The aftermath of the accident at the port of Genoa. Credit: PA

The incident in question occurred on May 2013. While executing the manoeuvre to exit the port of Genoa, the engine of the cargo ship “Jolly Nero” went dead. The big ship smashed into the Control Tower, destroying it, and causing the death of nine people and injuring four.

So far the ship’s master, first officer and chief engineer have all received substantial jail terms, as has the Genoa port pilot. It seems that a failure to demonstrate due diligence secured these convictions

And there are two more ongoing inquiries:

- One regards the construction of the Tower in that particular location, an investigation that has already produced two indictments; and

- The second that focuses on certain naval inspectors that certified ship.

It's important to realise everyone involved -- the bridge crew, the ship’s engineer, ship certifier, marine pilot, and the port designer -- all have a duty of care that requires, post event, they had been duly diligent.

Are you confident in your team's diligent decision making? If not, R2A can help; contact us to discuss how.

What you can learn about Organisational Risk Culture from the CBA Prudential Inquiry

R2A was recently commissioned to complete a desktop risk documentation review in the context of the CBA Prudential Inquiry of 2018. The review has provided a framework for boards across all sectors to consider the strength of their risk culture. This has been bolstered by the revelations from The Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry.

Specifically, R2A was asked to provide commentary on the following:

- Overall impressions of the risk culture based on the documentation.

- To what extent the documents indicate that the organisation uses organisational culture as a risk tool.

- Any obvious flaws, omissions or areas for improvement

- Other areas of focus (or questions) suggested for interviews with directors, executives and managers as part of an organisational survey.

What are the elements of good organisational risk culture?

Organisations with a mature risk culture have a good understanding of risk processes and interactions. In psychologist James Reason’s terms[1], these organisations tend towards a generative risk culture shown in James Reason’ s table of safety risk culture below.

| Pathological culture | Bureaucratic culture | Generative culture |

|

|

|

How different organisational cultures handle safety information

Key attributes include:

- Risk management should be embedded into everyday activities and be everyone’s responsibility with the Board actively involved in setting the risk framework and approving all risk policy. Organisations with a good risk culture have a strong interaction throughout the entire organisation from the Board and Executive Management levels right through to the customer interface.

- The organisation has a formal test of risk ‘completeness’ to ensure that no credible critical risk issue has been overlooked. To achieve this, R2A typically use a military intelligence threat and vulnerability technique. The central concept is to define the organisation’s critical success outcomes (CSOs). Threats to those success outcomes are subsequently identified and are then systematically matched against the outcomes to identify critical vulnerabilities. Only the assessed vulnerabilities then have control efforts directed at them. This prevents the misapplication of resources to something that was really only a threat and not a vulnerability.

- Risk decision making is done using a due diligence approach. This means ensuring that all reasonable practicable precautions are in place to provide confidence that no critical organisational vulnerabilities remain. Due diligence is demonstrated based on the balance of the significance of the risk vs the effort required to achieve it (the common law balance). This is consistent with the due diligence provisions of the Corporations, Safety (OHS/WHS) and environmental legislation.

Risk frameworks and characterisation systems such as the popular 5x5 risk matrix (heat map) approach are good reporting tools to present information and should be used to support the risk management feedback process. Organisations should specifically avoid using ‘heatmaps’ as decision making tool as that is inconsistent with fiduciary, safety and environmental legislative requirements.

Risk Appetite Statements for commercial organisations have become very fashionable. The statement addresses the key risk areas for the business and usually considers both the possibility of risk and reward. However, for some elements such as compliance (zero tolerance) and safety (zero harm), risk appetite may be less appropriate as the consequences of failure are so high that there is simply no appetite for it. For this reason, R2A prefers the term risk position statements rather than risk appetite statements.

To get a feel for the risk culture within an organisation, R2A suggest conducting generative interviews with recognised organisational ‘good’ players rather than conducting an audit.

We consider generative interviews to be a top-down enquiry and judgement of unique organisations rather than a bottom-up audit for deficiencies and castigation of variations for like organisations. R2A believes that the objective is to delve sufficiently until evidence to sustain a judgement is transparently available to those who are concerned. (Enquiries should be positive and indicate future directions whereas audits are usually negative and suggest what ought not to be done).

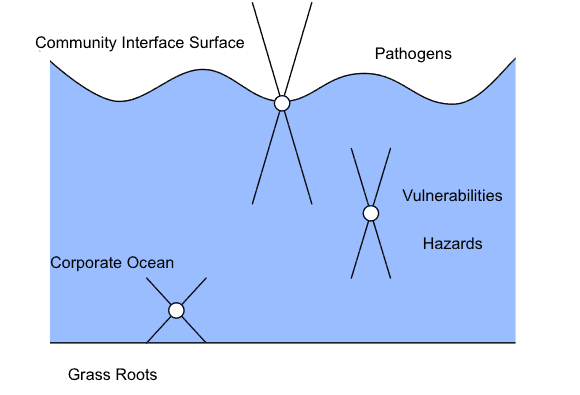

Interview depth

Individuals have different levels of responsibility in any organisation. For example, some are firmly grounded with direct responsibility for service to members. Others work at the community interface surface with responsibilities that extend deep into the organisation as well as high into the community. We understand that the idea is that a team interviews recognised 'good players' at each level of the organisation. If a commonality of problems and, more particularly, solutions are identified consistently from individuals at all levels, then adopting such solutions would be fast, reliable and very, very desirable.

