Conversations Engineers need to have about Risk Management

The theme for Season 5 of our Risk! Engineers Talk Governance podcast is ‘Conversations engineers need to have about risk management’. These are sometimes hard conversations and not necessarily popular conversations, but we think it is important that they are had.

The reason we bring up the need for these discussions is that the notion and understanding of risk appears to have changed over time.

Richard and I have always understood risk to be a negative concept and have focussed our careers on addressing downside safety, environmental, project and enterprise / organisational issues.

However, the idea of upside risk and reward seems to have become the focus in the engineering space recently. For example, the title of the upcoming Engineers Australia Risk Engineering Conference is Turning Risks into Opportunities.

This is a very commercial or project view on risk, where there are upside benefits. Most engineers are focussed on safety risk which is all downside risk (zero harm), for which there is no risk appetite.

There is also the feeling that risk is stifling innovation and that some risk needs to be taken to achieve great outcomes. R2A would consider this entrepreneurship rather than risk management. Risk in this sense would be a by-product of innovation, but the consequences would just be commercial / financial, repetitional or not achieving the desired outcomes.

Late last year, R2A delivered a course on Risk Management to Chartered Engineer Assessors. We were horrified to hear that only a very small number of candidates interviewed for chartered status thought that the Work Health and Safety (WHS) Legislation (OHS Act in Victoria) was relevant to their role and they had to worry about risk management.

As due diligence engineers, this is more than alarming. Safety is paramount. The role of engineers is to ensure that all reasonable, practicable precautions / controls are in place for all credible critical safety issues.

This applies to the entire engineering process – design, operation, maintenance, etc. Innovation can be achieved for safety issues and it is usually in the controls / precautions that can be put forward.

For example, in the pilotage of large vessels into ports, Personal Pilotage Units were new technology 30 years ago. They were big and bulky and difficult for pilots (on big vessels) to get on and off ships. Today they are very accurate devices and the size of a laptop or tablet. This technology has now become good practice and is typically used by most marine pilotage organisations if there is a need.

There have also been significant improvements to safety in the mining industry, where now the explosive charges are let off from a remote site control room rather than have a miner underground to do that task.

R2A doesn’t think that rewards and opportunities should be the main focus of risk management in an engineering sense, especially when dealing with real engineering problems.

Safety cannot be ignored. If something is prohibitively dangerous, then it must be stopped.

For all other safety issues, all reasonably practicable precautions must be in place. Controls are assessed based on the balance of the significance of the risk verses the effort required to reduce it.

Environmental issues are in a similar category to safety and, in Victoria, have the same legislative requirements.

Here are some helpful tips we recommend for engineers to manage risk:

Understand the legislative context / environment in which you work.

Criticality before risk always. Catastrophic events must be seen to have been properly managed.

Be diligent, you can’t always be right.

It’s all about design not risk assessment. Risk assessments are only used to test the value of a proposed control.

Standards are just a starting point. You must do better if you reasonably can.

Work collaboratively with key stakeholders (the parties that live or die by the result), not just interested parties.

WHS Legislation: The Glue That Binds Industries

Richard recently had an online session with a PhD candidate from ECU (Edith Cowan University) who was researching the integration of fire engineering and security concerns and how practitioners in the two domains ought to work together.

The session had Richard, as the fire engineer, and an ex-military security consultant. Somewhat to the surprise of the researcher, both Richard and the security adviser firmly agreed on the centrality of the WHS (in Vic OHS) legislation as the glue that bound the two domains together. The diagram that developed during the discussion is shown below.

That is, both the fire engineer and the security consultant agreed that the due diligence obligations of the WHS legislation forced congruence on both domains.

The best way forward was to have competent experts get together and work out what was best in design terms rather than trying to address the problem in silos, which is what was mostly occurring in industry.

This happened to parallel a discussion Richard recently had with our NZ associate, Dr Frank Stoks, who was acting as an expert witness into the death of a young man in Auckland. And that was that there are always competing objectives to do with foreshore amenity and views, verses a person falling into the water, etc. As a CPTED (Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design) practitioner, Frank held that IPTED (Injury Prevention Through Environmental Design) needs to work together and the only way to do that is to get all the key design players together to thrash out a solution.

Obviously the more complicated the problem the greater the conclave of expert designers would need to be in order to establish the balance of what was reasonable in the circumstances.

Major global IT outage

The importance of criticality (not risk) in due diligence

The recent major IT outage that affected systems around the world highlights the importance of criticality and resilience.

As due diligence engineers, if you have heard Richard and I talk before, we continually speak about the importance of criticality rather than risk. That is, those issues that are critical to your organisation regardless of the likelihood.

Richard and I were actually in the air, flying back from New Zealand when the failure occurred. We returned to see the chaos at airports around the world with cancelled flights as ticketing and check-in systems failed. Having to revert back to manual check-in seemed difficult, meaning that there wasn’t an effective back-up system in place.

It was apparently reported in the media that this outage was seen as an accident.

Yes, we agree that the event was not deliberate but it is certainly a foreseeable event that there could be an IT outage (for whatever reason), that has the potential to impact organisations. And therefore, we would not consider it an accident, but a credible critical threat.

Many of these critical issues in organisations are still being considered and managed on a risk basis, the simultaneous appreciation of likelihood and consequence. This is primarily being driven from the financial side of the business with organisations always trying to optimise return. What organisations try to do is achieve the greatest system availability at least cost.

Now the problem with that, of course, is that if you're relying on a single system, you can't gold plate that single system so that it will never fail. You just can't stop all single points of failure.

Gold plating can potentially provide some system resilience but it will never provide system redundancy. Therefore, if you're down to one system and it fails, then you must have a backup.

That means we are talking about system redundancy by making sure that you've got another independent system that doesn't rely on the primary system, so that in the event that the primary system does fail, there is a genuinely independent backup.

There are lots of different ways to do it. However, the only way we know to get high availability at low cost is have two redundant systems in parallel.

In conclusion, for organisations that rely on IT systems to deliver their products and services, such as airlines and health services, a major outage is a critical issue and must be (seen to be) managed accordingly from a due diligence perspective.

Global warming and Criticality & Design

Environmental Due Diligence

In the final episode of season 3 of our podcast, Risk! Engineers Talk Governance, Richard and I reflected on what appeared to be a common thread throughout the season which was criticality and design. With this context, we discussed climate change and environmental due diligence, and the example of global warming. This is a credible critical issue and if we take the due diligence design approach, you are basically asking what are the design options that can be put forward for this critical issue and which is/are reasonable in the circumstances.

Richard and I have used Melbourne as an example on a number of occasions and put the question forward:

Should the Victorian government (which has practicable options available and the resources to do so) protect Melbourne (a low-lying city) from rising sea levels?

Governance obligations require organisations and governments to make decisions regarding credible, critical risks, such as major flooding of a capital city from rising sea levels using the concept of due diligence.

The essential aspect of due diligence is that foreseeable harm to neighbours should be appropriately managed. Therefore, the first question is Can the concept of neighbour encompass future generations?

The High Court of Australia seems to think so and has noted [Deane J in Hawkins v Clayton (1988)]:

… a duty of care can be owed to a class of persons who are not yet born…

In 2004, the Victorian parliament passed the Occupational Health and Safety Act. Amongst other matters this requires all persons to eliminate hazards, so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP), and if this is not possible, to reduce risks so far as is reasonably practicable. The Act binds the Crown.

In 2018, the Victorian government passsed the Environment Protection Amendment Act 2018, which commenced on 1 July 2020. The cornerstone of the Environment Protection Amendment Act 2018 is the General Environmental Duty (GED). The GED adopts the SFAIRP principle used in the OHS Act, that is: to eliminate risks of harm to human health and the environment so far as reasonably practicable; and if it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate risks of harm to human health and the environment, to reduce those risks so far as reasonably practicable.

A breach of the GED could lead to criminal or civil penalties. This Act also binds the Crown.

Based on BoM and CSIRO studies it does seem that the planet is warming. Whether this is entirely due to human activity (greenhouse gas emissions) or natural forces is argued extensively. But there does seem to be general agreement that for the 6 billion people on planet Earth, more than a 2 degrees celsius increase is problematic. After that, no-one’s too sure what might come next.

A runaway temperature change that melts the 3km deep Greenland ice sheet, for example, will result in a 7m increase in sea levels, with incredible consequences for the residents of (relatively) low lying seaboard cities like Melbourne. This certainly seems a plausible, critical scenario and one that Australian governments should be seen to consider carefully.

Due diligence is all about what can be done (options analysis) rather than endlessly arguing over the detail of the actual degree of risk, particularly for high consequence, low likelihood events. Due diligence is output, not input, focused.

An internet search reveals that the number of options being discussed to address such an issue is quite numerous. These includec ontrolling carbon emissions, which has proved politically difficult and, if the planet is naturally warming, quite ineffective. The Krakatoa explosion of 1883 seems to have cooled the planet by about 1.2 degrees Celsius for a year as a result of the increased albedo effect (reflecting sunlight back into space). But we don’t yet seem to be able to predict such events in advance, so cooling the planet by that means would seem to be more a matter of good luck than good governance.

However, there are a number of other, apparently viable precautions of differing costs and effectiveness.

These include pumping moisture into the air (more white reflective clouds) that would achieve a similar effect to a Krakatoa 1883 explosion.

Sun shields at the La Grangian L1 point between the Earth and the sun would be effective too.

Possibly the cheapest option seems to be the fertilisation of the Southern Ocean to create carbon absorbing algal blooms which may cool the planet and also act as a carbon sink thereby de-acidifing the oceans. Such precautions can be summarised in a threat-barrier diagram (TBD), like that shown below.

Global warming threat-barrier diagram

From a due diligence perspective, the question is: Are any of these reasonable in the circumstances?

This is decided on the balance of the significance of the risk verses the effort required to reduce it. From Justice Sir Anthony Mason of the High Court of Australia in Wyong Shire Council v Shirt (1980):

The perception of a reasonable man’s response calls for a consideration of the magnitude of the risk and the degree of probability of its occurrence, along with the expense, difficulty and inconvenience of taking alleviating action and any other conflicting responsibilities which the defendant may have.

According to the Victorian Government department that is responsible for water (there have been a number of name changes over the years), the Victorian desalination plant has presently cost the Victorian taxpayer around $5.7 billion (without the purchase of any water). The reason for the need for the plant seems to be based on a due diligence argument. At the time of the decision, much of Victoria had experienced a 10 year drought. If this drought had continued for another 10 years, the possibility of Melbourne running out of water was deemed quite plausible.

As the state cabinet had within its power to ensure that this could not happen, then whatever was needed was done, even if it is more likely than not that it will never be needed.

$5.7 billion is a lot of money. Some of the ideas mentioned to address global warming apparently might be implemented for such a sum.

If so, it would appear to be within the power of the Victorian parliament to prevent a plausible catastrophic flooding of Melbourne due to run-away global warming.

In conclusion, provided the science and numbers are right (this would be very prudent to verify and validate), a perpetuation of the due diligence approach enshrined in Victorian OHS and environmental legislation would seem to require the Victorian parliament to investigate and potentially act to protect the residents (present and future) of Melbourne - and incidentally cool the entire planet.

How Councils can eliminate town planning disasters

Following our recent expert witness work at VCAT (Victorian Civil & Administrative Tribunal) regarding a residential re-development in the outer safety zone of a Major Hazard Facility, and the ruling that accepted our precautionary approach, we have been further discussing the critical role council play in eliminating town planning disasters.

The rise of WHS legislation mandates that there needs to be a positive demonstration of safety due diligence for major hazards such as dams, major hazard facilities and environmental hazards including bushfires, cyclones and floods, etc. Presently, the most robust and effective way to achieve this known to R2A is by the use of the safety case concept to demonstrate SFAIRP (that hazards have been eliminated or reduced so far as is reasonably practicable), that is, the rise of the SFAIRP safety case. SFAIRP is the ‘modern’ definition of ‘safe’.

The inclusion of criminal manslaughter provisions in safety legislation (which therefore includes dealing with hazards that were either known or ought to have been known) has reinforced this. It is now absolutely essential for anyone (especially officers as defined by corporations’ law) responsible for the management of any facility that can cause fatalities, like dams, major hazard facilities and the like or approving development in areas with known extreme environmental hazards, to positively demonstrate safety due diligence in a way that is scientifically defensible, organisationally useful, publicly digestible and will survive post-event legal scrutiny.

Note also that on 1 July 2021, Victoria commenced the SFARP provisions of the Environmental Protection Act 2017. Amongst other things, this Act imposes a general environmental duty (GED) on a person to minimise, as far as reasonably practicable (SFAIRP), risks or harm to human health and the environment (Section 25). Particularly, it further requires the person to eliminate such risks, and if not reasonably practicable to do so, to reduce them so far as reasonably practicable (Section 6). If not already, it appears to be only a matter of time that the SFA(I)RP concept will be entrenched in other legislation and regulatory instruments.

In this context, it is important to remember that legally, safety risk does not arise because something is inherently dangerous, which all dams, major hazard facilities and extreme environmental events potentially are; rather it arises because there are insufficient, inadequate or failed precautions, as determined by our courts, post event.

Following an event, the court is actually testing to see if there were any other controls or precautions suggested by the expert witnesses that were reasonably practicable in view of what was known at the time.

The point is that in safety terms, the OHS/WHS legislation is focussed at high consequence, low likelihood event and demand that all reasonably practicable precautions are in place rather than achieving a pre-event level of risk or safety. You don’t ignore the lesser problems but you just apply recognised good practice and move on. This will significantly reduce your workload.

After attending the International Public Works Conference recently in Melbourne, it occurred to me that there are great opportunities for councils to help build more resilient and robust communities as part of the town planning processes.

One of the key messages from the conference was ‘build back better’ and for there to be a shift in focus from recovery efforts following an incident to robust and resilient communities that can better withstand these credible but critical events.

There are two approaches that are commonly used in land use planning.

The target level of risk approach tends to sterilise planning areas from development and ignores the rare but catastrophic hazards. This is indefensible from a WHS/OHS perspective and just plain silly from an engineering design perspective. Any site has issues and for the design to be successful, all these must be addressed.

The alternate approach is the precautionary approach to land use planning. This approach encourages planners to test for effective risk control options for foreseeable credible critical (worst-case) severity events. This means that the closer to the hazard a structure is, the greater the precautions need to be. In principle, provided the level of protection is high enough, there are no limits to where a structure could be built in relation any credible critical hazard.

Just like any other environmental hazard including bushfire, flood, dam break, electrical blackout, cyclone, high pressure gas main rupture, major hazard exposures, communities need to design for resilience.

Work out the credible worst case scenario and design accordingly.

For example, golf course and open public spaces provide fire breaks to townships from bushfire risk rather than allowing residential building right to the bush fringe.

ISO 31000 the risk management standard - WHS/OHS legislation consequences

One of the most common questions we receive as due diligence engineers is around ISO 31000, the risk management standard and its consequences in relation to Australian and New Zealand WHS and OHS legislation.

ISO 31000 is a well-known and highly adopted risk management framework with the vision to make lives easier, safer and better. Specifically, the standard aims to provide “principles, a framework and a process for managing risk.

The problem from a due diligence perspective is this generalised standard can add confusion and a false sense of security for Australian organisations in terms of their governance processes and duty of care in relation to their obligations under health and safety legislation.

The OHS Act started in Victoria in 2004; the Model WHS Act commenced in most jurisdictions in 2011-2012, while Western Australia adopted it in 2022. New Zealand adopted it in 2015. The legislation is clear in its objectives that its purpose is to achieve the highest level of protection as is reasonably practicable for everyone.

The ISO 31000 process is contradictory to the WHS/OHS Act, at least when you're dealing with health and safety.

Unfortunately, this (similar) confusion is reflected throughout other Australian Standards. For example, there's no such thing as a target level or tolerable level of risk or safety. The legislation's clear you've got to achieve the highest level of protection as you reasonably can.

To illustrate this, the Standards' Australia handbook, "Managing health-and-safety related risks", importantly says:

"Contemporary WHS legislation does not prescribe an acceptable or tolerable level of risk. The emphasis is on the effectiveness of controls, not estimated risk levels. It may be useful to estimated risk level for the purposes such as communicating which risks are the most significant or prioritising risks within a risk treatment plan. In any case, care should be taken to avoid targeting risk levels that may prevent further risk minimisation efforts that are reasonably practical to implement."