Other positive feedback loops may be created too. The process should be stimulating, educational and constructive. Good ideas from other parts of the organisation ought to be explained and views as to the desirability of implementation in other places sought.

If a health check on your organsational risk culture or a high level review of your enterprise risk management system is of interest, please give us a call to discuss further on 1300 772 333 or head to our contact page and fill in an enquiry.

[1] Reason, J., 1997. Managing the Risks of Organisational Accidents. Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited. Page 38.

Managing Critical Risk Issues: Synthesising Liability Management with the Risk Management Standard

The importance of organisations managing critical risk issues has been highlighted recently with the opening hearings of the coronial inquest into the 2016 Dreamworld Thunder River Rapids ride tragedy that killed four people.

In a volatile world, boards and management fret that some critical risk issues are neither identified nor managed effectively, creating organisational disharmony and personal liabilities for senior decision makers.

The obligations of WHS – OHS precaution based legislation conflict with the hazard based Risk Management Standard (ISO 31000) that most corporates and governments in Australia mandate. This is creating very serious confusion, particularly with the understanding of economic regulators.

The table below summarises the two approaches.

| Precaution-based Due Diligence (SFAIRP) | ≠ | Hazard-based Risk Management (ALARP) | |

| Precaution focussed by testing all practicableprecautions for reasonableness. | Hazard focussed by comparison to acceptable ortolerable target levels of risk. | ||

| Establish the context

Risk assessment (precaution based): Identify credible, critical issues Identify precautionary options Risk-effort balance evaluation Risk action (treatment) |

Establish the context Risk assessment (hazard based): (Hazard) risk identification (Hazard) risk analysis (Hazard) risk evaluation Risk treatment |

||

| Criticality driven. Normal interpretation ofWHS (OHS) legislation & common law |

Risk (likelihood and consequence) driven Usual interpretation of AS/NZS ISO 31000[1] |

||

A paradigm shift from hazard to precaution based risk assessment

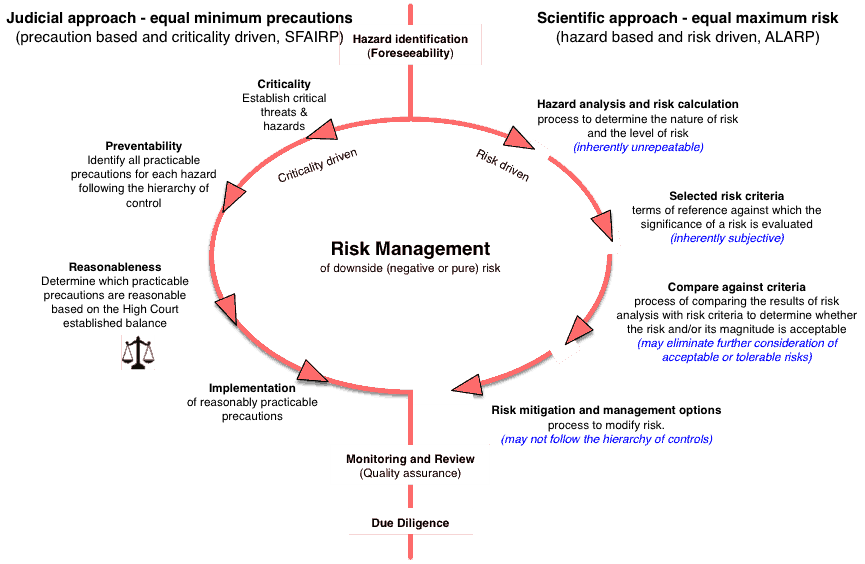

Decision making using the hazard based approach has never satisfied common law judicial scrutiny. The diagram below shows the difference between the two approaches. The left hand side of the loop describes the legal approach which results in risk being eliminated or minimised so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP) such as described in the model WHS legislation.

Its purpose is to demonstrate that all reasonable practicable precautions are in place by firstly identifying all possible practicable precautions and then testing which are reasonableness in the circumstances using relevant case law.

The level of risk resulting from this process might be as low as reasonably practicable (ALARP) but that’s not the test that’s applied by the courts after the event. The courts test for the level of precautions, not the level of risk. The SFAIRP concept embodies this outcome.

The target risk approach, shown on the right hand side, attempts to demonstrate that an acceptable risk level associated with the hazard has been achieved, often described as as low as reasonably practicable or ALARP. But there are major difficulties with each step of this approach as noted in blue.

SFAIRP v ALARP

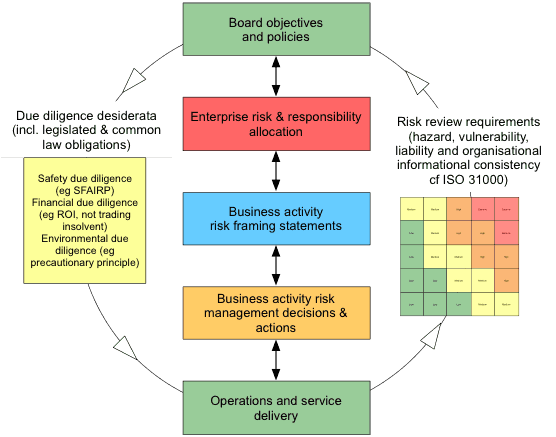

However, there is a way forward that usefully synthesises the two approaches, thereby retaining the existing ISO 31000 reporting structure whilst ensuring a defensible decision making process.