This is an absolutely perfect re-statement of the intention of the Model WHS legislation.

Yet, the process encouraged by ISO 31000, the risk management standard states it’s (to) establish the context and do a (hazard-based) risk assessment– which is hazard risk identification, hazard risk analysis, hazard risk evaluation and then risk treatment.

The two concepts don't align.

If you look at the Network Safety Standard, AS 5577, which is mandated by many regulators, it tells you to use the ISO 31000 Risk Management standard approach whilst also saying at different times throughout the standard you shall, for example, initiate action so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP). It then goes on with all the things you should do. It also says you shall eliminate hazards so far as reasonably practical, and if you can't eliminate them, you'll minimise them as low as reasonably practical. Yet when it provides advice on how to do a formal safety assessment, it basically tells you to comply with the principles of ISO 31000 and to choose target levels of risk and safety and so forth, which is specifically against the will of all Australian parliaments.

This illustrates a mismatch between what senior decision makers and the boards worry about, which is the WHS legislation. These people understand their requirements and want to be compliant. But the tools and the processes that the engineers (and others) are using to do the day-to-day work in organisations, the Standards, is creating confusion.

Engineers should be looking at each credible critical (kill or maim) problem on a case-by-case basis and designing to ensure this has been eliminated so far as is reasonably practicable or if it can’t be eliminated, reduced so far as is reasonably practicable.

As from Paul Wentworth, a partner of MinterEllison says:

"Engineers should remember that in the eyes of the court, in the absence of any legislative or contractual requirement, an Australian Standard mounts only to an expert opinion about usual recommended practice. In the performance of any design, reliance on an Australian Standard does not relieve an engineer from a duty to exercise here's or her skill and expertise".

If you know that the legislation has the requirement to provide the highest level of protection as is reasonably practicable and you still choose to do work consistent with an Australian Standard, you are talking yourself into a very difficult place if it all goes wrong and you wind up in court. And you have expert witnesses like us acting against you.

When we brief legal counsel for organisations on the two different approaches (SFAIRP and target levels of risk and safety) prior to commencing any consulting work, they all agree that the target level of risk and safety approach encouraged by ISO 31000 does not meet the requirements of the WHS and OHS legislation. You cannot keep using target levels of risk and safety to make safety decisions. You can use it as a reporting tool, which is what the handbook says.

From the point of view of engineers, there are very many tools and techniques that can be used to help put a safety argument together and meet the requirements of the WHS legislation. R2A was a key contributor to the Engineers' Australia Safety Case Guidelines, which was signed off by the National Risk Engineering Society in 2016. The document was reviewed by a barrister to make sure that it was tight and consistent with the legislation.

Remember, it's not a Standard that's recognised good practice. It's the useful ideas in the Standards that are recognised good practice that you must consider.

The same applies to ISO 31000. It details a number of important points that are particularly useful, but the process encouraged acts against the fundamental purposes of WHS/OHS legislation.

Standards can provide some insight into particular issues of concern and some of the solutions available, but these shouldn’t doesn't stop us from thinking.

ALARP & the WHS Legislation

The recent surge in the ALARP debate amongst engineers has prompted the R2A partners to reconsider how it was that ALARP was developed at all and how it has caused so much controversy, at least in Australia. Our recent blogs Risk Paradigm Shift Takes a Generation and Is There a Difference between ALARP & SFAIRP? The Debate Continues covered much of this, but since the debate continues we felt it was worth a further comment.

The ALARP debate seems to have arisen from Sir Frank Layfield’s (a lawyer) Sizewell B Inquiry of 1987. Whilst he gave approval for the nuclear power station station to proceed, there were a number of matters that were unresolved including, for example, an understanding of the level of danger posed by anticipated radiation levels. Sir Frank recommended that this matter be investigated further.

Practically, the task was passed on to the then newly established (1975) UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE). Whilst Sir Frank was assisted by a large number of engineers, the UKHSE’s document, The Tolerability of Risk from Nuclear Power Stations (1988) appears to have been prepared mostly by scientists. It is a careful document. The so called dagger diagram which is used to describe the ALARP approach does not have any risk numbers shown on it. These are summarised in the appendix of the document.

Never-the-less, the use of numbers was popularly seized upon. That is, the risk numbers in the Appendix was applied to the diagram as shown above (from a summary by the International Atomic Energy Agency on the Tolerability of Risk the ALARP Philosophy.

This was all very unfortunate as it is a proposition the courts (at least Australian courts) were never able to accept. As Sir Harry Gibbs (Chief Justice of the Australian High Court) put it in 1982:

Where it is possible to guard against a foreseeable risk, which, though perhaps not great, nevertheless cannot be called remote or fanciful, by adopting a means, which involves little difficulty or expense, the failure to adopt such means will in general be negligent

(Turner v. South Australia (1982) 42 ALR 669).

That is, it does not matter how rare an event is, if the consequences are critical and more could have reasonably be done to prevent or manage the outcomes, then the courts, post-event, will consider this failure to be negligent.

Since this common law understanding is that which was put into the OHS/WHS legislation, the ALARP approach using target levels of risk became, by statute, quite unsupportable.

From the R2A perspective, this became clear when the OHS Act in Victoria (2004) commenced as the enabling legislation for major hazard facility (MHF) regulators. This result required that R2A change from being risk engineers to due diligence engineers. It also precluded R2A from providing MHF advice as long as relevant MHF regulators continued to use target-level-of-risk arguments rather than criticality driven safety-in-design arguments.

Happily, this changed in Victoria where the MHF regulator in 2022 moved to the Gibbs position. That is, the credible worst case outcomes (the science - which remains arguable for complex hazard scenarios) is described and then the possible control options considered (a design exercise), as shown in the diagram below.

From a pre-event perspective, the more scientists know, the better engineers can do, although there is a functional overlap between the two. Post-event, the courts are actually completing a retrospective design review to test if any design options were overlooked or poorly implemented from what is an awful, but now known, outcome.

This is entirely consistent with the thinking of David Howarth, the Professor of Law and Public Policy from Cambridge University (whom R2A sponsored to Melbourne in 2017) in his book Law as Engineering. The law is chiefly a design process, and the lawyers are looking to the engineers for inspiration (Watch this short presentation by David Howarth).

Based on this, there seems to be a general intellectual alignment emerging amongst lawyers, engineers and scientists on how this all should be done.

If you’d like to discuss further how our work helps ensure governance outcomes that meet Australian WHS/OHS legislation that all reasonably practicable precautions are in place for high consequence, low likelihood events, head to our contact page.

Risk paradigm shifts take a generation

R2A recently acted as expert witnesses before VCAT (The Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal) regarding the rejection of a planning permit for a two dwelling redevelopment on a single site.

The planning permit had been rejected by the relevant council on the basis of advice from WorkSafe Victoria that population ‘densification’ within a 1 kilometre ‘outer safety area’ distance of the boundary of a major hazard facility (MHF) was undesirable (see https://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/land-use-planning-near-major-hazard-facility).

As the particular matter is presently sub judice, we won’t be commenting on specific details of this case in question at this time. But we observe that because the new MHF land use guidelines only came out mid 2022, it has created an avalanche of cases before VCAT with different VCAT members using different approaches to accept or reject development proposals which has flow on implications including appeals to the Supreme Court.

However, most interestingly, from a professional practice viewpoint, we can now confirm that the Victorian Major Hazard Regulator has adopted a consequence based approach to land use planning overturning the long established risk based (QRA - quantified risk assessment) approach.

This is something R2A has pushed for years. Indeed, we stopped being risk engineers and became due diligence engineers in the late 2000’s and generally stopped doing MHF safety case work because of this concern. That is, that QRA was indefensible in general and particularly for land use safety planning. Such planning should be consequence based, testing for effective risk controls for predicted credible event severity as shown in the diagram below.

The reason is simple, as the 2004 Maxwell Review which resulted in the 2004 OHS Act (the enabling legislation for MHFs) in Victoria suggests, that everyone is entitled to an equal level of protection. A hazard cannot be discounted merely because it is considered rare. It does not matter how low the risk is, if more can reasonably be done, then it should be and the failure to do so will be negligent (paraphrasing Chief Justice Sir Harry Gibbs in Turner v. The State of South Australia (1982)).

For example, the fact that the likelihood of a single fatality is less than say 1 x 10-7 per year does not mean it can’t happen and nothing further needs to be done. As Section 4 of the Vic OHS Act notes: The importance of health and safety requires that employees, other persons at work and members of the public be given the highest level of protection against risks to their health and safety that is reasonably practicable in the circumstances.

Or in the words of Barry Sherriff (one of the lawyers who helped draft the WHS legislation): Simply makes it clear that you start with what can be done and only do less when where it reasonable to do so.

This means that in R2A’s view, safety-in-design solutions to eliminate or prevent hazard consequences associated with MHFs should be considered and tested for reasonableness as part of the planning/building permitting process.

Look out for Season 2 of Risk! Engineers Talk Governance podcast where Richard & Gaye discuss this further.

Is there a difference between ALARP & SFAIRP? The debate continues.

We recently discovered a Linkedin post and comment trail where an old R2A ‘ALARP versus SFAIRP’ image was used. Some extra words had been inserted on it by others emphasising the two terms - adding confusion. There were a lot of varying comments in the thread debating if there’s a difference between ALARP & SFAIRP, but rather than go through them individually, we have chosen to summarise R2A’s take on where this is at:

Risk assessment (especially QRA - quantified risk assessment) using technical risk targets is now and always has been flawed as it can prevent consideration of possible further controls due to the perceived lowness of the risk.

Often when looking at a corporate risk register, the last items on the list are the critical ones in consequence terms but placed at the bottom in risk terms because of their perceived rareness.

Discounting consequences (and thereby possible controls) by the unlikeliness of the event has always been in error. The MHF regulator in Victoria corrected this last year (read Risk Paradigm Shifts Take a Generation) releasing a pent-up Kraken of land use planning pain.ALARP and SFAIRP are not terms created by R2A. They come from the UK.

ALARP was created by the Health and Safety Executive. We think it was an unfortunate and unnecessary development. It encouraged the use of risk targets, thereby inhibiting consideration of possible further practicable controls. Just do a search for ALARP in Google and dagger diagrams with risk targets abound. It may not be what was intended but that is what it encouraged. It flowed into dam safety, maritime and aviation safety and many other areas.

SFAIRP appears to have been created to contrast the difficulties with ALARP. For example: Felix Redmill from Newcastle University (UK) observed in 2010:

What confidence can there be that a risk deemed ALARP would also be judged to have been reduced SFAIRP? Can the two concepts be said to be identical? They cannot. As already pointed out, they were defined by different parties (the law-makers and the safety regulator) for different purposes (stating a legal requirement and offering guidance on a strategic approach to meeting it). But does one imply the other? No.

There can be no guarantee that the same ALARP decision would be arrived at by two different practitioners, and certainly none that an ALARP decision arrived at now in an industrial context would, later be judged by non-engineers in a legal context to have met the SFAIRP test.The UK HSE’s document, ALARP “at a glance” equates the two concepts. But later in the same document notes:

You may come across it as SFAIRP (“so far as is reasonably practicable”) or ALARP (“as low as reasonably practicable”). SFAIRP is the term most often used in the Health and Safety at Work Act and in Regulations. ALARP is the term used by risk specialists, and duty-holders are more likely to know it. We use ALARP in this guidance. In HSE’s view, the two terms are interchangeable except if you are drafting formal legal documents when you must use the correct legal phrase.In R2A’s view, it has always been about ensuring that all reasonably practicable precautions are in place.

You should strenuously avoid any ‘risk assessment’ process that may prematurely exclude viable potential controls from further consideration. And the prudent approach is to always use the correct legal term in the way legislation and the courts apply it, irrespective of what a regulator says to the contrary. Why create confusion by having two terms?

Also read: SFAIRP Not Equivalent to ALARP

Demonstrating SFAIRP (Conference Paper, CORE 2023)

This paper was presented by at CORE (Conference on Railway Excellence) June 2023 in Melbourne Australia by Gaye Francis BE MAICD FIEAust, Managing Partner of R2A.

SUMMARY

SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable) is the ‘modern’ definition of ‘safe’. Shrouded in the legal concept of the ‘safety case’, it is actually the legislated implementation of the judicial form of the principle of reciprocity – the golden rule – do unto others, incorporated into the common law by the Brisbane born English law lord, Lord Atkin in 1932. [1]

In rail safety terms, it asks the question; “If you are affected in any way by a rail network (passenger, driver at a level crossing, rail worker etc), how would you expect the network and rolling stock to be designed and managed in order for it to be considered safe?”

The answer is that it now requires a public demonstration that all reasonably practicable precautions are in place in a way that satisfies the will of our parliaments and our sovereign’s courts, otherwise known as a SFAIRP safety case.

1 INTRODUCTION

The rise of Work Health and Safety [2] (WHS) legislation and associated Rail Safety National Law [3] (RSNL) mandates that there needs to be a positive demonstration of safety due diligence. If there is a conflict between the two Acts, the WHS legislation takes precedence (section 48 of RSNL). Presently, the most robust and effective way to achieve this known to the authors is by the use of the safety case concept to demonstrate SFAIRP (that hazards, risks and harm have been eliminated or reduced so far as is reasonably practicable), that is, the rise of the SFAIRP safety case.

Safety Cases have been around for a long time. In Victoria they are de rigueur in rail, gas, petroleum, power and major hazards industries. For example, the Victorian Major Hazard regulations [4] (OH&S, 2000) have required that the operator must identify all hazards that could cause major incidents (Section 302) and that such a safety case must be signed off by the most senior company officer resident in Victoria (Section 402).

The inclusion of criminal manslaughter provisions in safety legislation (which therefore includes dealing with hazards that were either known or ought to have been known) has reinforced this. It is now absolutely essential for anyone (especially officers as defined by corporations’ law) responsible for the design, construction and management of any facility that can cause fatalities, like railways, to positively demonstrate safety due diligence in a way that is scientifically defensible, organisationally useful, publicly digestible and which will survive post-event legal scrutiny.

Note also that on 1 July 2021, Victoria commenced the SFARP provisions of the Environmental Protection Act 2017 [5]. Amongst other things, this Act imposes a general environmental duty (GED) on a person to minimise, as far as reasonably practicable (SFARP), risks or harm to human health and the environment (Section 25). Particularly, it further requires the person to eliminate such risks, and if not reasonably practicable to do so, to reduce them so far as reasonably practicable (Section 6). If not already, it appears to be only a matter of time before the SFA(I)RP concept will be entrenched in other legislation and regulatory instruments.

In this context, it is important to remember that legally, safety risk does not arise because something is inherently dangerous, which railways potentially are, rather it arises because there are insufficient, inadequate or failed precautions as determined by our courts, post event.

2 The Safety Case Concept

The safety case concept is a well-established method for organisationally demonstrating safety due diligence. As the English law lord, Lord Cullen put it in 2001 [6]:

A safety case regime provides a comprehensive framework within which the duty holder’s arrangements and procedures for the management of safety can be demonstrated and exercised in a consistent manner. In broad terms the safety case is a document – meant to be kept up to date – in which the operator sets out its approach to safety and the safety management system which it undertakes to apply. It is, on the one hand, a tool for internal use in the management of safety and, on the other hand, a point of reference in the scrutiny by an external body of the adequacy of that management system – a scrutiny which is considered to be necessary for maintaining confidence on the part of the public.

Safety cases have parallels with business cases. The latter are usually drawn up to convince a financier that an organisation is viable. The object is to assure that all significant factors affecting the organisation have been identified and that appropriate measures are in place to maximise the positive factors and minimise the negative ones. This is usually the responsibility of the highest levels of management of the organisation.

3 Demonstrating SFAIRP

This section outlines R2A’s Y Model [7] developed in 2011 to specifically address the requirements of the model WHS Act, which in turn satisfies the obligations of the RSNL. That is, to eliminate risks to health and safety so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP), and if it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate risks to health and safety, to reduce those risks so far as is reasonably practicable. The process has been applied to very many organisations since, always to the satisfaction of relevant legal counsel.