Essentially, high consequence, low likelihood risk decisions are based on due diligence (for example, SFAIRP, ROI, not trading whilst insolvent and the precautionary principle, consistent with the decisions of the High Court of Australia) whilst risk reporting is done via the Risk Management Standard using risk levels, heat maps and the like. This also resolves the tension between the use of the concepts of ‘risk appetite’ (very useful for commercial decisions) and ‘zero harm’ (meaning no appetite for inadvertent deaths).

Essentially the approach threads the work completed (often) in silos by field / project staff into a consolidated framework for boards and executive management.

If you'd like to discuss how we can assist with identifying and managing critical risk issues within your organisation, we'd love to hear from you. Head to our contact page to organise a friendly chat.

[1] From the definition in AS/NZS ISO 31000: 2.24 risk evaluation process of comparing the results of risk analysis (2.21) with risk criteria (2.22) to determine whether the risk (2.1) and/or its magnitude is acceptable or tolerable.

Energy Safety Report Released

The Release of the Final Report and Government Response - Review of Victoria's Electricity and Gas Network Safety Framework has occurred and is available at https://engage.vic.gov.au/electricity-network-safety-review.R2A is quoted a number of times in the report.Two of the key recommendations, supported in principle by the government, are:

34 All energy safety legislation should be consolidated in a single new energy safety Act, replacing the Gas Safety Act 1997, Electricity Safety Act 1998, those elements of the Pipelines Act 2005 that relate to safety, and the Energy Safe Victoria Act 2005.35 The general safety duties within the new consolidated energy safety legislation should be based around a consistent application of the principle that risks should be reduced so far as is “reasonably practicable” aligning with the definition adopted in the Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004.

Recommendation 35 does not sit well with a significant number of Australian Standards which continue to use an ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) approach, supported by a target or tolerable level of risk and safety instead of the ‘so far as is reasonably practicable’ approach of the 2004 Victoria OHS Act and the model WHS legislation adopted in almost all other Australian jurisdictions, and in New Zealand.Such standards particularly include AS2885 (the pipeline standard), AS5577 (electricity network safety), AS (IEC) 61508 (functional safety) and its derivatives.R2A has previously commented on this issue. We (also) regularly have had to overturn the ALARP approach in these standards based on relevant legal advice.I'll be presenting the basis for this need to the Chemeca 2018 conference in Queenstown on 2nd October in a session entitled: Gas Pipelines and the Changing Face of Australian Energy Regulation.

Australian Standard 2885, Pipeline Safety & Recognised Good Practice

Australian guidance for gas and liquid petroleum pipeline design guidance comes, to a large extent, from Australian Standard 2885. Amongst other things AS2885 Pipelines – Gas and liquid petroleum sets out a method for ensuring these pipelines are designed to be safe.

Like many technical standards, AS2885 provides extensive and detailed instruction on its subject matter. Together, its six sub-titles (AS2885.0 through to AS2885.5) total over 700 pages. AS2885.6:2017 Pipeline Safety Management is currently in draft and will likely increase this number.

In addition, the AS2885 suite refers to dozens of other Australian Standards for specific matters.

In this manner, Standards Australia forms a self-referring ecosystem.

R2A understands that this is done as a matter of policy. There are good technical and business reasons for this approach;

- First, some quality assurance of content and minimising repetition of content, and

- Second, to keep intellectual property and revenue in-house.

However, this hall of mirrors can lead to initially small issues propagating through the ecosystem.

At this point, it is worth asking what a standard actually is.

In short, a standard is a documented assembly of recognised good practice.

What is recognised good practice?

Measures which are demonstrably reasonable by virtue of others spending their resources on them in similar situations. That is, to address similar risks.

But note: the ideas contained in the standard are the good practice, not the standard itself.

And what are standards for?

Standards have a number of aims. Two of the most important being to:

- Help people to make decisions, and

- Help people to not make decisions.

That is, standards help people predict and manage the future – people such as engineers, designers, builders, and manufacturers.

When helping people not make decisions, standards provide standard requirements, for example for design parameters. These standards have already made decisions so they don’t need to be made again (for example, the material and strength of a pipe necessary for a certain operating pressure). These are one type of standard.

The other type of standard helps people make decisions. They provide standardised decision-making processes for applications, including asset management, risk management, quality assurance and so on.

Such decision-making processes are not exclusive to Australian Standards.

One of the more important of these is the process to demonstrate due diligence in decision-making – that is that all reasonable steps were taken to prevent adverse outcomes.

This process is of particular relevance to engineers, designers, builders, manufacturers etc., as adverse events can often result in safety consequences.

A diligent safety decision-making process involves,:

- First, an argument as to why no credible, critical issues have been overlooked,

- Second, identification of all practicable measures that may be implemented to address identified issues,

- Third, determination of which of these measures are reasonable, and

- Finally, implementation of the reasonable measures.

This addresses the legal obligations of engineers etc. under Australian work health and safety legislation.

Standards fit within this due diligence process as examples of recognised good practice.

They help identify practicable options (the second step) and the help in determining the reasonableness of these measures for the particular issues at hand. Noting the two types of standards above, these measures can be physical or process-based (e.g. decision-making processes).

Each type of standard provides valuable guidance to those referring to it. However the combination of the self-referring standards ecosystem and the two types of standards leads to some perhaps unintended consequences.

Some of these arise in AS2885.

One of the main goals of AS2885 is the safe operation of pipelines containing gas or liquid petroleum; the draft AS2885:2017 presents the standard's latest thinking.

As part of this it sets out the following process.

- Determine if a particular safety threat to a pipeline is credible.

- Then, implement some combination of physical and procedural controls.

- Finally, look at the acceptability of the residual risk as per the process set out in AS31000, the risk management standard, using a risk matrix provided in AS2885.

If the risk is not acceptable, apply more controls until it is and then move on with the project. (See e.g. draft AS2885.6:2017 Appendix B Figures B1 Pipeline Safety Management Process Flowchart and B2 Whole of Life Pipeline Safety Management.)

But compare this to the decision-making process outlined above, the one needed to meet WHS legislation requirements. It is clear that this process has been hijacked at some point – specifically at the point of deciding how safe is safe enough to proceed.

In the WHS-based process, this decision is made when there are no further reasonable control options to implement. In the AS2885 process the decision is made when enough controls are in place that a specified target level of risk is no longer exceeded.

The latter process is problematic when viewed in hindsight. For example, when viewed by a court after a safety incident.

In hindsight the courts (and society) actually don’t care about the level of risk prior to an event, much less whether it met any pre-determined subjective criteria.

They only care whether there were any control options that weren’t in place that reasonably ought to have been.

‘Reasonably’ in this context involves consideration of the magnitude of the risk, and the expense and difficulty of implementing the control options, as well as any competing responsibilities the responsible party may have.

The AS2885 risk sign-off process does not adequately address this. (To read more about the philosophical differences in the due diligence vs. acceptable risk approaches, see here.)

To take an extreme example, a literal reading of the AS2885.6 process implies that it is satisfactory to sign-off on a risk presenting a low but credible chance of a person receiving life-threatening injuries by putting a management plan in place, without testing for any further reasonable precautions.[1]

In this way AS2885 moves away from simply presenting recognised good practice design decisions as part of a diligent decision-making process and, instead, hijacks the decision-making process itself.

In doing so, it mixes recognised good practice design measures (i.e. reasonable decisions already made) with standardised decision-making processes (i.e. the AS31000 risk management approach) in a manner that does not satisfy the requirements of work health and safety legislation. The draft AS2885.6:2017 appears to realise this, noting that “it is not intended that a low or negligible risk rank means that further risk reduction is unnecessary”.

And, of course, people generally don’t behave quite like this when confronted with design safety risks.

If they understand the risk they are facing they usually put precautions in place until they feel comfortable that a credible, critical risk won’t happen on their watch, regardless of that risk’s ‘acceptability’.

That is, they follow the diligent decision-making process (albeit informally).

But, in that case, they are not actually following the standard.

This raises the question:

Is the risk decision-making element of AS2885 recognised good practice?

Our experience suggests it is not, and that while the good practice elements of AS2885 are valuable and must be considered in pipeline design, AS2885’s risk decision-making process should not.

[1] AS2885.6 Section 5: “... the risk associated with a threat is deemed ALARP if ... the residual risk is assessed to be Low or Negligible”

Consequences (Section 3 Table F1): Severe - “Injury or illness requiring hospital treatment”. Major: “One or two fatalities; or several people with life-threatening injuries”. So one person with life-threatening injuries = ‘Severe’?

Likelihood (Section 3 Table 3.2): “Credible”, but “Not anticipated for this pipeline at this location”,

Risk level (Section 3 Table 3.3): “Low”.

Required action (Section 3 Table 3.4): “Determine the management plan for the threat to prevent occurrence and to monitor changes that could affect the classification”.

Risk Engineering Body of Knowledge

Engineers Australia with the support of the Risk Engineering Society have embarked on a project to develop a Risk Engineering Book of Knowledge (REBoK). Register to join the community.

The first REBoK session, delivered by Warren Black, considered the domain of risk and risk engineering in the context risk management generally. It described the commonly available processes and the way they were used.

Following the initial presentation, Warren was joined by R2A Partner, Richard Robinson and Peter Flanagan to answer participant questions. Richard was asked to (again) explain the difference between ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) and SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable).

The difference between ALARP and SFAIRP and due diligence is a topic we have written about a number of times over the years. As there continues to be confusion around the topic, we thought it would be useful to link directly to each of our article topics.

Does ALARP equal due diligence, written August 2012

Does ALARP equal due diligence (expanded), written September 2012

Due Diligence and ALARP: Are they the same?, written October 2012

SFAIRP is not equivalent to ALARP, written January 2014

When does SFAIRP equal ALARP, written February 2016

Future REBoK sessions will examine how the risk process may or may not demonstrate due diligence.

Due diligence is a legal concept, not a scientific or engineering one. But it has become the central determinant of how engineering decisions are judged, particularly in hindsight in court.

It is endemic in Australian law including corporations law (eg don’t trade whilst insolvent), safety law (eg WHS obligations) and environmental legislation as well as being a defence against (professional) negligence in the common law.

From a design viewpoint, viable options to be evaluated must satisfy the laws of nature in a way that satisfies the laws of man. As the processes used by the courts to test such options forensically are logical and systematic and readily understood by engineers, it seems curious that they are not more often used, particularly since it is a vital concern of senior decision makers.

Stay tuned for further details about upcoming sessions. And if you are needing clarification around risk, risk engineering and risk management, contact us for a friendly chat.