Figure 1. R2A ‘Y’ Model

The safety due diligence approach implements the ‘Y’ model shown above based on a diagram after Sappideen and Stillman, 1995 [8]. This has four steps summarised below.

3.1 Credible critical issues completeness

This is a completeness check to ensure all credible critical safety issues have been identified. That is, the issues faced by a rail operator that have the potential to cause serious harm. This can be done in a number of ways such as vulnerability or consequence assessments (who is exposed to what hazards), past incidents and generative interviews with recognised experts and so on.

Figure 2. Applies to Critical Threats and Hazards

3.2 Identifying all possible practicable precautions

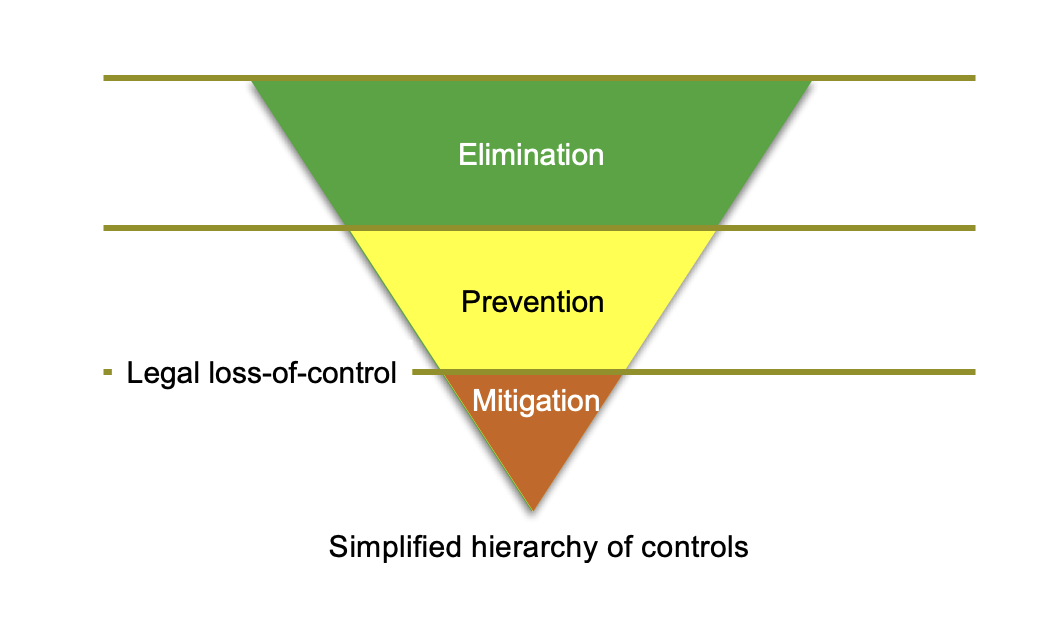

The second step is to develop a process that ensures all physically possible measures to eliminate or minimise the risk have been consistently considered. Part of this will include testing for controls and safety measures identified by rail owners and operators. Legislation and regulation require that risk control must be based upon the Hierarchy of Controls as shown below and in the order of most to least preferred, elimination, prevention and mitigation. These decisions need to be adequately documented with appropriate sign off.

Figure 3. Hierarchy of controls as tested in court post-event

3.3 Reasonableness & barrier implementation

This step looks at all of the precautionary options that are possible and available; and in view of what is already in place decides on additional precautionary effort. The decision is a balancing exercise and involves taking into account and weighing up all relevant matters including, on the one hand:

the likelihood of the hazard or risk concerned occurring;

the degree of harm that might result from the hazard or risk;

what the person knows, or should reasonably know, about the hazard or risk and ways of eliminating or minimising that risk;

the availability and suitability of ways to eliminate risk; and also costs associated with available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, including whether the cost is grossly disproportionate to the risk.

Or, put another way, the decision is based on the balance of the significance of the risk (likelihood and consequence) versus the effort required to reduce it. Effort includes cost (how much), the degree of difficulty and inconvenience (how hard it is to implement) and utility of conduct (what other things go missing if that course of action is adopted). In this context, recognised good practice is the starting point, not the goal. This is where disproportionality comes into play.

Disproportionality results from the law of diminishing returns (the pain is not worth the gain) for precautionary effort.

For example, if the first precaution reduces the risk by 99%, the next precaution can only affect the remaining 1% and so on. So, in terms of the balance of the significance of the risk vs the effort required to reduce it, the scales thump to the ‘let’s not do anymore for now’ side very quickly for effective precautions.

3.4 Quality assurance

Quality process to confirm that agreed precautions are sustained.

4 Possible Safety Case Arguments

Efforts to demonstrate how risk should best be managed have given rise to a number of risk management decision paradigms all of which have or are being used to support safety case arguments in different industries. A paradigm is a universally recognised knowledge system that for a time provides model problems and solutions to a community of practitioners (Kuhn, 1970) [9]. New paradigms based on more comprehensive or convincing theories may supersede older ones or exist co-jointly with them.

This section describes a number of the most common risk paradigms [10] and details some of the advantages and disadvantages of each. They are listed in the order in which they became historically apparent. The paradigms are:

i. The rule of law.

ii. Traditional risk management historically typified by Lloyds Insurance and the US Factory Mutuals’ highly protected risk (HPR) approaches.

iii. Asset based risk management, typified by engineering-based failure modes, effects and criticality analysis (FMECA), hazard and operability (Hazop) and quantitative risk assessment (QRA) approaches.

iv. Threat-based risk management typified by strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) and vulnerability type 'top-down' mission-based military appreciation type analyses.

v. Solution-based ‘good practice’ risk management rather than hazard-based risk management.

vi. Biological, systemic mutual feedback loop processes, often manifested in hyper-reality computer-based simulations.

vii. Risk culture concepts including quality type approaches.

4.1 The rule of law

The power of the legal approach is that it is time-tested and proven. The Brisbane born English law lord, Lord Atkin unleashed an avalanche of negligence claims in the common law world (Donoghue v Stevenson 1932) [1] with the view that:

You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour.

If the judiciary is independent of political and commercial interests of the day, then an independent and potentially fair resolution can occur. Perhaps this is why it works; both the political and judicial systems must simultaneously fail before social breakdown occurs and there is potential for catastrophic social dislocation. The weakness of the legal approach, certainly in an adversarial legal system like ours, is that the courts remain courts of law rather than courts of justice. As The Institution of Engineers, Australia (1990) notes [11]:

Adversarial courts are not about the dispensing of justice, they are about winning actions. In this context, the advocates are not concerned with presenting the court with all the information that might be relevant to the case. Quite the reverse, each seeks to exclude information considered to be unhelpful to their side's position. The idea is that the truth lies somewhere between the competing positions of the advocates.

Further, courts do not deal in facts; they deal in opinions.

What is a fact? Is it what actually happened between Sensible and Smart? Most emphatically not. At best, it is only what the trial court, the trial judge or jury - thinks happened. What the trial court thinks happened may, however, be hopelessly incorrect. But that does not matter - legally speaking.

4.2 Insurance and historical records

The Lloyds Insurance and the Factory Mutual Highly Protected Risk (HPR) [12] approaches historically typify insurance-history based risk management. Looking at past incidents and losses and comparing these to existing plants and facilities allows judgements to be made about (future) risk. The difference historically is that one approach, Lloyds', has a financial focus, whereas the Factory Mutuals’ focus is targeted at a level of engineered and management excellence.

The power of the insurance process is the very tangible nature of history, and in a sense the results represent the ultimate Darwinian ‘what if’ analysis. Its weakness is that in the modern rapidly changing world, empirical history has become an increasingly less certain method of predicting the future.

4.3 Asset and hazard

Asset based risk management is typified by engineering based FMECA (failure modes effects and criticality analysis), Hazop (hazard & operability) and QRA (quantitative risk assessment) event-based approaches. The power of event-based techniques lies in the detailed scrutiny of complex systems and the provision of closely-coupled solutions to identified problems. It revolves around hazards and assets component failure events and resulting flow-on steps throughout the asset (rail) seeing if it culminates into partial or full failure of the asset (rail) & its system function. Any proposed risk control solutions can be both focussed and specific. They can be easily considered for cost/benefit results. Each step (effectively a potential barrier) can be assessed for SFAIRP. The resulting risk registers are powerful decision-making tools.