Rights vs Responsibilities in Due Diligence

A recent conversation with a consultant to a large law firm described the current legal trend in Melbourne, notably that rights had become more important than responsibilities.This certainly seems to be the case for commercial entities protecting sources of income, as particularly evidenced in the current banking Royal Commission (Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry).It seems that, in the provision of financial advice, protecting consulting advice cash flow was seen as much more important than actually providing the service.Engineers probably have a reverse perspective. As engineers deal with the real (natural material) world, poor advice is often very obvious. When something fails unexpectedly, death and injury are quite likely.Just consider the Grenfell Tower fire in London and the Lacrosse fire in Melbourne. This means that for engineers at least, responsibilities often overshadow rights.This is a long standing, well known issue. For example, the old ACEA (Association of Consulting Engineers, Australia) used to require that at least 50% of the shares of member firms were owned by engineers who were members in good standing of Engineers Australia (FIEAust or MIEAust) and thereby bound by Engineers Australia’s Code of Ethics.The point was to ensure that, in the event of a commission going badly, the majority of the board would abide by the Code of Ethics and look after the interests of the client ahead of the interests of the shareholders.Responsibilities to clients were seen to be more important than shareholder rights, a concept which appears to be central to the notion of trust.

Role & Responsibility of an Expert Witness

Arising from a recent expert witness commission, the legal counsel directed R2A’s attention to Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001} NSWCA 305 (14 September 2001), which provides an excellent review of the role and responsibility of an expert witness, at least in NSW.

Arising from an expert witness commission, relevant counsel has directed R2A’s attention to Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001} NSWCA 305 (14 September 2001), which provides an excellent review of the role and responsibility of an expert witness, at least in NSW. The case cites many authorities outlining these responsibilities. For example, (at 59) it indicates that for the professor’s report to be useful, it is necessary for it to comply with the prime duty of experts in giving opinion evidence, that is, to furnish the trier of fact with criteria enabling evaluation of the validity of the expert’s conclusions. This is alternatively stated in a number of different places and ways, for example (at 60);Courts cannot be expected to act upon opinions the basis of which is unexplained. And again (at 69); Before a court can assess the value of an opinion it must know the facts upon which it is based. If the expert has been misinformed about the facts or has taken irrelevant facts into consideration or has omitted to consider the relevant ones, the opinion will be valueless. In our judgement, counsel calling an expert should in examination in chief ask his witness to state the facts upon which his opinion is based. It is wrong to leave the other side to elicit the facts by cross-examination. In keeping with what constitutes expert witness opinion in the above, it remains a source of frustration to R2A that legal decisions can be so opaque to non-lawyers that it requires legal counsel to direct R2A to the best decisions to provide insight in to the workings of our courts. From R2A’s perspective, judgements should ideally be available in plain English on searchable databases, so that the information is readily available to all. Apart from making the life of due diligence engineers easier, it would also enhance the value of the work of the courts to the society they serve. Interestingly, David Howarth (professor of Cambridge Law and Public Policy) whom R2A sponsored to Melbourne last year (2017), made a passing remark that there was a reason for this complexity. It is to do with the fact that judicial decisions can effectively become retrospective in the common law. To avoid this outcome, judges ensure that the detailed circumstances of each decision is spelt out so that any such retrospectivity can be curtailed. Editor's Note: This article was originally posted on 1 July 2014 and has been updated for accuracy and relevance.

Engineering As Law

Both law and engineering are practical rather than theoretical activities in the sense that their ultimate purpose is to change the state of the world rather than to merely understand it. The lawyers focus on social change whilst the engineers focus on physical change.It is the power to cause change that creates the ethical concerns. Knowing does not have a moral dimension, doing does. Mind you, just because you have the power to do something does not mean it ought to be done but conversely, without the power to do, you cannot choose.Generally for engineers, it must work, be useful and not harm others, that is, fit for purpose. The moral imperative arising form this approach for engineers generally articulated in Australia seems to be:

- S/he who pays you is your client (the employer is the client for employee engineers)

- Stick to your area of competence (don’t ignorantly take unreasonable chances with your client’s or employer’s interests)

- No kickbacks (don’t be corrupt and defraud your client or their customers)

- Be responsible for your own negligence (consulting engineers at least should have professional indemnity insurance)

- Give credit where credit is due (don’t pinch other peoples ideas).

Overall, these represent a restatement of the principle of reciprocity, that is, how you would be expected to be treated in similar circumstances and therefore becomes a statement of moral law as it applies to engineers.

How did it get to this? Project risk versus company liability

Disclosure: Tim Procter worked in Arup’s Melbourne office from 2008 until 2016.Shortly after Christmas a number of media outlets reported that tier one engineering consulting firm Arup had settled a major court case related to traffic forecasting services they provided for planning Brisbane’s Airport Link tunnel tollway. The Airport Link consortium sued Arup in 2014, when traffic volumes seven months after opening were less than 30% of that predicted. Over $2.2b in damages were sought; the settlement is reportedly more than $100m. Numerous other traffic forecasters on major Australian toll road projects have also faced litigation over traffic volumes drastically lower than those predicted prior to road openings.Studies and reviews have proposed various reasons for the large gaps between these predicted and actual traffic volumes on these projects. Suggested factors have included optimism bias by traffic forecasters, pressure by construction consortia for their traffic consultants to present best case scenarios in the consortia’s bids, and perverse incentives for traffic forecasters to increase the likelihood of projects proceeding past the feasibility stage with the goal of further engagements on the project.Of course, some modelling assumptions considered sound might simply turn out to be wrong – however, Arup’s lead traffic forecaster agreeing with the plaintiff’s lead counsel that the Airport Link traffic model was “totally and utterly absurd”, and that “no reasonable traffic forecaster would ever prepare” such a model indicates that something more significant than incorrect assumptions were to blame.Regardless, the presence of any one of these reasons would betray a fundamental misunderstanding of context by traffic forecasters. This misunderstanding involves the difference between risk and criticality, and how these two concepts must be addressed in projects and business.In Australia risk is most often thought of as the simultaneous appreciation of likelihood and consequence for a particular potential event. In business contexts the ‘consequence’ of an event may be positive or negative; that is, a potential event may lead to better or worse outcomes for the venture (for example, a gain or loss on an investment).In project contexts these potential consequences are mostly negative, as the majority of the positive events associated with the project are assumed to occur. From a client’s point of view these are the deliverables (infrastructure, content, services etc.) For a consultant such as a traffic forecaster the key positive event assumed is their fee (although they may consider the potential to make a smaller profit than expected).Likelihoods are then attached to these potential consequences to give a consistent prioritisation framework for resource allocation, normally known as a risk matrix. However, this approach does contain a blind spot. High consequence events (e.g. client litigation for negligence) are by their nature rare. If they were common it is unlikely many consultants would be in business at all. In general, the higher the potential consequence, the lower the likelihood.This means that potentially catastrophic events may be pushed down the priority list, as their risk (i.e. likelihood and consequence) level is low. And, although it may be very unlikely, small projects undertaken by small teams in large consulting firms may have the potential to severely impact the entire company. Traffic forecasting for proposed toll roads appears to be a case in point. As a proportion of income for a multinational engineering firm it may be minor, but from a liability perspective it is demonstrably critical, regardless of likelihood.There are a range of options available to organisations that wish to address these critical issues. For instance, a board may decide that if they wish to tender for a project that could credibly result in litigation for more than the organisation could afford, the project will not proceed unless the potential losses are lowered. This may be achieved by, for example, forming a joint venture with another organisation to share the risk of the tender.Identifying these critical issues, of course, relies on pre-tender reviews. These reviews must not only be done in the context of the project, but of the organisation as a whole. From a project perspective, spending more on delivering the project than will be received in fees (i.e. making a loss) would be considered critical. For the Board of a large organisation, a small number of loss-making projects each year may be considered likely, and, to an extent, tolerable. But the Board would likely consider a project with a credible chance, no matter how unlikely, of forcing the company into administration as unacceptable.This highlights the different perspectives at the various levels of large organisations, and the importance of clear communication of each of their requirements and responsibilities. If these paradigms are not understood and considered for each project tender, more companies may find themselves in positions they did not expect.Also published on:https://sourceable.net/how-did-it-get-to-this-project-risk-vs-company-liability/

The Art of Communicating Engineering Judgement

Tim Procter shares his experience as a graduate engineer developing engineering judgement and his approach to communicating this knowledge to various stakeholders. This article was originally published at Engineering Education Australia.

As a graduate engineer (some years ago) moving from university to the workplace I was surprised to discover just how vast and varied engineering knowledge actually is. After completing an intensive degree and gaining what felt like a good understanding of engineering fundamentals, it came as something of a surprise to realise that becoming expert in just one engineering sub-sub-discipline could truly take a lifetime.

Science fiction legend, Arthur C. Clarke noted that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. To the qualified but inexperienced engineer that I was, a senior engineer discussing advanced engineering knowledge appeared quite the same; the outputs were comprehensible, but not their derivation. Such knowledge was generally referred to as demonstrating ‘engineering judgement’.

Engineering judgement is used when making a decision. It involves an engineer weighing up, in their own mind, the pros and cons of the potential courses of action being considered. This process may be formal, intuitive or deliberate or, in most cases, an intricate combination of the three.

As a graduate I regarded this engineering judgement with a sense of awe, as I considered the years of experience my seniors wielded when pronouncing how the engineered world should be. Surely, I thought, one day in the (distant) future my engineering judgement will arrive. And then I too will have the knowledge!

Oddly enough, I found personal development tends not to work this way. My engineering judgement gradually developed with my experience as I dealt with problems of greater complexity. I discovered that I understood the decision required, the options available, and the best course of action, but the act of explaining the decision was often more difficult than simply knowing the answer.

This knowing/telling paradox gives a clue as to the source of my graduate self’s confusion and awe of my senior colleagues’ wisdom. While the best solution may have been found, a problem persists; sometimes this judgement must be explained to a non-technical layperson, including graduate engineers.

Explaining engineering judgement to non-technical persons happens in a range of contexts – financial, managerial, corporate, governmental, legal, and the wider community. It is especially important for these stakeholders to understand the decision-making processes when dealing with safety, the environment, project management, operations and a whole host of other engineering considerations. This means that engineering jargon and equations will often work against the goal of communication.

The most effective approach I have found to communicate engineering judgement is to explain the options considered, their gradual exclusion, and the specific reasons each excluded option was considered unsuitable. It requires a clear explanation of critical success factors and how each option supports or hinders each of these goals. This best reflects the engineering process, where much of the time the ‘best’ option is actually the ‘least worst’ option, given the constraints it must meet and the corresponding trade-offs in time, cost, quality, and efficiency.

I find this process is generally understood by non-technical persons and helps prompt structured and useful questions from listeners: Why was this option not appropriate? How were the specific benefits of this option considered? This provides a good enquiry framework for engineering graduates and others to both understand and develop their own engineering judgement.

It is critical for graduates to develop their engineering judgement and the ability to communicate it. It brings confidence to both the engineer and their stakeholders, as each better understands the others’ needs and decisions. It is, in many ways, the single most important skill I have developed in my career, and something that each day I practise, in both senses of the word.

My advice for graduates is to take any opportunity to do the same. Make your best decisions for the problems you face, and then discuss your judgements with your managers, mentors and teammates. And when more complex engineering problems arise you’ll be able to not only solve them but also explain them. And that’s something that every engineer should be able to do.