However, these methods have to separately address common cause or common mode failures which became apparent from major loss events that the authors have investigated. Event-based techniques typically do not examine how a catastrophic failure elsewhere might affect a particular component or the others around it. In the case of FMECA and QRA, after assessing failure modes, care has to be taken in determining what failure modes are mutually exclusive and what needs common cause / mode consideration / adjustment and how this translates to risk control solutions.

4.4 Threat (error) and vulnerability - military intelligence

Threat-based risk management is typified by SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) and vulnerability type top-down analyses. These methods mostly identify areas of general strategic concern rather than solutions to particular problems. Its strength is that is provides a completeness argument for why no credible critical issues have been overlooked. In rail safety cases, it is a particularly common approach to assess the impacts of rail events like derailment, collision etc on the critical exposed groups.

4.5 Recognised good practice

An alternative to this is a precautionary (solution) based good practice risk management. The good practice risk management approach simply looks at all the good ideas other people in an industry use to see if there is any reason why such ideas ought not to be applied at one’s own site. The good practice approach is particularly powerful in a common law due diligence sense. If there were a simple solution to a serious problem implemented at a competitor's facility, then common law negligence could arise if failure to adopt this good practice resulted in something going badly wrong at the subject site.

A good practice process is one of the few approaches that address this difficulty. In a sense, this is confirming the view that liability arises when there are unimplemented good ideas rather than the existence of hazards or vulnerabilities in themselves. For example, could a marine pilot’s PPU (personal pilotage unit) be adapted and used for situational awareness by a train driver for long distance travel between states?

4.6 Evolutionary simulation

Biological/computer simulation paradigms are derived from the application of evolutionary concepts developed in virtual reality. This amounts to modelling a complex system in a virtual reality environment and playing endless what if scenarios. Such computer simulations can be most easily used for worst-case combinations of variables. The simulations can also be fine-tuned by calibrating against empirical data or through carefully controlled physical experiments.

4.7 Culture

James Reason [13], a psychologist, develops a cultural paradigm model in several ways (Reason, 1997). He notes three types of risk culture:

Pathological - don’t want to know and messengers arriving with bad news are ‘shot’

Bureaucratic- messengers are listened to if they arrive alive

Generative - actively seek bad news and train and reward messengers

Figure 4. SFAIRP and Reason’s paradigms

The importance of these concepts is well known in rail safety.

These paradigms are listed in Table 1 below, together with the three generic techniques by which humans seem to make decisions. These are:

Expert reviews. The difficulty with this approach is that, if you don’t think the expert is right, there needs to be at least two alternative experts to change the decision.

Facilitated workshops. This parallels the adversarial legal system, where the sovereign’s champions (usually two barristers) present the alternative cases and the judge or jury decides.

Selective interviews, which parallels the inquisitorial system where someone armed with vast powers subpoenas persons until they have enough evidence to come to a judgement. In the Australian and New Zealand systems, this is represented by Coronial Enquiries and Royal Commissions.

Table 1 Available techniques

Each of these paradigms and decision techniques has different pros and cons depending on the culture of the organisation and the nature of a particular task. The best methodologies that might be used in the implementation of a safety case in each of the risk paradigms as determined by the Risk Engineering Society of Engineers Australia (2014) [10] are highlighted in Table 1.

5 Exemplar SFAIRP safety case

This section considers which of the possible safety case arguments would support the SFAIRP process as applied to rail safety cases. It is difficult to prescribe which arguments are optimal without a particular railway in mind. There is no single ‘right way’ to complete a SFAIRP safety case. The arguments that are to be used to support the safety case need to be established in advance and are likely to depend on the circumstances of each rail and are unlikely to be the same for any two railways. For example, the safety argument for a suburban electric network is likely to be entirely different to an outback mining corridor or an isolated, single train heritage track.

5.1 Credible critical issues completeness argument

For the particular rail under consideration, what are the best approaches to determine which are the credible critical failure mechanisms for that particular railway?

5.2 Identifying all possible practicable precautions

There are a number of generic analysis tools that can be employed to identify possible practicable precautions and then facilitate the reasonableness assessment of same. They include cause-consequence diagrams, threat-barrier (bow-tie), layers of protection (LPOA) and Venn (Swiss Cheese) diagrams. These are discussed in Robinson & Francis (2022) [14]. However, in the experience of the authors as expert witnesses, the one that has proven to be most successful with the courts and the public has been single line threat-barrier diagrams.

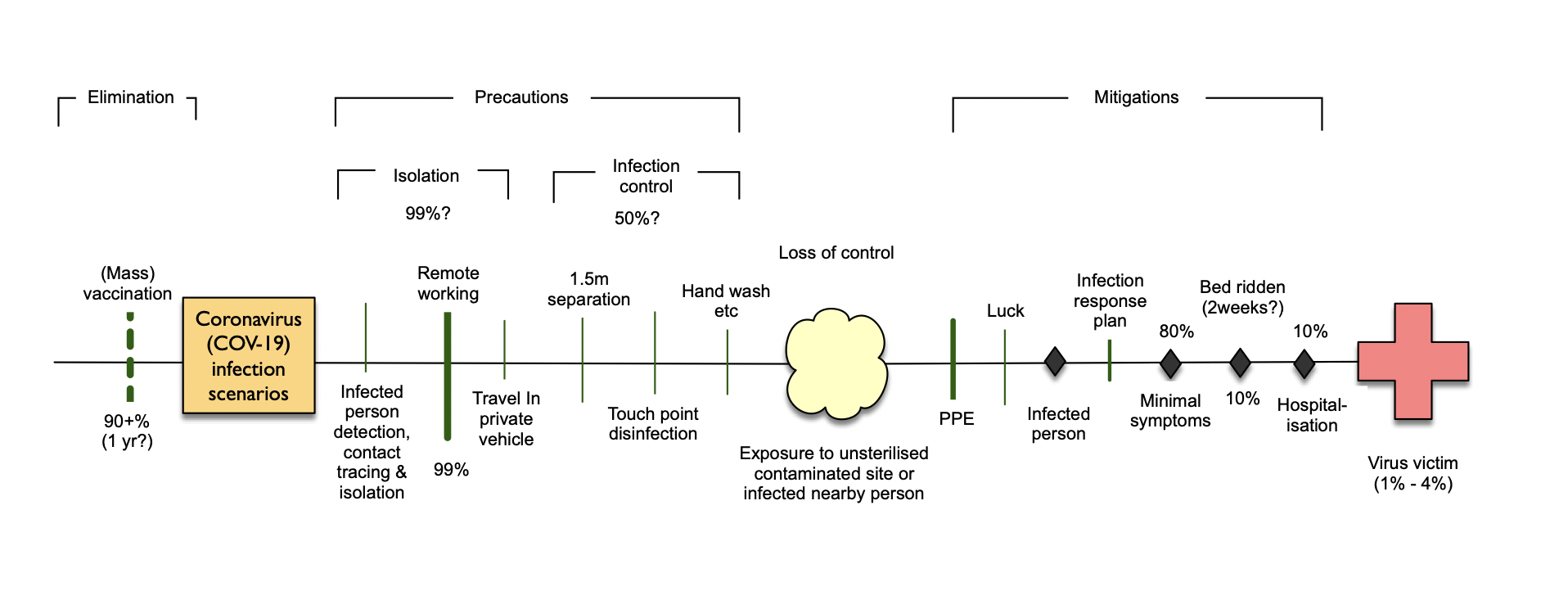

The following sample threat barrier diagram has been developed for a representative credible critical issue associated with railways. It identifies the legal loss-of-control point and the existing and possible control barriers. The legal loss-of-control point is the point at which the laws of nature and man align. Controls that act before the loss-of-control point are legally precautions that stop the loss-of-control from occurring (that is, reduce the likelihood of its occurrence) whilst controls that act after the loss-of-control point are mitigations and reduce the scale of the consequences. Effectively, such a diagram describes the legislatively mandated hierarchy-of-control moving from left to right.

Figure 5. Sample single line threat-barrier diagram

The key is not only to identify the existing barriers (shown as solid vertical lines) but to also identify all further possible practical controls (shown as dotted vertical lines) including emerging technology and what is considered recognised good practice especially in new rail projects. For example, new rail tunnel ventilation and smoke extraction systems are typically designed to handle a fully developed worst case train fire with concomitant evacuation paths which, essentially smoke blown one way with evacuating people moving in the other direction. This is a good practice precaution that should then be tested for reasonableness for any upgrade works on existing rail tunnels.

Another example, could a Driver’s Resource Management (DRM) system modelled on the marine pilots PPU (personal pilotage unit) and BRM (Bridge Resource Management) be provided on interstate trains? The technology is well established, sold globally and would have only to be adapted.

Preliminary discussions with manufacturers [15] at the AMPI conference [16] in Hobart in March this year suggest that the hardware cost per driver would be around $5,000. This would provide a completely independent battery power (15 hours), weather resistant driver management system (DMS) including a driver’s iPad with magnetically attached GNSS (GPS, Glonass, Galileo, Qzss, Beidou etc) positioning units (with SBAS correction to 1m accuracy) at either end of a train (to confirm train continuity), each with G3, G4, and G5 real time communications and satellite data connections (including jamming and spoofing resistance). Such units would automatically provide for voice recording of the driver and train control.

Figure 6 Marine pilot PPU [17]

The main cost would be interfacing the track data and real-time environmental databases and train movement information provisionally estimated at $50m for the whole of Australia. Coupled with TMACS [18] train control (originally functionally certified by R2A for NSW in the late 90s) and watchdog monitoring this would probably increase driver, track gang and train controller situational awareness by up to 2 orders of magnitude.

That is to say, it is not enough to only consider your own industry for new precautions to address known risks.

5.3 Reasonableness and barrier Implementation

In determining reasonableness, further controls must be considered in hierarchy of control order based on the balance of the significance of the risk verses the effort required to reduce it. Some organisations look at short, medium and long term SFAIRP options. For example, upgraded train protection system on a section of track may be the ultimate long term (5-10 year) SFAIRP option but a shorter term (12 months) SFAIRP option may be to reduce the number of possible train collision interactions, enhance signal sighting for drivers and optimise the performance of the existing mechanical train stops.

From a due diligence perspective, not only is it important to document further controls to be implemented but also record why certain controls are not considered reasonable. Also, it is important that:

Recognised good practice such as represented in a standard is just the starting point. Further good ideas are to be tested for value. For example, the option to piggy back on ADS-B [19] from the aviation industry thereby treating trains as low flying aircraft is an intriguing idea.

Decisions should be made to a common law standard consistent with decisions of the High Court of Australia, such as Justice Mason’s decision in Wyong Shire Council v Shirt (High Court of Australia, 1980) [20].

Precautions with less than a 50% chance of working (as a likelihood assessment) ought not to be considered / adopted as (legally) they are more likely to fail than succeed.

Consultation with those who are at risk is legislatively mandated. For major community issues, this consultation is expected to be wider than just teams of experts described in the workshop sign-off below.

5.4 Quality assurance

5.4.1 Workshop sign-off

One point often overlooked in most SFAIRP (risk) workshops is the sign-off. Workshops should be organised to ensure that the best available knowledge and expertise is in the room. This means however, that at the end of the workshop session, the group should be formally tested to see if there are any other issues of concern which had not been raised or adequately addressed during the workshop session, and, more importantly, if there were any other good ideas or precautions that should be put on the table for consideration. Any issues raised should be tested and resolved formally.

5.4.2 Review by legal counsel

Most legal advice regarding the demonstration of due diligence as required by the model WHS legislation is focussed on a compliance audit to the relevant section and clauses. But this should be the outcome of the due diligence process, not the cause. That is, in order to be safe in reality, it is firstly necessary to manage the laws of nature. Confirming that this has been achieved to the satisfaction of the laws of man is a secondary exercise and one to which lawyers can be usefully and efficiently tasked, especially regarding consensus as to the legal loss-of-control point/s. If it isn’t clear to the lawyers on reading the safety case that the legal loss-of-control point is sound, then the application of the hierarchy of controls is likely to be confused and leave everyone and everything open to post-event legal argument and potential liability.

5.4.3 Articulated enduring QA process

The procedures by which agreed precautions are to be sustained into the future needs to be articulated and adequately documented.

6 Conclusion

The SFAIRP safety case is increasingly being entrenched in legal systems and regulatory instruments.

Our parliaments and courts are not requiring that ‘you get it right’ all the time, which is a logical impossibility of the human condition. What the WHS/OHS/RSNL/EPA legislation demands is a continuous, positive demonstration of safety due diligence. What the community and courts get ‘cranky’ about, post event, is when a precaution exists which was either known or ought to have been known, which was reasonable in all the circumstances and which, if it had been in place would have stopped the horror from occurring.

This means that an essential aspect of a SFAIRP safety case is that there is a continual testing for new or enhanced risk control ideas, to see if they have value and ought to be implemented. But this has to be achieved in a way which satisfies legal scrutiny, pre and post event.

This also means that it is difficult to see how any safety case for any rail operator can be considered robust unless it has been reviewed by relevant legal counsel. In a very real sense, pre-event verification of a safety case can make lawyers really, really useful to accredited rail operators.

References

1. United Kingdom House of Lords (1932). Donoghue v Stevenson. UKHL 100 1932.

2. Work Australia (2011). Model Work Health and Safety Bill. 23 June 2011.

3. The Rail Safety National Law was passed through the South Australian Parliament on 1 May 2012 replacing 46 pieces of State, Territory and Commonwealth legislation.

4. Occupational Health and Safety (Major Hazard Facilities) Regulations 2000 S.R. No. 50/2000 (Victoria).

5. Environment Protection Act 2017(Victoria). Authorised Version incorporating amendments as at 1 July 2021.

6. Cullen Rt Hon Lord (2001). Transport, regulation and safety: a lawyer’s perspective. The Transport Research Institute, United Kingdom.

7. Francis, Gaye and Richard M Robinson, and (2021). Criminal Manslaughter and How not to do it. (Reprinted 2023). R2A Pty Ltd. Melbourne.

8. Sappideen, Carolyn and R H Stillman (1995). Liability for electrical accidents: risk, negligence and tort. Engineers Australia Pty Limited, Crow’s Nest, Sydney. Page 22.

9. Kuhn T S (1970). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 2nd ed. Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

10. Engineers Australia, Risk Engineering Society (2014). Safety Case Guideline. Third edition.

11. The Institution of Engineers, Australia (1990). Are you at risk?

12. FM Global. See: https://www.fmglobal.com.au/about-us/our-business/our-history viewed 3rd March 2023.

13. Reason, James (1997). Managing the Risks of Organisational Accidents. Ashgate Publishing Limited. Aldershot, UK.

14. Robinson, Richard M and Gaye Francis (2022). Engineering Due Diligence (12th edition, reprinted 2023). R2A Pty Ltd. Melbourne.

15. Navicom Dynamics Ltd (New Zealand) and AD Navigation AS (Norway).

16. Australasian Marine Pilots Institute. 2023 Hobart. Building Resilient Pilotage Conference.

17. Navicom Dynamics Ltd. See: https://navicomdynamics.com/en/products/channelpilot viewed 3rd March 2023.

18. 4Tel Pty Ltd. See: https://4tel.com.au/index.php/en/news/12-products/network-control-systems/22-4eta-train-authorities.html%20viewed%203rd%20March%202023. Viewed 3rd March 2023.

19. Air Services Australia. See: https://www.airservicesaustralia.com/about-us/projects/ads-b/how-ads-b-works/ viewed 3rd March 2023.

20. High Court of Australia (1980). Wyong Shire Council vs Shirt. HCA 146 CLR 40.

Why SFAIRP is not a safety risk assessment

Weaning boards off the term risk assessment is difficult.

Even using the term implies that there must be some minimum level of ‘acceptable safety’.

And in one sense, that’s probably the case once the legal idea of ‘prohibitively dangerous’ is invoked.

But that’s a pathological position to take if the only reason why you’re not going to do something is because if it did happen criminal manslaughter proceedings are a likely prospect.