Also published at:

https://eea.org.au/insights-articles/art-communicating-engineering-judgement

https://frontier.engineersaustralia.org.au/news/the-art-of-communicating-engineering-judgement/

2017: The Year in Review

It’s hard to believe that 2017 is coming to a close and 2018 is almost here. As part of our end of year wrap up, here are some of the highlights that we would like to share with you.

In February R2A together with the Victorian Bar had the pleasure of presenting Cambridge Reader in Law and former British MP, Professor David Howarth for a special session, co-chaired by the Victorian Bar and Engineers Australia, exploring his latest book, Law as Engineering.

Professor Howarth’s essential point in his book is that these days most lawyers don’t litigate. Rather, they design social constructs such as contracts, companies, treaties and wills to facilitate their clients’ wishes. This is similar to how engineers design physical constructs to satisfy their clients’ desires.

David’s event sparked useful and interesting discussions between the engineering and legal professions.

Gaye's role on the Powerline Bushfire Safety Committee continued this year. Gaye’s role is to provide risk management and best practice advice.

We were privileged to work with many clients throughout the year. Here are a few of the interesting projects completed during the year.

INTERESTING PROJECTS

Bicycle Access Management Review. Earlier this year R2A assisted Queensland’s Department of Transport and Main Roads (TMR) with the development, testing and implementation of a risk assessment methodology for bicycle access management. Following a series of information-gathering tasks, R2A developed a proposed SFAIRP[1] decision-making process for bicycle access management on state-controlled roads. TMR is currently preparing a supporting policy for state-wide implementation.

Asset Risk Management Framework Review. R2A completed a review to develop an asset safety risk management framework consistent with the requirements of the Work Health and Safety Act (WHS) 2012, the TasNetworks Risk Management Framework (2015) and the TasNetworks Asset Management Plan (2015) whilst simultaneously taking into account the requirements of Tasmania’s electricity safety regulator (the Department of Justice) and the national electricity economic regulator (the AER).

Gold Coast Desalination Plant Access Review. R2A undertook a commission to conduct a safety due diligence review of the Gold Coast Desalination Plant access arrangements to the high-pressure areas whilst the plant is producing water.

State Emergency Risk Assessment Review. This project was undertaken to confirm the appropriateness of the State’s priority emergency risks, the controls in place and their effectiveness as well as and if required revise the risk characterisation in line with the updated National Emergency Risk Assessment Guidelines (NERAG) 2014.

Rail Project Business Case Reviews. R2A completed a number of business case reviews were this year for PTV and Trasport for Victoria, including the Safer Country Crossings and DDA Access Improvements Programs.

Plant and Equipment Review. R2A were engaged by DEDJTR to review its plant and equipment safety management systems at 8 key Department research farms. This provided a basis for a larger Department program to enhance its safe and efficient management of physical assets.

Fire Loss Risk Methodology Review. The purpose of R2A’s review was to ‘test’ the proposed methodology and to provide advice as to its effectiveness or otherwise of demonstrating ‘as far as practicable’ in the management of bushfire risk, particularly with regard to the question of disproportionality.

The Grimes Review

On 19 January 2017, the Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change announced an independent review of Victoria’s Electricity Network Safety Framework, to be chaired by Dr Paul Grimes. On 5 May 2017, the Minister announced an expansion to the Review’s Terms of Reference to include Victoria’s gas network safety framework. R2A provided submissions for both gas and electrical safety, and met with Dr Grimes twice.

Pleasingly, from R2A’s perspective, the recommendation in the interim report stated that the decision-making criteria for safety should be consistent with that of the 2004 OHS act, that is, a precautionary approach that uses the SFAIRP principle rather than an ALARP principle using target levels of risk.

In coming to this view Dr Grimes comments favourably on the R2A understanding of issues involved.

The final report is expected to be released early next year.

CONFERENCES

Earlier this year Tim presented at the Fire Australia Conference in Sydney on The Legal Context to QRA. Whilst Gaye presented her paper on How safe is safe enough? Effective Safety Frameworks at EECon in Melbourne. Richard also presented to two groups of marine pilots on pilotage safety due diligence at SmartShip.

We have availability for similar opportunities next year. Drop us a line if you have an event coming up.

MEDIA

Richard and Tim continued to write for Sourceable this year:

- Engineering’s Golden Rule (March 2017)

- Design Safety Decisions Don’t Disappear (May 2017)

- Scientific Management and the AER (July 2017)

- Regulators Put Cost Before Safety (August 2017)

- Explaining Engineering Judgement (November 2017)

EDUCATION

From an education perspective, Richard delivered numerous public and in-house courses on Engineering Due Diligence as well as continuing to deliver the Swinburne post-graduate unit Introduction to Risk & Due Diligence with Gaye and Tim both presenting guest lectures.

The 2-day joint R2A/EEA engineering due diligence workshop was again successful this year and will continue in 2018. This workshop is aimed at aspiring directors and senior managers.

[1] “So far as is reasonably practicable”, as required by the 2011 Work Health and Safety Act.