SFAIRP (so far is as reasonably practicable) is fundamentally a design review. It’s about the process.

The meaning is in the method, the results are only consequences.

In principle, nothing is dangerous if sufficient precautions are in place.

Flying in jet aircraft, when it goes badly, has terrible consequences. But with sufficient precautions, it is fine, even though the potential to go badly is always present. But no one would fly if the go, no-go decision was on the edge of the legal concept of ‘prohibitively dangerous’.

We try to do better than that. In fact, we try to achieve the highest level of safety that is reasonably practicable. This is the SFAIRP position. And designers do it because it has always been the sensible and right thing to do.

The fact that it has also been endorsed by our parliaments to make those who are not immediately involved in the design process, but who receive (financial) rewards from the outcomes, accountable for preventing or failing to let the design process be diligent is not the point.

How do you make sure the highest reasonable level of protection is in place? The answer is you conduct a design review using optimal processes which will provide for optimal outcomes.

For example, functional safety assessment using the principle of reciprocity (Boeing should have told pilots about the MCAS in the 737 MAX) supported by the common law hierarchy of control (elimination, prevention and mitigation). And you transparently demonstrate this to all those who want to know via a safety case in the same way a business case is put to investors.

But the one thing SFAIRP isn’t, is a safety risk assessment. Therein lies the perdition.

Does Safety & Risk Management need to be Complicated?

With Engineer’s Australia recent call-out on socials for "I Am An Engineer" stories, I was discussing career accomplishments with a team member (non-Engineer) and we were struck by how risk and safety need not be complicated – that the business of risk and safety, especially in assessment terms has been over-complicated.

Two such career accomplishments that really brought this home was my due diligence engineering work on:

- Gateway Bridge in Brisbane

Our recommendation was rather than implement a complicated IT information system on the bridge for traffic hazards associated with wind, to install a windsock or flag and let the wind literally show its strength and direction in real time. A simple but effective control that ensures no misinformation. - Victorian Regional Rail Level Crossings

R2A assessed every rail level crossing in the four regional fast rail corridors in Victoria for the requirements to operate faster running trains. The simple conclusion, that I know saved countless lives, was to recommend closing level crossings where possible or provide active crossings (bells and flashing lights) rather than passive level crossings.

However, some risk and safety issues are not as simple, like women’s PPE.

The simple solution, to date, has been for women to wear downsized men’s PPE and workwear. But we know this is not the safest solution because women’s body shapes are completely different to men.

My work with Apto PPE has been about designing workwear from a due diligence engineering perspective. This amounted to the need to design from a clean slate (pattern, should I say!) -- designing for women’s body shapes from the outset and not tweaking men's designs.

Not everyone does this in the workwear sector, but as an engineer, I understand the importance of solving problems effectively and So Far As Is Reasonably Practicable (SFAIRP).

By applying the SFAIRP principle, you are really asking the question, if I was in the same position, how would I expect to be treated and what controls would I expect to be in place, which is usually not a complicated question.

And, maybe, my biggest career accomplishment will be the legacy work with R2A and Apto PPE in making a difference to how people think about and conduct safety and due diligence in society.

Find out more about Apto PPE, head to aptoppe.com.au

To speak with Gaye about due diligence and/or Apto PPE, head to the contact page.

Simplifying Hierarchy of Control for Due Diligence

The hierarchy of control is one of those central ideas that safety regulators have been using forever. But it is also one of those very simple ideas that has caused enormous confusion in due diligence.

In hierarchical control terms, the WHS legislation (or OHS in Victoria) provides for two levels of risk control: elimination so far as is reasonably practicable (SFAIRP), and if this cannot be achieved, minimisation SFAIRP.

In addition, criminal manslaughter provisions have been enacted in many jurisdictions.

The post-event test for this will be the common law test albeit to the statutory beyond reasonable doubt criteria.

For example, from WorkSafe Victoria:

The test is based on the existing common law test for criminal negligence in Victoria, and is an appropriately high standard considering the significant penalties for the new offence.

https://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/victorias-new-workplace-manslaughter-offences

Post-event in court, from R2A’s experience acting as expert witnesses, there are three levels in the hierarchy of control:

- Elimination,

- Prevention, and

- Mitigation.

In causation terms most simply shown as single line threat-barrier diagrams such as the one for Covid 19 below.

Our collective safety regulators have other views. For example, the 2015 Code of Practice (How to Manage Work Health and Safety Risks) which has been adopted by ComCare and NSW has 3 levels of control measures whereas many other jurisdictions adopt the 6-level system like Western Australia. Victoria has a 4-level system.

This inconsistency between jurisdictions seriously undermines the whole idea of harmonised safety legislation. And it also muddles optimal SFAIRP control outcomes. For example, engineering can be an elimination option, as in removing a navigation hazard, a preventative control as in machine guarding, or a mitigation as in an airbag in a car.

In R2A’s view, which we have tested with very many lawyers, the judicial formulation shown below is the only hierarchy of control capable of surviving legal scrutiny and R2A’s preferred approach.

Contact the team at R2A Due Diligence for further advice on hierarchy of controls for due diligence.

SFAIRP Culture

The Work Health & Safety (WHS) legislation has changed the way organisations are required to manage safety issues. With the commencement of the legislation in WA on 31 March 2022, as well as the introduction of criminal manslaughter provisions in some states, there appears to be an increased energy around safety due diligence.

The legislation requires SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable).

A duty imposed on a person to ensure health and safety requires the person:

(a) to eliminate risks to health and safety, so far as is reasonably practicable; and

(b) if it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate risks to health and safety, to minimise those risks so far as is reasonably practicable.

This means that the historical concepts of ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable), risk tolerability and risk acceptance do not apply.

From the handbook for the Risk Management Standard (ISO 31000):

Importantly, contemporary WHS legislation does not prescribe an ‘acceptable’ or ‘tolerable’ level of risk—the emphasis is on the effectiveness of controls, not estimated risk levels. It may be useful to estimate a risk level for purposes such as communicating which risks are the most significant or prioritising risks within a risk treatment plan. In any case, care should be taken to avoid targeting risk levels that may prevent further risk minimisation efforts that are reasonably practicable to implement.

(SA/SNZ HB 205:2017 page 14)

In cultural terms, James Reasons outlines three types of risk culture: pathological, bureaucratic and generative.

The SFAIRP approach is attempting to move safety from the pathological question: Is this bad enough that we have to do something about it, to the generative perspective: Here’s a good idea, why wouldn’t we do it?

In this framework, Codes of Practice and Standards are the bureaucratic starting point. The objective is to do better than that, when reasonably practicable to do so. The aim is the highest reasonable level of protection.

The Act ensures a ‘transparent bias’ in favour of safety. As the model act says (and all jurisdictions including NZ have adopted):

… regard must be had to the principle that workers and other persons should be given the highest level of protection against harm to their health, safety and welfare from hazards and risks arising from work as is reasonably practicable.

This is a change in mindset for many organisations, but one which easily aligns with human nature.

On a personal level, we (at R2A) are always trying to do the best we can especially for others. This is one of the reasons I continue to work on Apto PPE, a line of fit-for-purpose female hi vis workwear including a maternity range.

I know that females only represent a small proportion of the engineering and construction section (around 10%), but the question shouldn’t be “is the current options of PPE for women bad enough that we need to do something about it?”

The question should be: Can we do better than scaled down men’s PPE? And Apto PPE is happy to provide an option for organisations that want to do better.

SFAIRP not equivalent to ALARP

The idea that SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable) is not equivalent to ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) was discussed in Richard Robinson’s article in the January 2014 edition of Engineers Australia Magazine generates commentary to the effect that major organisations like Standards Australia, NOPSEMA and the UK Health & Safety Executive say that it is. The following review considers each briefly. This is an extract from the 2014 update of the R2A Text (Section 15.3).

The idea that SFAIRP (so far as is reasonably practicable) is not equivalent to ALARP (as low as reasonably practicable) was originally discussed in Richard Robinson’s article in the January 2014 edition of Engineers Australia Magazine. At the time, it generated much commentary to the effect that major organisations like Standards Australia, NOPSEMA and the UK Health & Safety Executive say that it is.

Fast forward to 2022 and this is still the case.