Update on Victoria’s Energy Safety Framework Review

On 19 January 2017, the Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change announced an independent review of Victoria’s Electricity Network Safety Framework, to be chaired by Dr Paul Grimes. On 5 May 2017, the Minister announced an expansion to the Review's Terms of Reference to include Victoria’s gas network safety framework.The interim report was released in October and can be viewed at: https://engage.vic.gov.au/application/files/6915/0942/0613/Interim_Report_-_Review_of_Victorias_Electricity_and_Gas_Network_Safety_Framework.pdfR2A provided submissions for both gas and electrical safety which have previously been blogged at:

- Gas Supplementary Issues Paper - Review of Victoria's Electricity and Gas Network Safety Framework

- Review of Victoria's Electricity and Gas Network Safety Framework

From R2A’s reading of the interim report, the primary recommendation is that there should be a single piece of energy safety legislation that covers electricity, gas and pipelines, all to be administered by a single agency, Energy Safe Victoria.Pleasingly, from R2A’s perspective, the decision making criteria for safety should be consistent with that of the 2004 OHS act, that is, a precautionary approach that uses the SFAIRP principle rather than an ALARP principle using target levels of risk.In coming to this view Dr Grimes comments favourably on the R2A understanding of issues involved. He notes that R2A in its submission to the Review expressed a view that there needs to be clarity and consistency around the question of what constitutes “ reasonably practicable ” and, in addition, the language that is adopted to express the objective of the safety framework.

Nevertheless, the methodological distinction between the target risk and a precaution based approaches, and the other important practical implications identified by R2A, are highly relevant to the Review’s consideration and have helped inform its assessment of leading practice. (footnote on page 72)

Dr Grimes concludes that:

The Review is persuaded by the arguments that a pure target risk approach, while having some theoretical elegance, is less robust in practice than a precaution - based approach…(page 73) … the Review is proposing a draft recommendation that this definition be formally adopted for electricity and gas network safety.

The R2A Board considers the adoption of the precaution based approach to be an outstanding outcome and congratulates Dr Grimes on his acuity.The cutoff date for comment on the interim report of the Review of Victoria’s Electricity and Gas Network Safety Framework is the 27th November.

Should you attend the Engineering Due Diligence Workshop?

An introduction to the concept of Engineering Due Diligence

Engineering is the business of changing things, ostensibly for the better. The change aspect is not contentious. Who decides what’s ‘better’ is the primary source of mischief.

In a free society, this responsibility is morally and primarily placed on the individual, subject always to the caveat that you shouldn’t damage your neighbours in the process. Otherwise you can pursue personal happiness to your heart’s content even though this often does not make you as happy as you’d hoped. And it becomes rapidly more complex once collective cooperation via immortal legal entities known as corporations came to the fore as the best way to generate and sustain wealth. This is particularly significant for engineers as the successful implementation of big ideas requires large scale cooperative effort to the possible detriment of other collectives.

The rule of law underpins the whole social system. It is the method by which harm to others is minimised consistent with the principle of reciprocity (the golden rule – do unto others as you would have done unto you) prevalent in successful, prosperous societies. In Australia it has been implemented via the common law and increasingly, in statute law. Company directors, for example, have to be confident that debts can be paid when they fall due (corporations law), workers (and others) should not be put unreasonably at risk in the search for profits (WHS law) and the whole community should be protected against catastrophic environmental harm (environmental legislation). It is unacceptable for drink-drivers to kill and injure others, the vulnerable to be exploited or the powerful to be immune from prosecution. Everyone is to be equal before the law.

Provided such outcomes are achieved, the corporation and the individuals within them are pretty much free to do as they please. Monitoring all these constraints and ensuring the balance between individual freedoms and unreasonable harm (safety, environmental and financial) to others has become the primary focus of our legal system.

But the world is a complex place and its difficult to be aways right particularly when dealing with major projects. But it is entirely proper to try to be right within the limits of human skill and ingenuity. The legal solution to address all this has been via the notion of ‘due diligence’ and the ‘reasonable person’ test.

Analysing complex issues in a way that is transparent to an entire organisation, the larger society and, if necessary, the courts can be perplexing. Challenges arise in organisations when there are competing ideas of better, meaning different courses of action all constrained with finite resources. This EDD workshop provides a framework for the various internal and external stakeholders to listen to, understand and decide on the optimal course of action taking into account safety, environmental, operational, financial and other factors.

To be ‘safe’, for example, requires that the laws of nature be effectively managed, but done in a way that satisfies the laws of man, in that order.

Engineering Due Diligence Workshop

The learning method at the R2A & EEA public workshops follows a form of the Socratic ‘dialogue’. Typical risk issues and the reasons for their manifestation are articulated and exemplar solutions presented for consideration. The resulting discussion is found to be the best part for participants as they consider how such approaches might be used in their own organisation or project/s.

Current risk issues of concern and exemplar solutions include:

- Project schedule and cost overruns. This is much to do with the over-reliance on Monte Carlo simulations and the Risk Management Standard which logically and necessarily overlook potential project show-stoppers. A proven solution using military intelligence techniques will be articulated. This has never failed in 20 years with projects up to $2.5b.

- Inconsistencies between the Risk Management Standard and due diligence requirements in legislation, particularly the model WHS Act. A tested solution that integrates the two is presented, as is now being implemented by many major Australian and New Zealand organisations, shown diagrammatically below.

- Compliance does not equal due diligence. Solutions are provided to avoid over reliance on legal compliance as an attempt to demonstrate due diligence. It also demonstrates how a due diligence approach facilitates innovation.

- The SFAIRP v ALARP debate. Model solutions presented (if relevant to participants) including marine and air pilotage, seaport and airport design (airspace and public safety zones), power distribution, roads, rail, tunnels and water supply.

Participants are also encouraged to raise issues of concern. To enable open discussion and explore possible solutions, the Chatham House Rule applies to participants’ remarks meaning everyone is free to use the information received without revealing the identity or affiliation of the speaker.